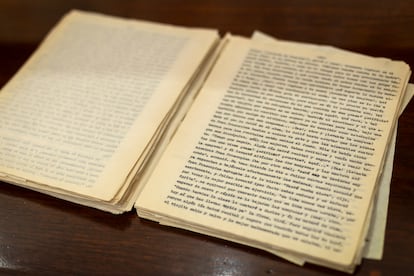

Five hundred sheets have just been deposited in a red velvet box. Aged leaves, yellowish tones, with changes and stored odor. Leaves from a time when writing was done with the hammer and ideas still stained the fingertips. Typewritten sheets at the end of the 70s, which shocked the universe of letters and which still have something to say today.

The manuscript of A world for Giuliothe novel in which Alfredo Bryce Echenique portrays the features of the Limegna upper class from the point of view of an orphan child who lived in a palace, has just been officially donated to the library heritage of the Cervantes Institute, as part of a conference in honor of the writer.

Last Thursday afternoon it falls in one of the classrooms of the Faculty of Letters of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, in Lima. From a small table, Luis García Montero, director of the Cervantes Institute, and Ángel Esteban, professor of the University of Granada, solemnly explain the value of the event. «The best way to commit to the future is to know how to receive the best legacies from the past», says the first. “It will enrich the historical heritage of the language,” adds the second.

Flanked by both, from the wheelchair, Bryce Echenique – stripes to the side, draws color camel and without the mustache that one day he began to shave, he remains undaunted. His face shows no sign of emotion. He seems absorbed in some distant place. Not the slightest smile appears when his interlocutors review the praise his most acclaimed novel has received. What Pablo Neruda defined as the “splendid suit of lights with which he threw himself into the ring” of literature. You’ve probably heard praise many times over the last 55 years.

The truth is that the importance of the event lies above all in the fact that it involves the discovery of a treasure. Some time ago, during a conference in Madrid, the son of Julio Ramón Ribeyro – the famous writer of the unfortunate who welcomed twenty-year-old Bryce Echenique to France – told Ángel Esteban that he had found some unpublished stories by his father in the wardrobes of his house, in the residential neighborhood of Parc Monceau, in Paris. Esteban, who suspected that the furniture housed other jewels, asked her to please allow him to examine those documents. Julito, as the sole heir of the author of The temptation of failurehe accepted.

In April the academician traveled from Granada to Paris. And for a day he rummaged through some built-in wardrobes in the hallway of the apartment on Van Dyck Street. Two hours later he found a voluminous folder with manuscripts by other writers. The largest file caught his attention. When he read the cover he froze: A world for Giulio. Alfredo Bryce Echenique. The questions followed one another: how many years had it remained there, collecting dust? Why did Ribeyro have it? Was it a gift to boost his career or an unrepaid loan?

Esteban immediately reported the discovery to Germán Coronado, director of the publishing house that owns the rights to his work. It was Coronado who proposed the idea of donating the manuscript to the Caja de las Letras of the Cervantes Institute, at its main headquarters in Madrid, where the work of great creators in all disciplines of art resides. Julito Ribeyro Cordero gave his approval on the condition that Esteban represent his family. And indeed, that was the case. The manuscript traveled from Paris to Lima and then moved to Madrid, its final destination.

The story expands. Ribeyro’s son tells EL PAÍS by telephone that, in reality, the first version of A world for Giulio It had already been discovered a year and a half ago. It appeared in the library of his apartment at Villa Violet, also in Paris. It is not explained how the pages got there. “I don’t know how the hell it happened. Sometimes I brought my father’s material to my house. I must have taken it by mistake. In any case, I think it’s a nice gesture that Ángel (Esteban) made all the effort to crown this event in San Marcos. Alfredo (Bryce Echenique) was like an uncle to me. In the relationship he had with my father there was never any envy, which is not so common in such talented writers,” he explained. he says.

Almost sixty years after its publication, A world for Giulio It was many things. The first time that a wealthy man rebelled, ironically, against his social class; the literary initiation of several generations in secondary school; the book they gave to the ambassadors before starting their diplomatic mission in Peru; the novel finalist for the Short Library Award, abandoned in 1970 due to Carlos Barral’s breakup with Seix Barral; the first book in the Barral Editores catalogue; the project where Bryce Echenique’s first wife warned him they would separate if he didn’t complete it; “goodbye” to his country, the one he left on a boat in 1964; the work that inspired a film in 2021, but above all the splendor of a writer who at thirty years old found the echo of his voice and sowed the seed of his literature.

Returning to the San Marcos University, a tribute organized by professors Agustín Prado and Carlos Arámbulo, Bryce Echenique takes the floor. The audience remains silent. The wait for what he has to say is cooking. At 86 he confesses that he doesn’t remember why he gave his manuscript to Ribeyro, the friend ten years older than him who invented the title of his first book of short stories (Closed orchard). He is not afraid to spoil the version that has spread in the media: that he gave it to him in gratitude for being his literary mentor. And then the laughter. “Julio Ramón gave me his things to read and so did I. I gave them back to him honestly and he dishonestly threw my manuscript away,” she says.

Goodbye to protocols. People celebrate the frankness of those who have not always been frank. More than 15 years ago, Bryce Echenique’s reputation was tarnished by a series of plagiarisms. Those who created the series of lectures assure that this does not harm his narrative work and that the time had come for him to reunite with his alma mater. The ball is not stained, Maradona would say.

Be that as it may, Luis García Montero concludes with a tasty anecdote. In 2019, the writer went to Madrid to donate his books to the Caja de las Letras, but forgot the entire arsenal in Lima. Both managed to evoke personalities and form a collection of their first editions. “He can lose whatever he wants and his friends, as good readers, will take care of keeping everything,” he points out, looking at the velvet box. Five hundred pages of a book that has aged well.