Few scientific questions raise as much dust as the origins of autism. Science knows it has a genetic basis, but the exact causes are unknown. And as he continues to search for answers, bizarre ideas and recurring hoaxes emerge. Like that fraudulent article by British doctor Andrew Wakefield in which he pointed out, 25 years ago, that vaccines cause this neurodevelopmental disorder. Or Donald Trump’s recent announcement linking, without any type of scientific proof, the origin of this pathology with the intake of paracetamol during pregnancy.

Serious scientific research and the most plausible hypotheses also find their place in the hubbub of charlatans. Even if the debate is not closed and not even there, in the academic field, it seems that all that glitters is gold. An investigation published this Thursday in the magazine Neuronof the Cell Press group, put his finger on the sore point of science and denied one of the most popular and apparently well-founded hypotheses on the possible causes of autism: the one that linked the intestinal microbiome to the origin of this disorder. The research identified “serious shortcomings, inconsistencies and contradictions” in studies supporting the theory that autism is caused by alterations in the ecosystem of microbes that populate the gut.

The authors believe that this thesis has reached a dead end and warn against the temptation to simplify a condition whose origin and development are much more complex than all this.

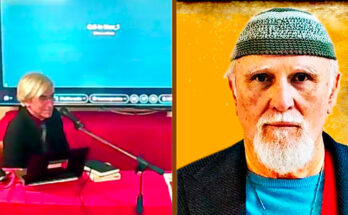

Kevin Mitchell, a developmental neurobiologist at Trinity College Dublin and first author of the study, says that “there is a kind of strange mystique around autism that doesn’t seem to apply to other neurodevelopmental conditions.” He doesn’t know where it came from, he admits, but he believes what’s really driving the proliferation of speculative theories about this disorder today is the increase in diagnoses: The global prevalence has gone from 773 cases per 100,000 population in 1990 to 788 in 2021. “This seems to require an explanation, some environmental factor that must be causing this increase.”

In fact, he points out, there is “clear evidence” that this increase is due to changes in diagnostic practices – greater precision in case finding – and “not a real increase in the underlying condition”. But with the decontextualized numbers on the table, the high prevalence of gastrointestinal problems in people with autism, and growing social interest around this disorder, it sets the stage for the most simplistic conjectures.

And it is there, in that context, that the hypothesis of the causal link between the microbiome and autism gains strength: every year dozens of articles are published that explore this thesis in depth and this scientific interest has also permeated public opinion. But Mitchell and his colleagues admit that there is a “concern” among many scientists that perhaps these theories have spread too quickly and their credibility has outweighed the hard evidence supporting them.

The approach is attractive from the start, he admits: “The whole idea that gut bacteria can influence our mind is truly radical. It seems to open up a completely new and unknown field of biology, revolutionize our conception of how psychology works and even redefine our identity as people. Therefore, it is natural that it has attracted so much interest.”

And in the case of its link to autism, he adds, the microbiome “appears to offer an identifiable cause and a possible avenue for treatment.” It is a simple, concrete theory that is easy to explain in a field, such as that of neurodevelopmental disorders, where a tangle of complex variables and many unanswered questions have always converged. “It is attractive for its simplicity (despite the vagueness): this incredibly complex condition can be explained by something in the gut,” Mitchell says in an email response to EL PAÍS.

“No concrete evidence”

The problem with all this is that reality is stubborn, and the temptation to simplify complex conditions easily disintegrates when you look at the fine print of the grandest theories. This is demonstrated by Mitchell’s work and a study recently published in the journal Natureelite of world science: this research confirmed that there are genetic differences in autism depending on the age of diagnosis and suggested that talking about “a single cause” or “an epidemic” does not make sense, since there would be several subgroups differing in origin and evolution.

As for the microbiome’s causal role in all of this, in their study, Mitchell and his colleagues analyze the strength of the evidence and find flaws and setbacks in all phases of the research, from mouse studies to human trials. “We conclude that there is no concrete evidence to support the hypothesized causal relationship between autism and the microbiome,” they conclude bluntly.

In observational or epidemiological studies, which look for – and presumably find – differences in the microbiome of people with and without autism, the authors propose that these are investigations with few participants, the data are “imprecise,” and the results between studies are “inconsistent” or even contradictory.

If anything, they point out, if any association exists, it is probably due to “reverse causality”. That is, this alteration of the microbiome is a consequence of the disorder – autism can affect the diet and this, in turn, the microbial composition – and not a cause.

The mouse studies also show “methodological shortcomings” and the results are “highly questionable,” Mitchell notes. And in human clinical trials, in which the microbiome is manipulated with fecal transplant or probiotics, there appear to be inconsistent conclusions, in the authors’ opinion. “Although some studies have claimed improvement in symptoms, they tend to be small, open-label studies without a control group,” notes Mitchell. There is no evidence that these interventions have a beneficial effect, they conclude.

“The impression is that the literature is not cumulative, with subsequent studies replicating and building on previous ones; rather, the logic of a study is that ‘something is happening’ in relation to autism and the gut microbiome, and each study adopts different methods without consistent and replicable findings emerging,” the authors say in their review.

The contradictions and shortcomings are of such magnitude that the authors even propose abandoning research in this field: “I do not believe it is justified to dedicate more time and resources to this topic. We know that autism is a condition with a strong genetic component and there is still much to be investigated”, underlines Mitchell in the statement. A view shared by lead author and developmental neuropsychologist Dorothy Bishop of the University of Oxford: “If you accept our message, there are two paths. One is to simply stop researching in this area, which we would be very happy to do. But given that the research is not going to be abandoned, we need to at least start conducting these studies in a much more rigorous way.”

The danger of “hasty interpretations”

Neus Elias, psychiatrist at the Multidisciplinary Unit for Autism Spectrum Disorders of the Sant Joan de Déu Children’s Hospital in Barcelona, admits his surprise at the “strength” of the authors in exposing their rejection of this theory, but agrees with the conclusions and assures that an internal review carried out by his team reached the same conclusion: “This is what we explained to the families. This article states that causality is not proven. There they are evidence that something is happening, but perhaps there are other explanations. And it is one thing to talk about causality and another to talk about risk factors that can influence the evolution of autism.”

As a backdrop to this controversy – and others raised by autism – there are also powerful economic interests behind it, experts agree. Toni Gabaldón, head of the Comparative Genomics group at the Institute of Biomedical Research (IRB Barcelona), in statements to the Science Media Center portal, states that he “partially” shares the authors’ vision and that the press and industry could treat the results in this field “in an exaggerated way”. “This type of hasty interpretations can be exploited by the nutraceutical or probiotic industry to sell products with unproven efficacy, which can generate false hopes. Today there is concrete evidence of correlations between intestinal alterations and autism, but the evidence of causality remains hypothetical and difficult to demonstrate”, he underlines, although he believes “it is essential to continue investigating possible causal links” in this field.

What all the voices consulted agree on is that autism is an extremely complex condition and looking for simple explanations makes no sense. The authors argue that genetics “has only just scratched the surface” of its role in autism and many genetic variables remain to be discovered. “Researchers have identified dozens of risk genes for autism, and more continue to be identified regularly. The problem is that the genetics of autism are very complex and their understanding is still developing. This makes it very difficult to communicate progress to the general public and leaves a void that more speculative (but simpler) theories will fill,” Mitchell predicts.