Adapt to cold climatesSuddenly there are mosquitoes even in Iceland

Iceland was previously one of only two mosquito-free places in the world. Now that has changed: tiny insects have been discovered there for the first time. Is climate change the cause of its spread?

Iceland has been largely safe from mosquitoes so far. This island of glaciers and volcanoes was previously the only mosquito-free place in the world, apart from Antarctica. The cold climate contributes to this.

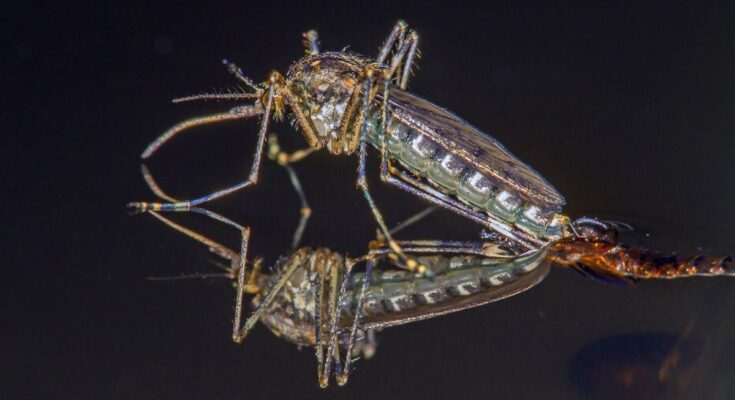

That’s over now. Mosquitoes of the species Culiseta annulata – the ring fly or big house mosquito – have been discovered in a natural environment for the first time in Iceland. Three specimens were discovered in mid-October in Kjós, 30 kilometers north of the capital Reykjavik.

Björn Hjaltason discovered it. He hangs bait on his farm – actually to attract moths. “I immediately realized that I had never seen anything like this before,” he wrote on Facebook after his discovery.

Ringworm doesn’t seem to mind the cold of Iceland

The Icelandic Institute of Natural History then examined the mosquito. There are two girls and one boy.

Because their ring-shaped legs are white, ring gnats are often confused with the Asian tiger mosquito. This species is widespread throughout Europe. It has adapted to a rather cold climate. It survives the winter as an adult in a sheltered place – for example in a basement or barn. Everything suggests that this species of mosquito is cold hardy and can survive Iceland’s harsh conditions, says the Natural History Institute.

In early November, more mosquitoes appeared in Iceland: They were detected in a cage on a farm in Ölfus, located south of Reykjavik. This time it is a specimen from the genus Culex. More specimens were found than in October.

Mosquitoes have long been native to Iceland and its equally cold neighboring countries: There are two species of mosquito in Greenland and 28 in Norway. Pupae hibernate under the ice and emerge in spring as soon as the ice melts.

Chironomids, black flies, and biting midges are common

However, Iceland hasn’t been completely mosquito-free for long. There aren’t any mosquitoes here yet – but there are. Lake Mývatn – Mosquito Lake – in the north of the island is famous for this. In summer, flocks of mosquitoes hover in huge clouds over the water. Because it looks like a cloud of smoke, the fire department is often called there, a travel service provider reported. These are the Chironomidae – chironomids – which, unlike ring flies, do not bite.

Black flies also live on the island – Simuliidae, Icelandic Bitmý. In this small species, the female stings. And Lúsmý has been spreading throughout Iceland for ten years. This is the Icelandic name for the biting midge – or Culicoides reconditus. They annoy humans with painful bites. A warmer climate has resulted in a variety of new species settling in Iceland in recent years, according to the Icelandic Institute of Natural History.

Iceland has a number of potential breeding sites for mosquitoes, such as swamps and ponds – perfect habitats as they like damp places. But unpredictable winters make it difficult for mosquitoes to breed: temperatures can suddenly rise and thaw, then get cold again. This stops their life cycle.

Record heat in May

However, temperatures on the island are getting hotter: they are rising four times faster than the rest of the northern hemisphere. This was clearly visible in May. At Iceland’s Egilsstadir Airport, 26.6 degrees Celsius was measured on May 15, the highest temperature in May since records began, scientific association World Weather Attribution said. The temperature was more than ten degrees above average. Globally, May was the second hottest month since weather records began.

May is not usually a warm month in Iceland, said meteorologist Halldór Björnsson of the State Weather Service in Deutschlandfunk. “It is very rare for the thermometer to rise above 20 degrees Celsius. This time we had ten consecutive days with such high temperatures. 94 percent of our measuring stations set a new heat record for May and the record for the whole of Iceland was broken three times.”

With climate change, mosquitoes are increasingly spreading throughout the world. The weather is getting warmer, summers are longer, and winters are milder. Increasing temperatures make them grow faster and live longer. But experts warn against linking the discovery of mosquitoes in Iceland to global warming. Climate change alone cannot explain this phenomenon.

Mosquitoes transmit deadly diseases

Disease-carrying mosquitoes are on the rise worldwide. A recent study shows that the risk of infection increases as the virus spreads to new areas. Based on this, 45 species were introduced into areas where they did not actually live. Of these, 28 species have successfully reproduced. They travel as stowaways, for example as larvae in aquatic plants.

“Mosquitoes are one of the most important disease-transmitting animal species in the world,” explains co-author Franz Essl, a biodiversity researcher from the University of Vienna, at ORF. They can transmit serious and even fatal diseases through their bites. As a result, more than one million people die worldwide every year. Introduced species such as tiger mosquitoes transmit malaria, Zika, chikungunya, and dengue fever.

Icelandic ring flies also bite, but according to the Natural History Institute there they are not dangerous to humans. This type of mosquito does not transmit any known infections.

Mosquitoes come to Iceland by sea

It is not yet clear how this newly emerged mosquito species got to Iceland. Ring flies can be carried by ship, aquatic ecologist Gísli Már Gíslason of the University of Iceland told France 24. The insects are often carried by planes and ships. This may just be a coincidence, “but it could also be because the weather is getting warmer. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why the number of insects is increasing much faster than before.”

Several years ago, a mosquito was found on a plane at Keflavik airport; it belongs to the arctic species Aedes nigripes. But it hasn’t settled in Iceland.

It is not yet clear whether the two mosquito species have settled permanently in Iceland. First, they have to survive the Icelandic winter. Researchers want to check it out in the spring.