Qwhen God brought a Colt and a miracle smelling of gunpowder, he gave: Battle of San Sebastianwas released in the United States in 1968. One of those slightly crazy films that hits you like wafers on a bar. Because that’s exactly what happened: a frontal clash between holy water and tequila, between rosaries and kegs, between the faith of a simple man and the face of Anthony Quinn – a pile of flesh and charisma that could make someone believe in the resurrection just by raising an eyebrow.

Henri Verneuil, adopted son of the Marseillais who survived the Armenian genocide, master of French thrillers, director who knew how to make Gabin sweat and Belmondo dance, one day had a crazy idea: what if we made… a religious western? Not a westerner with a priestly background, no. A western story of faith, deception, miracles and redemption. With the Yaqui Indians, who terrorize Mexican farmers, a fake priest who doesn’t believe in anything, and Ennio Morricone as director for an enveloping spaghetti-guacamole western soundtrack. Suffice it to say: crazy bet. A strange, colorful, multi-genre film.

Holy fraud

In 1968-1969, we were in the midst of a wave of westerns, from Italian B series to Hollywood locomotives: Clint Eastwood triumphed with Hang high and shortand Sergio Leone destroys everything with his legend Once upon a time in the West. In this concert of “pure” genres – codes, duels, saloons and dust founded in orthodoxy – the mystical and Mexican Verneuil appears as a heretic. Retrospective irony: what seemed like a violation of the rules has now become the most valuable singularity.

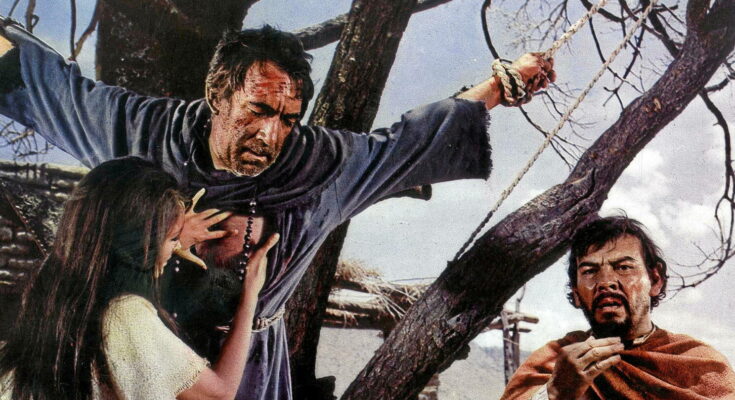

The context chosen to set the story actually takes us away from John Wayne’s sandbox. Henri Verneuil sets his camera in Mexico, in 1743. Leon Alastray (Anthony Quinn, in all his magnetic glory) is an outlaw pursued by Spanish royal troops (Mexico has yet to gain its independence). He takes refuge in a Franciscan church run by the good Father Joseph (Sam Jaffe, the gaunt face of a saint). The latter refused to give it up – faithful to the spirit of the Gospel and not to its hierarchical order. Immediate sanctions: Father Joseph is exiled to San Sebastian, a village lost in enemy territory, ravaged by raids by Yaquis Indians. In other words, we send it to the slaughterhouse.

Breakthrough miracle

The old monk dragged the rebel Alastray there. Having just arrived, the priest received a bullet that sent him ad patres. A little tip from this scenario: to protect himself from the sun, Anthony Quinn wore the late bishop’s hood. And there is something strange: the villagers, hiding in the mountains, believe that Leon Alastray is the new priest. Although Alastray denies it, repeating that he is not the servant of the Church that the villagers expect, no one listens to him. They were so desperate that, for them, the robes became monks. Resigned, misunderstood, the bandit Alastray works, with the means at hand, to assume the role everyone wants to see him play… And then begins one of the most beautiful sleights of hand in popular cinema: an atheist who performs miracles in spite of himself.

Because Henri Verneuil does not give us an edifying parable about rose water. He shows us a con artist who, out of pragmatism, out of pride, out of desire (the beautiful Kinita, played by Anjanette Comer, has nothing to do with it), and maybe – just maybe – through a bit of rediscovered humanity, will achieve what no one expected: giving hope to a broken people.

