Fairgoers arrived at the gates of the Palacio del Pardo when it became known that the dictator was beginning to disappear. There were those selling churros, cotton candy and sugared almonds. Those that offered religious objects or biographies and postcards of Francisco Franco. The image that Miguel Ángel Aguilar outlines in a very pleasant way There was no custom It is memorable because that custom brilliantly conveys the popular atmosphere of those hours. Madrid seems more authentic here than in the very long lines to greet Franco with genuine emotion at the Palacio de Oriente. Dean Aguilar looked as always and in his memory he now sees the journalists and international correspondents waiting for the news, he contemplates with a mocking smile the fanatics who appeared at the doors of the Palace where the Caudillo issued death sentences to swear eternal loyalty to him and above all he remembers the curious people who wandered around the Pardo “like simple wayfarers”.

They were neither regime elites nor mobilized citizens. These common people, the Francoists, were the backbone on which democratization was activated starting from the government of Adolfo Suárez. The precarious opinion polls of the time, used by Sánchez-Cuenca and Fishman in their excellent and provocative The traces of the Transition, This is what they seem to indicate: “Between a quarter and a third of the population was loyal to the dictatorship, while the vast majority was in favor of democratic changes and reforms or preferred to remain on the sidelines, in a certain apolitism.”

When Franco was already mega-intubated in La Paz and the headlines announced that there was no hope, various information was published about a museum project dedicated to the Caudillo by the Grace of God and his transcendent legacy. We also thought about its location: the Palacio del Pardo. The urgency of opening a new stage, disconnecting from the previous one, caused this ultramontane project to abort while the Valley of the Fallen became the promontory of fear for too many decades. But El Pardo, as a microcosm of the dictator’s dark, authoritarian Spain, had a cultural expression that should be projected as a democratic memory lesson in schools. The masterpiece that is the documentary general report, After a conversation between the trade unionists Marcelino Camacho and Nicolás Redondo, we are shown the main actor walking along the avenues of the Palace, entering it and with him we visit the rooms of that palace of terror while the voice in worn out It explains how the institutionality of the regime was configured and the absolute power exercised by the corrupt Head of State, whose hands trembled but did not hesitate to kill until the penultimate day.

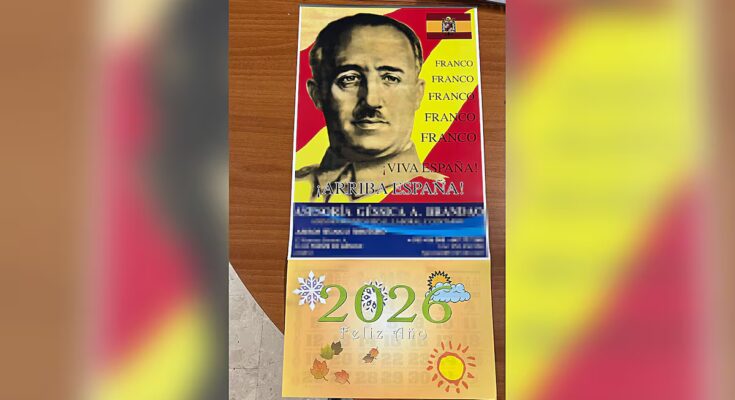

Pere Portabella’s film, conceived from a perspective of rupture, projected a liberalizing fervor that Spanish society, without proclaiming it, had turned the page on. But that page was turned without democracy taking on the mandate to build a common memory of an era that the best historiography has repeatedly described as a black page. And if he took charge of it, he did it late and failed to do it with an inclusive will. For many, for too many, Franco has even returned to being a banal pop icon. The recovery has accentuated during this legislature, as analyzed by the deputy and journalist Francesc-Marc Álvaro in The Franco regime in the times of Trump (will have a Spanish translation), when democratic degradation facilitated the breaking of a taboo: Vox’s praise of Francoism. They are the signs of the times, but it is a mistake to resign ourselves to accepting the return of the mummy as a sign of the times.