Her fighting name was Karla. Singer, prostitute, transgender person. Its setting was the decadent center of Ciudad Juárez, a city in northern Mexico famous for killing its women. Karla was murdered on December 22, 2015, the case was immediately closed and the crime was not solved. For the artist Teresa Margolles it was a brutal and painful blow. She had worked for years with Karla, who opened up to her the world of those trans people who survived with dignity the demolition of the historic center of the city of Chihuahua, the destruction of its cabarets and nightclubs by official morality. People he had photographed in their positions of resistance, so when he heard the news of the murder he collapsed. “They killed her because she was poor, because she was old, because she was a sex worker, because she was trans,” Margolles says.

The artist photographed her friend dressed in white, with crystal heels, her well-combed fringe covering her forehead, behind a mound of earth, witness to the destruction of what was her workplace. The black and white photograph is an artistic project that also includes an audio testimony of the crime, a facsimile of the death certificate and a stone. “She was working and supposedly some guys came to request her services. She trusted her and brought one of them here note down (homosexual) unfortunately that day she was taking drugs with the boy and the boy asked her to turn around, they were walking, he put her against a wall and tortured her, beat her, hit her with stones, destroyed her face. They damaged her very seriously, they massacred her, they tortured her”, says the voice that accompanies the installation. “For us transgender girls it was a surprise. Maybe they did it for fun, we don’t really know what happened”, he adds.

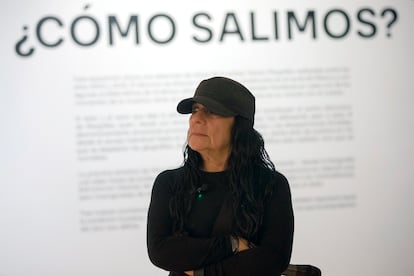

The rawness of the story is a characteristic of the work of Mergolles (Sinaloa, 1963), who confronts people with his art, which delves into the violence and impunity that ravages Mexico. The tribute to her friend occupies one of the rooms of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Monterrey (MARCO), the large art gallery in northern Mexico which, starting this weekend, is organizing the first exhibition in America dedicated to Margolles, one of the greatest exponents of contemporary art.

The exhibition, entitled Teresa Margolles How do we get out? and will be open until March 22, 2026, brings together 23 works from 18 projects created since 2003 and constitutes an example of Margolles’ lacerating testimony of pain. “Karla’s murder went unpunished. The case was closed and the only thing left is my friendship. I said: ‘What can I do for you?’ And the way to do that is to always preserve her memory. Remember that you don’t forget, at least in art. In art we will pay him the best tribute we can have. And mine is that they give him a chance in museums,” says the artist during a visit to the exhibition organized for journalists.

Margolles’ exhibition occupies 1,400 square meters of the museum and brings together pieces that show the commitment of this solitary artist, of few words, serene, tireless. Margolles has documented with his work not only the pain that divides his country, but also the traumas of Latin America, a fertile region of violence, bestiality, impunity, but also a land of resistance. One of the most touching projects of the exhibition is entitled We have a common threadwhich displays a series of embroideries created by women from Nicaragua, Panama, Brazil, Guatemala, Puebla and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The fabrics are soaked in the blood of murdered women, because the artist works with remnants of violence (windshield glass shot during violent events, water with which the authorities cleaned crime scenes, for example), fluids or human footprints, because for her art is a tool to talk about death and pain.

One of the fabrics, When most of us were Sandinistas, It was embroidered by artisans from Masaya, a city in southern Nicaragua that is said to have been a center of resistance during the Somoza dictatorship (1934-1979) and to have resisted the current regime of Daniel Ortega, who bloodily suppressed the protests of his neighbors. The fabric of the exhibition is soaked in the blood of a woman murdered in Managua, the capital of Nicaragua. “When they smelled the fabric, the smell and the blood, the memory came back to them and they said: ‘Look, when we were all Sandinistas’. They made the drawing together, I wanted them to discuss, to talk about when they were Sandinistas,” says Margolles. This installation is accompanied by videos of the weavers, who in the case of the Nicaraguan women show a conversation in which they remember when young people were sent into the jungle to defend the Sandinista revolution due to a US-sponsored war of aggression during Ronald Reagan’s time.