The miracle is not divine but human

Alastray doesn’t preach. He acted. He fortified villages, acquired weapons, organized defenses, turned frightened peasants into warriors. He wasn’t talking about God: he embodied what people would expect from someone sent from Heaven. A protector. A savior. A leader who neither abandons them nor bails them out.

And this is where this film becomes very interesting: the miracle is not a divine miracle, but a human one. Henri Verneuil, with his watchmaker’s precision and suspenseful storytelling, shows us that the villagers’ faith creates miracles. Their belief in this false priest forces him to be better than he is. Falsehood becomes truth through the grace of collective hope.

We think God’s Left Hand (1955) with Humphrey Bogart, but Henri Verneuil goes further: his hero does not seek redemption, it falls on him like a curse. Or as a gift – who knows. He acts as an unconscious prophet. Henri Verneuil was also pleased to give him a young woman who was ready to give herself. The bandit rushed to devour him but, at the last moment, something held him back… It was as if the ecclesiastical character he had played to deceive began to devour him from the inside.

Ennio Morricone is in fine form

Opposite Anthony Quinn, Charles Bronson plays Teclo, the right-hand man of the Yaqui chief “Golden Lance.” Bronson, granite face, wolf eyes, represents a “bad guy” who is not just evil. He has his reasons, his past, his logic. Here again, Henri Verneuil, true to his taste for relief characters, rejects easy Manichaeism. The Yaqui tribe rejected evangelization because of loyalty to their traditions, to their ancestors, to their territory which was little by little encroached on by Spanish colonialists.

Then there’s the music. Ennio Morricone, not yet a global legend, imposes, in some accounts, the tension that precedes the action and cavalcade. Beautiful, effective, that’s Morricone. Add to that Armand Thirard’s photography (Cinémascope, opulent Mexican settings, end-of-the-world lights), and you have a film that exudes grand spectacle, yet retains soul.

Critical failure, forgotten treasure

When it was released in France in March 1969 (the events of May 68 delayed it), Battle of San Sebastian wasted. Too slow, too religious, too unorthodox. French critics, then in the midst of the New Wave, did not understand this extraordinary western, set in the 18th centurye Century, helmed by a French filmmaker, is made in English, with Hollywood stars and an Italian-Mexican team. Too much of everything, not enough of nothing. Commercial success is not there.

However, when you think about it, the film shines with an extraordinary light. This is a metaphysical western, a film about the power of belief, about deception becoming truth, about a community rebuilt through faith – even if this belief is based on misunderstanding.

A film that believes in something

Henri Verneuil, who survived exile, knew what “rebuilding” meant. Without being completely his own, this story carries some of his history. Filmmaker Mayrig knows what it means to wear a mask to survive, he’d rather change his name (he was born Achod Malakian). And he puts it all into this film: his rigor, his sense of spectacle, his thoughtful humanism, his taste for expansive stories and complex characters.

Battle of San Sebastianit’s a film that shouldn’t exist. French western religious film filmed in Mexico with American and Italian music. A film about a fake priest who saves true believers. A film where the magic is human – not God. Anthony Quinn is fantastic, inspiring Morricone. And Verneuil, this great popular film artist, signed one of his most personal, riskiest, and most unfairly forgotten works.

To find

Kangaroo today

Answer

So yes, this film has its own running time. Yes, sometimes it’s stiff. But it has a uniqueness that makes it valuable. This is a film that believes in something and doesn’t settle for the antics, action, and gunplay of big cinema fights. This needs to be reviewed again Battle of San Sebastian not as a clichéd fight between Mexicans and Yaquis, but as a fight between faith and doubt. And that is already a small miracle. Thank you Achod Malakian!

Battle of San Sebastian by Henri Verneuil, 1968, 1 hour 56. French-Italian-Mexican co-production, with Anthony Quinn, Charles Bronson, Anjanette Comer, Sam Jaffe, Jaime Fernandez. Music: Ennio Morricone. Watch on Arte, Monday 17 November, 20:55.