But what kind of authoritarian reform? But which fascism? Career separation has been called for, for decades, by a broad and transversal group, with roots deeply embedded in the left, namely socialists, radicals and liberals (maybe not communists, huh). And it touches the Democratic Party.

It was always a misleading and insincere reflection that led to attributing a “fascist” character to the intentions of the “right-wing” coalition, and this government in particular, but in the case of “fair justice”, a fair trial, or the reforms that the Italian people will ask to be confirmed (or not) by a referendum vote, the ideological scheme becomes a total mystification, even if today – in the current ideological clash – it is no longer clear where the repression ends “in good faith” and where the falsification begins.

But this narrative – made up – has become an obsessive one that claims that the center-right is planning to subordinate investigative agencies to the executive branch. And the argument that the reform would be a “plan” to “empty out” representative democracy is completely arbitrary, as “Democratic Justice” president Silvia Albano told L’Unità. There are even those who try to compare – a topic present in the “No” campaign and popular among Chancellor Tomaso Montanari – the modification of the Constitution voted for by Parliament and the democratic rebirth plan”, a subversive project by Licio Gelli. A propaganda trick that is not only childish, as explained in his column in “Radio Radicale” by Gian Domenico Caiazza, former president of the Union of Criminal Chambers and now leader of one of the “Yes” committees, but also baseless. A “sensational fake news” according to the lawyer, because the plan “has nothing to do with current reforms”.

And if many exponents of the democratic left, guarantors, and reformers are (and have been) on the side of judicial reform (including code father Giuliano Vassalli as well as Elly Schlein’s grandfather, senator Agostino Viviani), the idea of a “fair trial” can also be clearly theorized in the pages of Giacomo Matteotti.

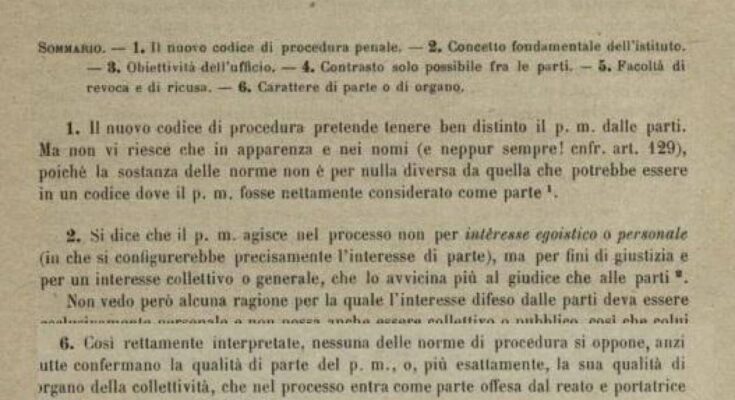

A socialist, even before becoming a violent opponent and victim of fascism, Matteotti was a fine jurist. And in 1919, in what Giovanni Canzio defined as a “short and libelous” essay, the reformist lawyer laid out his vision of the public prosecutor in a piece published in the Penal Review, an essay eloquently titled “The public prosecutor is a party.”

In open disagreement with the idea that the prosecutor is above the parties, Matteotti clearly outlined the idea of a trial in which the parties are on an equal footing before a third judge. “The division of powers that underlies modern constitutional regimes and the division of functions – observe – allow for the manifest absurdity of a State being judge and party at the same time”. Looks. “There are no rules of criminal procedure – concluded Matteotti – that are contradictory, in fact all of them emphasize the role of the prosecutor, or more precisely, its role as a public institution, which enters the trial as a party injured by a crime and the perpetrator of a criminal act.”

It would of course be wrong to draw current conclusions from this three-page 1919 essay, and anyone can draw the conclusions they find most convincing, but it is impressive to note how, ten years later, fascism in power would reverse this point.

adheres to the idea of a State which, by overcoming the division of powers typical of liberal institutions, also overcomes the separation between the judiciary which adjudicates, which is subordinate to the executive, and the judiciary which adjudicates.