Max Aub died three years before Francisco Franco, but he was the first to imagine the dictator’s end and put it in writing. He killed it brilliantly and soon enough. 15 years before the dictator died in La Paz hospital, Madrid, on November 20, 1975, was published in 1960 in Mexico The true story of Francisco Franco’s death. That story by Max Aub (Paris, 1903-Mexico City, 1972) will officially arrive in Spanish bookstores until 1979, published by Seix Barral. At that point the transition was already underway and the Constitution had already been approved.

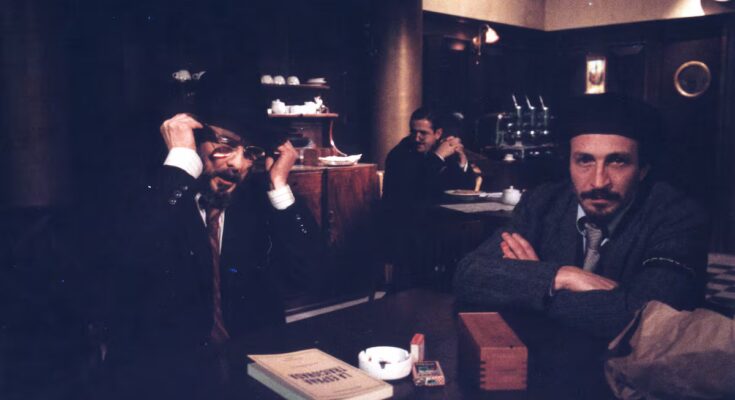

Previously, the publication of the story on Libros Mex had raised the alarm bells of the Francoist authorities who not only censored its diffusion, but also prohibited any mention of the title, in case it gave any idea, and the author was denied a visa. Aub finally managed to visit Spain in 1969, and would emerge from that trip The blind man’s hen, Spanish newspaper. And if in that book he glimpsed the future transition with skepticism and expressed his discomfort for the country he found, in his 1960 story he put his finger on that “biological fact” that the regime persisted in denying. In his account, the dictator did not die in a hospital bed while doctors tried to keep him alive and underwent subsequent operations, but rather fell without too much trouble during an attack. The perpetrator of the assassination is Ignacio Jurado Martínez, originally from Sonora, Mexico, a waiter in a bar in Mexico City where Spanish exiles meet every day, who embitter their passion for work with their incessant talk about the war and Franco. Jurado Martínez’s motivations are more personal than political: he hatches the plan to kill Franco and asks for the only vacation he’s ever taken in his life to shoot him and see if he can get rid of those clientele. Because in the end, The true story of Francisco Franco’s death It is an acid portrait of the world of exile, a uchronia which, as happens with the best fiction, returns a precise and accurate image that would be difficult to tell without the resource of imagination. Franco’s death in this and other fictions tells more about the rest than about the dictator himself. There he is Mr. Cayo’s disputed vote (1978) by Miguel Delibes, which alludes to the end of the dictator starting from the incipient democracy.

Several generations of Spaniards remember where they were when they received the news of his death, on November 20, 1975. The anniversary remains one of those indelible dates and, however, its imprint in literature and its narrative potential in Spanish fiction is not so evident. There are many essays, biographies and history books, fewer novels. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and his men Autobiography of General Franco (1992) or Francomoribundia (2003) by Juan Luis Cebrián are part of a strange list. It stands out in a unique way The fall of Madrid (2000) by Rafael Chirbes, a novel that takes place in the uncertainty of November 19, 1975, and in which half a dozen characters intersect (from a commissioner to a student, to a professor in exile and a worker). Chirbes talks about others while the dictator dies, this is the axis of a choral story.

The truth is that Franco’s death is in most cases a tangential event in the novels written in that period and also in subsequent novels. It arises here and there. One of the characters of Tomorrow, by Ignacio Martínez de Pisón, calls the police station and discovers that Franco is dead. The narrator of The back roomwritten by Carmen Martín Gaite from 1975 to 1978, confesses to his mysterious interlocutor that he had invented a book on the customs and loves of the Franco regime when he saw the funeral on television: “After Franco’s death you will have noticed how memoir books proliferate, it is already a plague, after all, it is what discourages me, thinking that if other people’s memories bore me, why don’t they go away? boring others with mine. And between those memories of the moment and further back there are those (not at all boring) by Jorge Semprún Autobiography of Federico Sánchez (1977) recalls how, having heard the news that the end of the dictator was near, he returned to Max Aub’s book and stopped at the dedication: “‘Let’s see if…’, Max had written at the beginning of the Sixties. Let’s see if what he had imagined in the story happens, or something similar, let’s see if the false story of Francisco Franco’s death becomes true.” And then he concludes, after organizing his trip to Madrid: “We would all have been spectators, passive spectators, of the end of a regime that had been impossible for us to overthrow.”