The deadliest avian influenza virus in history, responsible for the deaths of hundreds of millions of birds over the past five years, has once again jumped to mammals and devastated the world’s largest elephant seal population, located on the remote South Georgia Island, a territory under the control of the United Kingdom and located about 1,500 kilometers from mainland Antarctica. The British Antarctic Service estimates that more than 50,000 females – half of the total – have disappeared from one year to the next. “The magnitude of this decline is shocking,” warns marine ecologist Connor Bamford, leader of the research.

The virus’ journey began in 1996 on a goose farm in Sanshui, southern China, a humid region plagued by poultry farms: the perfect breeding ground for the emergence of new pathogens. After several waves of lesser intensity, a new version of the virus emerged in 2020, called 2.3.4.4b, and began traveling across America from north to south, with a lethality never seen before. According to data from the World Organization for Animal Health, highly pathogenic avian influenza killed or forcibly killed nearly 150 million birds in 84 countries in 2022 alone. On September 16, 2023, a group of British scientists came across a specimen of the Antarctic giant petrel – a bird with a two-meter wingspan – that was unable to move, on Bird Island, near South Georgia. The plague was just arrived at the gates of Antarctica, the last virgin continent on the planet.

There the virus quickly spread among mammals. Connor Bamford’s team used drones to count female elephant seals in South Georgia’s three main colonies. Before the avian flu epidemic there were around 10,000 of them. After the virus arrived, almost half disappeared. If the results are extrapolated to the entire population of the island, there are 53,000 fewer females, a huge blow for the southern elephant seal, a species until now considered out of danger. Two decades ago, according to the last population census, there were around 700,000 specimens in the world.

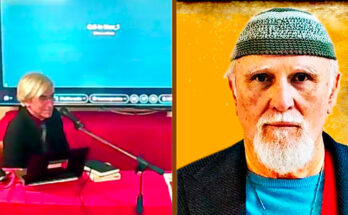

Spanish virologist Antonio Alcamí led two expeditions in 2024 and 2025 to try to measure the impact of avian influenza in Antarctica. Aboard a sailboat converted into a laboratory, scientists earlier this year explored the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, the region of that continent closest to South America. The virus was already everywhere, in practically all places visited and in one in four animals analyzed. The penguins proved more resistant than feared, but the pathogen preyed on other birds, such as Skuas. Two journalists from EL PAÍS documented the ravages of avian influenza in Antarctica for the first time, accompanying the Spanish expedition.

“Just because we don’t see marine mammal corpses doesn’t mean they aren’t dying, because maybe they are dying at sea, where we don’t see them,” Alcamí argued at the time, on the deck of his sailboat in dangerous Antarctic waters. Now, he warns that the decrease in the number of females by half in a single year “is a very high figure”, especially in a species where individuals, weighing up to four tons, can live more than 20 years under normal conditions. “This is a huge impact, especially if we consider that 50% of its breeding population is located in South Georgia,” warns the virologist from the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC). The new work is published this Thursday in the specialized journal Communications biology.

Alcamí denounces the lack of support for analyzing the effects of avian influenza in Antarctica. “There is concern that the impact on other marine mammal species may be similar, but we simply have no information about what is happening,” he laments. Its mission last year was possible thanks to a donation of 300,000 euros from the Spanish Union of Insurers and Reinsurers, in addition to the logistical support of the CSIC Antarctic base, financially supported by the Ministry of Science. This year he is unable to find funding to continue his research. “It’s a little frustrating,” he says.

Veterinarian Ralph Vanstreels, the son of a Spanish woman and a Belgian man, witnessed the most harrowing scene of his career in October 2023, on a beach on the Valdés Peninsula, a protected area in Argentine Patagonia. The sand was so covered with dying or dead elephant seals that it was difficult to walk. He and his colleagues estimated that the virus killed about 17,000 individuals in just a few weeks, including more than 95% of their offspring. “The new study conducted in South Georgia is very alarming, because it indicates a very similar pattern to what happened here in Argentina. It suggests that all elephant seal populations where the virus has already caused epidemics could be affected at the same level. It is very serious,” reflects Vanstreels, of the University of California at Davis (USA). “It’s a species that wasn’t threatened and, all of a sudden, it was reduced by half. This has very serious implications for the conservation of the species,” he points out.

Analysis of the epidemic in Argentina highlighted a disturbing possibility: the virus not only jumped from birds, but was then transmitted from elephant seal to elephant seal. The evolution of such a contagious and deadly avian influenza virus in mammalian populations is the scenario most feared by public health experts, as the scientific director of the World Health Organization, the British doctor Jeremy Farrar, warned after an epidemic of avian influenza on a mink farm in Galicia in October 2022. The institution, however, believes that the risk for people is “low”, unless the virus mutates and begins to spread among animals. humans.

Ecologist Connor Bamford points out that the pathogen is still present in elephant seal populations. His colleagues are reading the genetic material of the virus from different animals, to try to discover what its journey across the island was and what mutations it had along the way. “There was mammal-to-mammal, airborne transmission, with contaminated droplets transmitting the virus between hosts. This is probably why elephant seals, which form dense colonies in South Georgia every year, were so severely affected,” says the researcher from the British Antarctic Service. Bamford acknowledges that other factors may have contributed to the disappearance of females, such as some local climate anomalies, but points out that natural variations from one year to the next can be at most 10%, never 50%. “Decreases like the one we observed can only be attributed to highly pathogenic avian influenza,” he says.

Elephant seals are divided into two species, the majority in the south and the minority in the northern hemisphere, currently little affected by the virus. Biologist Michelle Wille manages the avian influenza database of the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research, the international body that coordinates Antarctic science. “Highly pathogenic avian influenza has been catastrophic for southern elephant seals,” he says. “These mortality rates are shocking, but not surprising, because we have seen similar numbers in numerous bird species. The implications are considerable,” continues Wille, of the University of Melbourne, Australia. “You wonder if this species will survive this.”