Margolles also explores the drama of migrants. In his project entitled Voyagethe artist brings together photographs of the exodus of Venezuelans through Colombia. Between 2017 and 2019 he spoke to more than one hundred Venezuelan workers who worked on the Simón Bolívar International Bridge, which connects the country to Venezuela. Margolles requested the participants’ T-shirts to create a powerful work with these sweat-retaining pieces: he shows in huge color photographs the male bodies, their torsos, as they take off their T-shirts. Their faces cannot be seen, but the humility of their clothes is a true statement, because they testify to the effort at work, the desire for a better life, the harshness of the exodus. The installation is accompanied by concrete cubes, within which Margolles kept each of the shirts and marked them with each migrant’s initials. Buckets containing the dramatic sweat of migration.

However, the pain of violence in Mexico is the most important theme of the colossal exhibition set up by MARCO. Visitors can listen to the chilling sounds of the morgue, through headphones that reproduce the sound of knives being sharpened or that of saws in what appears to be the horrific cutting of human bones, because Margolles studied forensic medicine and learned from the morgue that corpses talk. At the end of the nineties he joined the SEMEFO (Forensic Medical Service) collective, which combines performance, installation and sound to question the limits between life and death. Another piece is titled Approaching the accident site, commissioned for this exhibition, which consists of marking with water the places where the murders occurred in Monterrey between January and October this year. The installation includes 30 red-hot iron plates on which droplets of water absorbed at crime scenes fall.

“It is a sound sculpture”, explains the artist, “because each drop that falls has a different rhythm, a different emotion. The water that falls is that which marked the place where the body of a violent man fell. With a sponge you get the water. The drop that falls on the hot iron reflects when they tell you: ‘Your son is dead’. You feel the blow, but always, even if it evaporates, the trace will be there, because a murder destroys a family. That constant trace destroys a neighbourhood, a city, a country evaporate, yes, but what happened will always remain marked, it will never be erased”, says the artist about his sound work, a sculpture that evokes the victims of violence and whose title derives from forensic terminology.

His interest in avoiding oblivion is also shown in works such as Bankingcreated in 2002 in Puebla, a bench that could be found in any park, but which was made with cement mixed with the water used to wash corpses after autopsies. OR The witnessfrom 2013, a series of photographs in which trees, penetrated by stray bullets, remain wounded, but alive. OR Backlash / The power2022, a dress made with fragments of glass from the windshield shot during the events that occurred in Culiacán during the so-called “Black Thursday”, on October 19, 2019, during the rescue of Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s son, when shootings in different parts of the city left thousands of citizens defenseless, dozens of detained soldiers and criminals who escaped from prison.

The exhibition is set up with great care and created to challenge the visitor, because it is difficult to remain indifferent to the facts denounced by Margolles. “It collects the testimony of the pain of what we call contemporary life,” explains Taiyana Pimentel, director of MARCO, curator of the exhibition and who has collaborated with the artist for several decades. “The pain and void left by human loss in society is the discursive center of Margolles, who from his first forensic moments outlines, step by step, the emotional collapse caused by violent deaths and forced disappearances, from the individual to the collective field,” he adds.

This exhibition includes three commissions by Margolles for MARCO, one of which is an untitled sound installation (although the museum explains that the artist considered calling it Elegy to the homeland), which features 32 windows dismantled from commercial premises located in urban areas affected by abandonment due to violence. Coming from cities such as Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, Culiacán and Monterrey, each glass vibrates to a different rhythm, emulating the particular sound of the train crossing the country north and crossing the border.

“She is an unresponsive creator boom“, explains Pimentel, “which has a work process that has lasted for many years, but has a very peculiar element: perseverance in the discourse. The place that Teresa occupies in the history of contemporary art is related to migrations, borders, violence, related to the pain she has collected, because a very moving part of her work is giving visibility, a face, to the victims, but not for free, but through a fragment, a material, a ceramic, a boot. She is an artist who works from art to recover memory,” says the curator.