The word, even the word of God, must sometimes be an image in order to be better understood by humans. This happens with cycles of frescoes dedicated to the lives of prophets, Christ or saints; and this is what the centuries-old examples of the Biblia pauperum, the Bibles of the poor, which presented pictures with episodes from the ancient history of Israel and the Gospels for the use of the illiterate, or the illustrated and illuminated Bibles which in the Middle Ages – with a tradition born in France at the end of the 12th century and then arriving in Italy – had rulers, princes, high church officials and rich nobles commissioning the best artists and craftsmen for their own pleasure.

And among the illustrated Bibles, which with short texts and many pictures summarize the sacred story scene by scene, there is one that is considered the most beautiful and valuable, unique in the world, having enormous value from a historical, artistic and bibliophile point of view. This is the historical Bible of Padua. Built in the last decades of the fourteenth century and commissioned by the Da Carrara family – when Padua, Urbs picta, was as populous as Paris, when between the University and the library of the Basilica del Santo, the city had a book heritage incomparable with most other Italian cities, when it was host to Francesco Petrarca and when the eyes of all citizens shared the visual image of Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel and Giusto de’ Menabuoi’s paintings in the Baptistery – the Bible consists of a magnificent manuscript illuminated with 873 “sketches” cut into two parts, probably in the 16th or 17th century. Which through a thousand changes arrived, one at the Accademia dei Concordi Library in Rovigo and the other at the British Library in London, where we saw it in September. The first, the one from Rovigo, contains the Biblical incipit Genesis, as well as the Book of Ruth: there are 24 leaves and 344 cartoons; the second, which is in English, reports the middle sections of the Pentateuch (Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy) and the Book of Joshua: 86 picture cards, decorated with 529 illuminated images. Other books may exist, but no one knows where they end up.

Today both halves of that extraordinary volume are reunited for a major exhibition in the city where it all began, Padua: entitled The Padua Historiated Bible. The city and its frescoes were recently unveiled in the Great Hall of the Diocesan Museum (until April 19, 2026). Curated by Alessia Vedova with the scientific collaboration of Federica Toniolo and promoted by the Cariparo Foundation, which has secured the important collaboration of the two institutions that guard the Bible, the exhibition allows you to admire two parts separated by centuries side by side and, in an immersive space, revive the historical and artistic – now we could say intellectual – environment of fourteenth-century Padua, while on the Veranda of the Diocesan Palace the pages of the Bible “flow” in facsimile, so as to follow the development of the story illustrated.

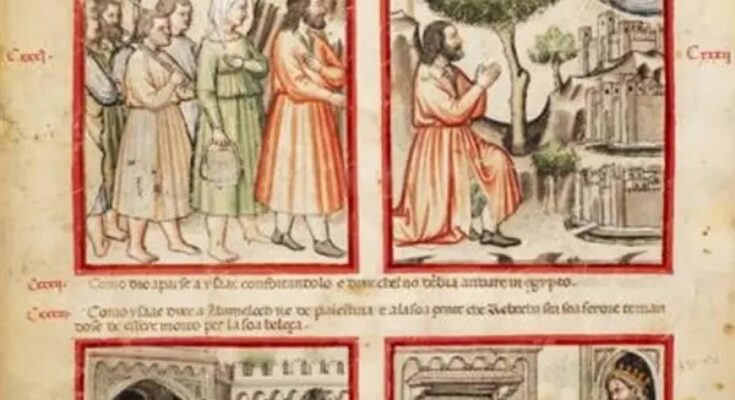

Made on very expensive parchment by highly experienced illuminators (it is thought that the hands belonged to three artists: a famous workshop was active in Padua) who first drew with pencil or graphite and then applied colors in tempera and finally gold paper, and by amanuensis for written work, the historical Bible – already renamed the “Comic Bible”, a kind of graphic novel ante littram – clearly prioritized the narrative element over the theological one. It is a summary of the biblical story through a series of miniatures (i.e. square cartoons, inside red frames, usually four per page) that give strength to the text. The pictures are like photographs of fourteenth-century Padua: the clothes, the tools (which were used, for example, Noah’s Ark to build), the materials and the architecture are those of the craftsmen and the buildings of the city of that time (even the fireplace is the “tower” of Monselice…); just as the characters come not from biblical history, but from medieval Padua, namely urban and rural figures. “There are banks, wedding ceremonies, ways of cultivating the land”, explains Federica Toniolo, medieval art historian and scientific coordinator of the exhibition. And the language of the text is not Latin, as in all previous Bible illustrations, but vulgar Italian with Venetian inflections, in an era when Florentine was not yet the literary language of the Peninsula, didascally summarizing Old Testament episodes: in fact it is not uncommon to read references to “Como qui si è pento”.

The historic Bible, the product of a secular client (most likely commissioned by Francesco Novello da Carrara), is not a sacred text, but a representative work of art, an artifact of extraordinary delicacy that certainly bears witness to the wealth and fame of Carraresi, Lord of the city and great patron.

“But this is a book that at the same time also shows the close relationship between faith and culture – said Don Lorenzo Celli, vicar bishop of Padua –. Without faith, such masterpieces would not have been created, but without culture the word would not have been revealed”.