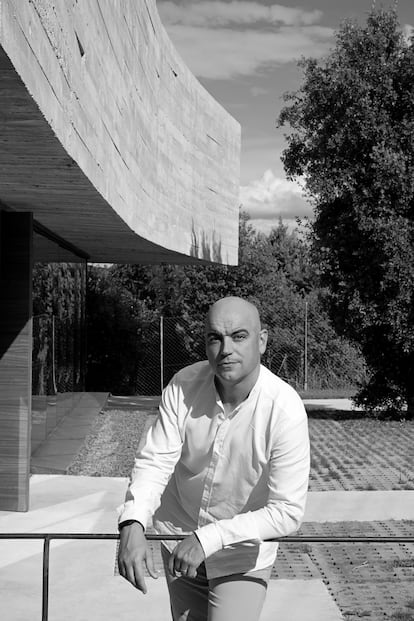

Before, when this was just a field, there were two oak trees here. Also an extraordinary view, looking north, over the Guadarrama mountain range and its Pedrezuela reservoir; To the south, a series of houses that look like second homes along a street called Roble. But above all there were two oak trees. When you begin to visualize a construction in a specific place, when the time comes to decide what and how to relate to the environment, you start with these things. Moisés Royo (Barcelona, 44 years old) noticed them when he started imagining this project, number 472, by Muka Arquitectura, the studio he founded 18 years ago. He decided to leave them where they were and to conceive the work around them: what followed is perhaps his most famous work today, the Oak House, just nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Prize, a concrete house on three floors of ascending intimacy, in which the limit between inside and outside is blurred, a triumph of the use of strong materials and ideas subjected to delicate concessions; an example of how architecture can be, in short, in itself what decorates a landscape.

Royo started with oak trees. “The simplest thing would have been to cut them down and plant others: it’s fashionable to put as many trees as there were before. But preserving them helped us generate the position, shape and relationship of the house with the environment”, he explains today. “Architecture has this double reading; it is an imposition because we continue to plant a construction in a place where there was nothing; but it is also something that must bend to that landscape. The trees need an aura around them and the house, next door, so compact and compressed, reflected that tension between architecture and nature. So it has many straight lines, the hand of man, but there are also very subtle curved lines that remind us of that subordination to the landscape.”

Then came the concrete. “As a consequence, not as an imposition,” warns the architect. “I wanted this house, because the place was so steeped in landscape, to be understood as a cave, a space to escape into. Hence the stone character. This is how it should relate to these views and these trees.” Once the core material was sorted out, some of the shapes started to make sense. “The elements support that heavy covering, but at the same time have a floating condition. The concrete would give us that play of being a heavy element but at the same time weightless.”

The rest of the house, its spaces and the structures they would have, came later. This time the guide was not the vegetation but the sun. “The natural light, the southern one, is on the access road, in the position where the view is worst and where the house must be closed for privacy reasons,” complains Royo. “And the views are oriented to the north, where I wanted to open a large window. Before placing the openings, when it was just the concrete floor, I knew that I wanted to orient all the spaces towards the landscape. All the spaces had to communicate: they had to be connected by that landscape. When you look at the section of the house, the light from the south enters through the upper level, but manages to penetrate and reach the lower level facing north. Natural light floods the space. The sun’s rays also hit the floor, the walls. The passage of the day is captured, filmed, by the sun streaming inside the house.”

That verb, filmed, is not arbitrary. Speaking from the living room of Casa Roble, immersed in the white light that enters from the enormous window, Royo reveals himself to be a metaphor-generating machine to explain his work. The most recurrent is the one that compares architecture with another of his great passions, cinema. “The architect develops events like the director. We have the enormous ability to influence people’s perception. In cinema, with image and sound; we with science, mathematics, engineering and even art. The user is spectator and protagonist: time is marked with more light, less light, more or less rough surfaces. I like to understand it from this partial analogy.”

It is less difficult to look for Royo’s imprint in ideals as well as in concrete details. “It’s difficult to find a common thread in the final result: my materials are not the same, nor are the shapes. Zaha Hadid has easily recognizable geometries, but I don’t,” he specifies. “I see my work as I see life: as an accumulation of scars. The remains that remain after an experience. When I do architecture, I don’t have in mind Alvar Aalto, Reima Pietilä or Kazuyo Sejima. Nor the church of a town that I went to visit as a child and where I found the detail of an anonymous architect. But all this is in my retina. It’s like when you are a child. First you look at your parents to learn how to walk, how to use cutlery. Then there comes a moment when, building on that learning, you now fly on your own.”

Royo grew up appreciating the work of the architect who does not pretend to be an author but rather puts himself at the service of every context. “I grew up in Ciudad Real, which has a generally anonymous architecture, where working with materials is very powerful. Stone, tiles, bricks: everything is designed to last.” Another influence: «My father was originally from Portland, he worked in Portland cement: in the summer I visited the construction sites with him and saw many cities with that type of architecture». Upon entering university, where she studied with José Manuel López Peláez and Javier Frechilla, she asked to do her Erasmus in Finland to get to know her first love, the Finnish Alvar Aalto.

And this brings us back to Casa Roble and its interior, organized around an invisible spiral. “At the bottom the more social uses begin to occur; as you go up, the level of privacy also increases,” explains Royo. The entire spiral orbits around an element that is not exactly in the center. “The fireplace,” Royo smiles. “It is slightly inclined, it is the point of greatest tension in the house. Above it there is a structural element that supports the large ramps of the roof. So the heat from the fireplace rises up to the shower. For me the bathroom is a thermal spring, a sauna.”

—Like Finnish saunas for example?

“The place that purifies your body and spirit,” he completes. There is that concrete cylinder, how a concrete influence can be brought to the abstract. “You probably aren’t able to consciously perceive that union, but it’s there. Like that father who is always there, even if he’s not physically there.” Here were two oak trees. Now there are two oak trees and everything a man has learned in a lifetime.