With Franco’s death, the anger did not end. Forty years is an eternity: on November 20, 1975, many Spaniards had only known Francoism and almost considered that that dark regime of scoundrels, louts and meapilas was, more than a dictatorship, the natural state of things. This explains why the most widespread feeling in Spain on the day of Franco’s death was neither joy nor sadness; The most widespread feeling was uncertainty, perplexity and restlessness. No one captured it better than Julio Cerón, that unique diplomat who founded the FLP (Popular Liberation Front) in the late 1950s and paid for his anti-Franco audacity with about three years in prison. “When Franco died, there was great confusion,” he said. “There wasn’t any custom.”

There are those who think that democracy in Spain was inevitable after Franco’s death; Surprisingly, some protagonists of that period also thought so. It is a teleological mirage. Democracy is not a gift but an achievement, therefore it is never inevitable, much less in that sudden Spain without Franco; Indeed, some prominent political scientists, such as Giovanni Sartori, thought at that time that we Spaniards were not prepared for democracy. Our Government’s celebratory motto – “Spain in freedom. 50 years” – contains a flagrant falsehood. Franco’s death did not represent the end of Francoism; nor the principle of democracy. Francoism was robust at Franco’s death, although not robust enough to prevail over anti-Francoism; Anti-Francoism was strong after Franco’s death, although not strong enough to prevail over Francoism. Democracy emerged in Spain from this bond of impotence.

But it didn’t arrive right away. What Franco’s death brought was not freedom: it was the beginning of a series of political and social movements that would later be known as the Transition, and which ultimately brought about the transition from a dictatorship to a democracy. That historical period has become politically controversial, not because our politicians have any real interest in history, but because even the dumbest politician knows that to control the present and the future, he must first control the past. This elementary Orwellian wisdom is responsible for the fact that, since the party system generated by the Transition disintegrated or seemed to disintegrate in the middle of the last decade, it entered the political battlefield: the new parties needed to impose a version of the past useful to their interests, manipulating or falsifying it at will to delegitimize their opponents, who they rightly held responsible for this. The result was the emergence in the public debate of a double and contradictory history of the Transition, which until then had remained buried, in germ.

Result of that result: Right now there is a pink version and a black version of the Transition. The pink version, supported by the right and many protagonists of the era eager to claim their own execution, postulates that the Transition was a period of perfect harmony between exemplary elites, whose unyielding common sense and historical sense favored a peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy; Supported by the far left and secessionists, the black version claims that the transition was an ignominious rinse thanks to which the regime par excellence – Francoism – was transmuted into the regime of ’78, which in essence is not an authentic democracy but a false democracy: Francoism by other means. I don’t know if it is necessary to add that both versions are false. The truth is that, as all the indices of democratic quality in the world demonstrate, the Transition has given rise to a true democracy, worse than some and better than many, imperfect like all; It also illuminated – it’s not an opinion: it’s a fact – the best fifty years of modern Spain. It is no less true, however, that that was a very complex period, saturated with ethical chiaroscuro, political balances, social tensions and violence from the right and the left, and that, if from mid-1976 to the end of 1978 political agreement, historical responsibility and the will to escape from dictatorship and build a democracy dominated the ruling class, from the beginning of 1979, once the Constitution was approved, political life experienced an unprecedented discord. barracks, extreme polarization and, at times, suicidal irresponsibility, which ended up leading to a coup two years later.

That was the key moment. Legally, democracy began on December 27, 1978, when the Constitution was promulgated after having been approved in a referendum three weeks earlier; symbolically – that is, in reality – it began at half past six in the afternoon of February 23, 1981, in the hall of the Congress of Deputies, when the three most decisive politicians for the establishment of democracy, who had not believed in it for most of their lives – Adolfo Suárez, General Gutiérrez Mellado, Santiago Carrillo – decided to risk their lives for democracy. Did the Franco regime also die then? You don’t have to act interesting: yes, for obvious reasons; We must not be naive: no, because the past never passes: it is a dimension of the present without which the present is mutilated. The best thing you can do with the past, starting with the darkest one, is to try to understand it: it is the only known way to dominate it and prevent it from dominating us, forcing us to repeat the same mistakes over and over again. In other words: it is impossible to do anything useful with the future without always having the past in mind.

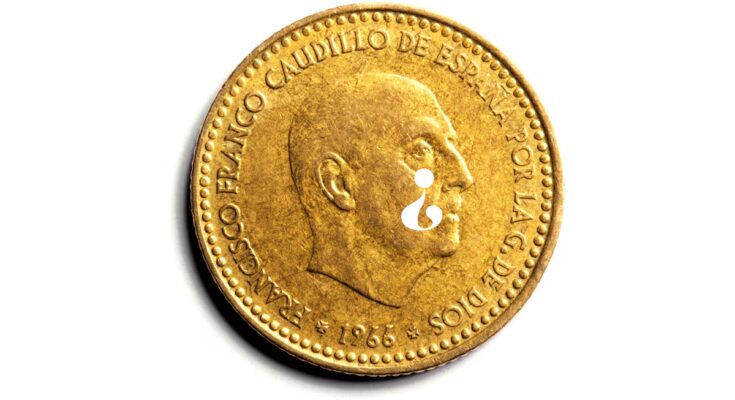

As for me, the insurmountable disgust that death produces in me prevents me from rejoicing even over the death of a sinister and bloodthirsty individual like Francisco Franco.

The truth is: I don’t know what the hell we’re celebrating.