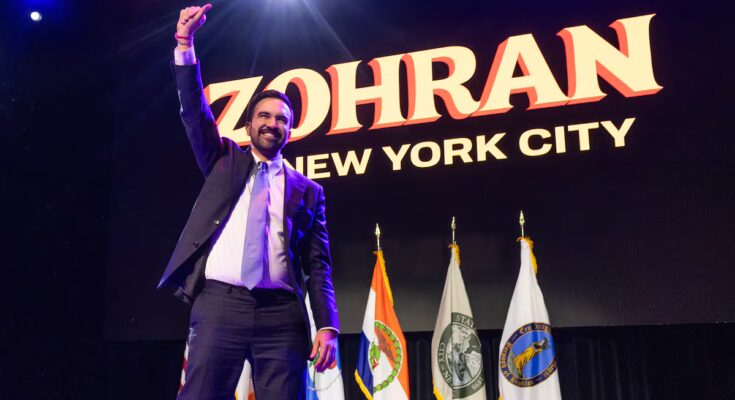

Democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani’s resounding victory in the New York mayoral election is the Democratic Party’s most significant achievement this election cycle. His broad coalition – spanning class, race and every district except Staten Island – gave him a decisive victory in the country’s most populous city and made him the most visible Democratic leader in the United States. However, his rise also highlights a profound paradox within the party: its most powerful and electorally successful figure is constitutionally barred from seeking the presidency.

Mamdani was born in Uganda, so he is not a natural-born American citizen, as required by Article II of the Constitution to be president. That single circumstance marks the limit of his political destiny: no matter how much popularity he achieves or how much accomplishment he accumulates, his career stops at the door of the White House. He could be re-elected mayor in 2029 – New York law requires two consecutive terms – or later aspire to become governor or senator, but not being able to even try to occupy 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue will be a characteristic that will inevitably define his career.

In his rise, Mamdani has so far collected several “firsts”: he is the youngest mayor since the creation of “Greater New York” in 1898, the first of South Asian origins and the first Muslim to govern the city. However, New York’s political history is unforgiving. No mayor has made it to governor since John T. Hoffman in 1869, no one has made it to Congress since Adolph L. Kline in 1921, and no one has made it to the presidency, although many have tried: most recently Bill de Blasio, Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg. Perhaps, more than a paradox, Mamdani’s fate is simply another chapter in the old “curse” of New York mayors, condemned to shine in the Big Apple, but unable to project their own light beyond it.

However, his 34 years will allow him to exert a lot of influence and, if he plays his cards right, he could become a definitive voice within the Democratic Party for decades, with the strength that not being a competitor of other figures in his party for the presidency would give him.

The party’s situation is even more revealing when analyzing the Democratic performance in the November 5 elections outside New York. In addition to Mamdani’s victory, the party achieved numerous important advances, including the passage of Proposition 50 in California, a measure that strengthens California’s ability to redraw the distribution of its electoral districts, the so-called gerrymandering– which could translate into more seats and even an eventual Democratic majority in the House of Representatives in Washington ahead of the 2026 midterm elections.

The electoral reconfiguration power of Proposition 50 consolidates California as a political counterweight to Washington and as a key tool for maintaining and even expanding Democratic influence on the national stage; The measure was a direct response to Republicans’ strategy in states like Texas, where they also used the gerrymandering to guarantee their majority.

However, measuring the state of the Democratic Party by what happened in California and New York is a biased reading. Both states, including the Big Apple, have Democratic majorities and do not reflect the sentiment of the country as a whole. At the national level, the party lacks clear direction and truly innovative proposals. From representing the working classes and minorities in the past, it is now seen as a force dominated by intellectual elites with claims to moral superiority which, while sympathetic to minorities, has little connection to the daily lives of ordinary people.

The space of emotional closeness with the average voter has been occupied, at least for now, by the Republican Party and more directly by Trumpism. It is not for nothing that Trump won, just a year ago, the presidency of 31 of the 50 states of the Union, including the seven oscillating states (or pendulum states), who would have obtained 312 of the 538 electoral college votes – 58% – and that his party now controls both houses of Congress.

It remains to be seen, then, whether the Democratic Party will be able to capture and transfer to a national scale the bond that Mamdani has established with New York voters. To do so, he will have to adapt his message to an audience less liberal than New York and reconnect with the average American. The party’s great challenge will be to convert that local energy into a national narrative to, without condescension and with a clear national leadership that does not exist today, speak to the common citizen again.

A survey published by Political last week among Democratic voters, shows how widespread that party’s leadership is: 21% of respondents said they didn’t know who led the party. 16.1% responded that it was Kamala Harris, former vice president and former presidential candidate, while 10.5% responded that “no one.” The remaining 52.4% is distributed among 26 people, with Mamdani currently very low at 0.3% and, curiously, Republican Donald Trump at 0.8%.

The contrast is clear: while candidates and democratic initiatives have had good results at the local level, the party still lacks a national voice or figure capable of unifying its message. Mamdani’s prominence, however impressive, only highlights that void. Today he is the best-known Democratic politician in the country, but he will not be able to transform his electoral strength into presidential leadership.

This year’s elections have revealed both the potential and the limits of democratic renewal: a party with energy at its base, victories in some important cities and states, but still without a national leader to unite it or a message that speaks to the real country.

Next year’s legislative elections will demonstrate whether Democrats have learned anything from this cycle or whether – as so far – they will continue to watch the bulls from the sidelines.