While I was in Trento for work a few days ago, walking in the historic center, I came across a pro-Palestinian demonstration that attracted the attention of citizens and onlookers. This event took place under the supervision of the Police, an important garrison of our Republic. The main streets, usually busy with tourists and families, were lined with flags and banners and accompanied by singing.

However, apart from the excitement of the square, there was another feeling that was also felt: the concern of the traders.

When talking to some of the center’s operators, dissatisfaction was clear. “The place, which is usually full every night, is empty today,” said a waiter from a restaurant in the central area. “Today you can never find a free table. But today, we are losing a lot of revenue,” he continued.

This does not appear to be an isolated case: according to some shop owners, demonstrations, especially if not properly permitted, will result in slowdowns, temporary closures and a significant reduction in tourist and local flows. “We don’t know whether they have permission or not, but actually we are the ones who bear the consequences, and the city’s economy goes with us,” growled another trader.

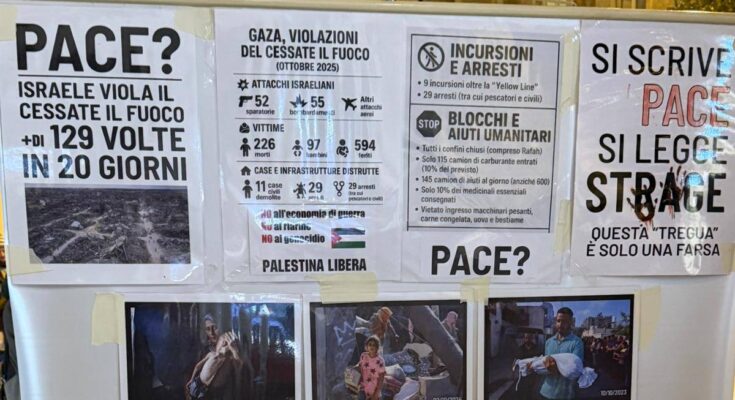

A sign with allegedly anti-Semitic content also appeared among the attendees, causing anger and concern among those present. The message expressed clear hostility towards the Israeli people, more than just political criticism. A serious episode that cannot be minimized and has reignited the debate regarding the boundaries between freedom of expression and incitement to hatred.

Protest is a fundamental right. However, when the square becomes a means of ethnic or religious hostility, this right is violated. This is not just a matter of public order: it is a shared responsibility. A protest is truly democratic only if it is based on mutual respect, not on words or actions that incite division.

During his speech, one of the speakers several times used the concept of “resistance”, recalled the “No King” demonstrations in America and spoke about the growing discontent in the United States. According to the speaker, the slogan would express rejection of any authority deemed to be imposed. However, it remains unclear who or what this “resistance” is aimed at: specific governments? global economic system? or, in a more radical sense, the institutions themselves?

In Italy, the term “resistance” is associated with the struggle for freedom and democracy. Hearing it today interpreted in an antagonistic or anti-institutional way raises reasonable questions. Where do the protests end and where do challenges to legality begin?

The “No King” movement, which was born in the United States as a critique of the centralization of political and economic power, has in recent months been adopted by very different groups: some have social goals, others have a more extreme accent. If this message is truly destined to expand, it is important to understand in what form: as a demand for greater justice or as a rejection of democratic rule?

The real point is how to reconcile the right to protest with respect for the rules and life of the city. The square is the garrison of democracy, but the shops and restaurants also represent an important part of the community and its economy.

The real challenge is finding a balance: ensuring that differences of opinion do not become an excuse for hatred or violence, but become an opportunity for civil confrontation. In democracies, resistance is never against the state: resistance is a drive to make the state more just and humane.

One thing must be clear: protesting is a sacred right, but it must be done legally, with respect for those working and without causing damage to the city. This was not the case with the demonstrations in Trento, but similar incidents in the past (which turned into clashes, destruction and damage to shops) show how short measures are taken.

When a protest turns violent, it is no longer a protest. And showing offensive or discriminatory signs is also violence. Any form of rebellion against democratic institutions must be opposed firmly and in full accordance with the law, without any hesitation or doubt.