In 1898, as Spain lost Cuba, two British scientists discovered neon gas. In a London laboratory, William Ramsay and Moris Travers discovered to their amazement that if they stored this gas in a glass tube and allowed an electric current to pass through it, it emitted an intense, vibrant red light that seemed to have no end. But little more than a decade had to pass before the commercial debut of this discovery. And it was not them but Georges Claude; This French engineer presented the first neon lamp during the 1910 Paris Motor Show. Claude’s design consisted of sealed glass tubes containing neon, an inert gas present in the atmosphere in small quantities. The popularity of neon lights skyrocketed and flooded the streets of the French capital in the 1920s. The fashion for illuminated signs in Pigalle and the Champs-Elysées immediately crossed the ocean. In 1923, a Los Angeles businessman had neon signs brought in from France to illuminate his car dealership and marked a point of no return. That “liquid fire” quickly spread through the streets of New York, Las Vegas and the large urban centers of the planet to become one of the emblems of 20th century modernity.

When he was a teenager, Leoncio Villoro (Barcelona, 87 years old) told his father – an electrician – that he no longer wanted to study. Do you want to work? Then get to work! The next day he began his apprenticeship in the workshop in Lisbon, dedicated to signs. “Well, I was the delivery boy: go get the water, go get the wine… And so I spent three years without earning a penny. But I paid a lot of attention to everything they did. They didn’t teach me, I learned”, recalls Villoro, who finished his training in the workshop of Castro Núñez, one of the first to bring neon lights to Spain after a trip to the United States. Although Villoro has already been retired for years, until four days ago he was still helping his son in his workshop in the Sant Martí de Provençals neighborhood of Barcelona, on whose door there is a very eloquent sign: Luminosos Villoro. “After working for others, I finally set up my own business and in 1970 we moved to this location,” he says. Half a century later he is still there, but his son Leo Villoro (Barcelona, 47 years old) is in charge. “He came out like me, he wasn’t a very good student,” his father jokes. “But he grew up here. He liked the work and learned quickly. Now he’s better than me. Look at him, look at him,” he says proudly.

On an old wooden table, Villoro Jr. easily manipulates a greenish glass tube. “They are the remains of a lot that we purchased many years ago,” he explains. Thanks to a small blowtorch, that rigidity takes the shape that was previously drawn on paper. “He’s making a lamp in the shape of a cactus. In 1975 I saw a western film and a lamp like this appeared. I took a pencil, drew it and we haven’t stopped making it since then”, explains the father. With the exception of this cactus and a pink flamingo, Luminosos Villoro does not produce its own produce. They always work to order. For decades, the bulk of the business was commercial signage, which at its peak was distributed across seven workshops in Barcelona. Today only two remain and the technique – 100% handmade – remains almost the same as a century ago. “The big difference is that now the glass is pyrex,” exclaims Villoro Sr. “Before we had difficulties with soft glass, we had to be very precise!”

Roadside bars, restaurants, hotels, haberdashers, nightclubs, pharmacies, property management, perfumeries, record shops… In the Seventies, Eighties and even Nineties, Barcelona and any other European city would have had its own neon street. Today many signs have been lost and, among those that remain, the most emblematic are protected as historical heritage. “We are also dedicated to their repair. Although they last a long time, a knock or breakage can be fatal because they cause a gas leak and stop working,” explains Villoro Jr.

For this reason, in recent times those who want a neon sign have switched to the LED version, which is also cheaper. «But it’s not the same thing, it’s not the same thing», mutters Villoro senior. And he is absolutely right: they do not have the soul of “liquid fire”, because obviously they do not contain any gas: neither neon, nor argon, nor xenon, the triad most used for lighting. Despite the emergence of LED, a hymn to nostalgia neon – started about 15 years ago in London – has once again saved the taste for authentic neon lights. Therefore, the new premises have once again opted for this retro aesthetic. In Barcelona many of them have passed through the hands of the Villoro family, from Casa Bonay’s Libertine cocktail bar to the La Porca burger joint. And orders, fortunately, continue to arrive at Luminosos Villoro. Last? A new restaurant opening in Marseille.

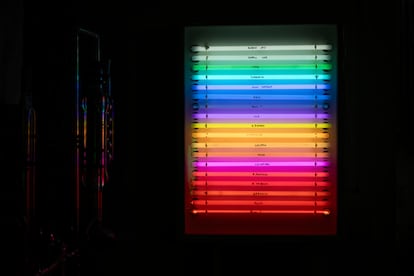

As we speak, Villoro Jr. has already given shape to the cactus. Next, place the electrodes on each of the two ends. Now comes the most delicate part: remove the air inside the glass tube with a vacuum pump and then introduce the gas at low pressure. If this operation is not done correctly, the cactus lamp will not light up when it comes into contact with electric current. But it does, and it gives off a very intense green light. In this work the theme of colors is a whole world. Villoro Jr. points to a panel on the wall. There are a dozen samples of glass tubes illuminated and labeled according to their hue: France red, purple red, pink, salmon, banana yellow, deep blue, turquoise, green, white… It’s your particular Pantone.

The coloring of the glass tubes, coming from the factory, is obtained thanks to matches which, mixed with the injected gas, allow a range of colors to be created. “It’s like a game: if I inject neon gas into a green tube, I get an orange hue. If I inject argon gas instead, like I just did with the cactus, this intense green color appears. If the tube were colored blue and I inject neon gas, the color that would appear would be Pink France,” he explains.

In the history of neon lights, but also of art, the year 1951 was crucial. The Argentine artist of Italian origins Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) participated in the IX Triennale of Milan with the installation Space light. Nothing more and nothing less than a huge neon tube suspended from the ceiling which gave light the possibility of configuring the space. With this work, Fontana opened a door that was later crossed by other artists who consolidated light tubes – be they gas neon or commercial fluorescent tubes – as a creative material. Here’s how light art. But six years before Fontana, in Buenos Aires, Gyula Kosice had already created abstract sculptures with neon lights, a line of experimentation that would continue throughout his life.

After them, in the 1960s and 1970s, Bruce Nauman, Mario Merz, Keith Sonnier and Joseph Kosuth consolidated neon lights as their own language, integrating them into various artistic movements such as conceptual art, postminimalism and arte povera. A trend which, with its ups and downs, has continued to the present day, with relevant names such as Jeppe Hein, whose installation Please (2008) is part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, to name just one example.

“Our clientele has changed a lot. We have been working for museums and art galleries for a long time. In my father’s time we were mainly sign manufacturers,” explains Villoro Jr. Something similar happened with Rudi Stern, who opened a studio in New York in the 1970s and specialized in building neon lights for Broadway shows. Over time, he ended up collaborating with artists such as Jeff Koons, Keith Haring and Robert Rauschenberg. “We also collaborate with artists: Samuel de Sagas, Pedro Torres, Enrique Baeza… The last one was Marria Pratts. Some come and want to learn to do it themselves, but they quickly realize that this is a craft, that it takes many years of practice, very specific machinery and that it is better to leave it in our hands,” he says.

In fact, he himself is a kind of eternal student. “When I plan my holiday I always reserve a few days to visit it neon lights and see how they work. I contact them on Instagram and they are always happy to welcome me to their workshops. In August I was in Hong Kong and visited someone who still works with soft glass. It was fantastic! I invited you to come to Barcelona and see how we work with Pyrex. On another trip to New York, I visited Rudi Stern’s space, now run by his partner. And you see that sign that says No Vacancies? It was given to me by A neon that I found myself doing Route 66. We immediately recognized each other. “We’re like a cult,” he jokes, and father and son laugh in unison, as they have for many years in this same laboratory.