Over the next 15 years, Spain will have to meet greenhouse gas reduction commitments within the EU, which should completely change its energy system and introduce important innovations for citizens. Although today the winds are not very favorable to the fight for the climate, the country must reduce the emissions that cause global warming by 32% in 2030, compared to 1990. And the Twenty-Seven brought to the Belém climate summit the commitment to cut between 66.25% and 72.5% by 2035, and approved the transformation into law of a joint reduction of 90% by 2040. We must we still have to wait to see how this last percentage is distributed among the countries, a common objective reconfirmed – with strong concessions – by the majority of European political forces, with the exception of the far right and the Spanish PP. However, this level of cut is already very close to the grand final goal of climate neutrality or net zero emissions (which means reducing them to a minimum level that can be offset by forests and other sinks) set for the 2050 horizon.

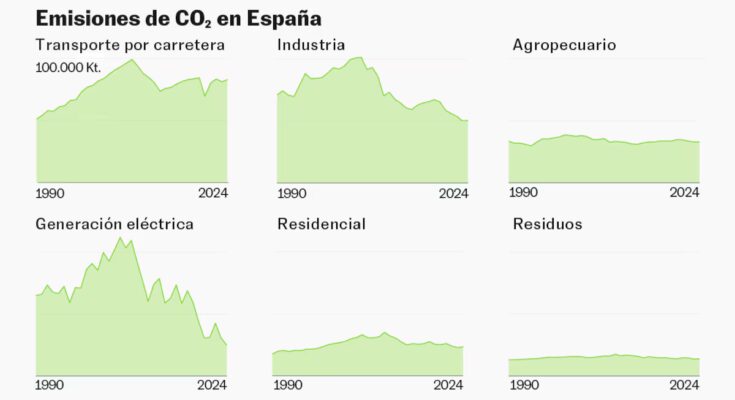

That’s not a long time, given the enormity of the challenge and the growing forces working in the opposite direction around the world. A preview of the official emissions inventory shows that in 2024 Spain generated 268 million tons of CO₂, which represents only a 6.3% decrease compared to 1990. However, decarbonization is already underway and begins to leave other more positive data. As Luis Rey, researcher at the Basque Center for Climate Change (BC3) participating in the Observatory on Energy Transition and Climate Action (OTEA), explains, although there has been practically no progress in key sectors such as transport or residential construction, significant progress has been achieved in the electricity sector, thanks to the great expansion of clean technologies such as photovoltaics and wind energy, and the closure of coal-fired power plants. According to Red Eléctrica de España (REE), in 2024 Spain managed to generate 56.8% of its annual electricity with renewable energy and in 2025 it will reach 56%. The goal set by the Government for 2030 is to reach 81% and, despite all the noise against these technologies after the historic blackout last April, progress seems unstoppable.

“The electricity sector will undoubtedly reach 81% in 2030”, is confident Ismael Morales, head of climate policies at the Renewable Foundation, which concerns the almost 13 gigawatts – a power equivalent to a dozen nuclear power plants – which exist with permits to connect to the electricity grid only to install storage batteries, and in technologies such as grid formation which will be activated with new regulations so that unmanageable clean energies contribute to giving more security to the electricity system, like traditional ones. In fact, at the end of October, REE began the qualification tests for the first renewables that require contributing to the dynamic control of the voltage. “With the blackout, everything was blamed on renewables, but there hasn’t been a single piece of evidence that they had anything to do with it,” says Morales, who believes that these improvements for clean energy to become active stabilizers of the system and the possibility that it can be stored on a large scale for when there is no sun or wind will remove any limitations for these technologies to reach, if desired, even 100%.

With renewables, the biggest challenge in Spain is not so much how to keep adding megawatts, but rather preventing their production from being wasted at certain times due to lack of demand. As Morales points out, in theory more generation would be needed due to the shift from gasoline to electric cars, however, this is not happening at the expected pace, at least until now. “The risk is that to achieve the renewables objective, priority will be given to other high-consumption uses, such as data centers, instead of serving the electrification of the economy,” he underlines.

According to the latest data from the 2024 inventory, transport is currently the sector that contributes most to climate change in Spain, with 33.3% of the country’s emissions (30.9% from vehicles circulating on the roads), followed by industry with 18.8%, agriculture and livestock with 12.3%, electricity with 9.3% and residential with 8.7%. As Rey points out, “it is surprising that greenhouse gases are reducing in the industrial and electricity sectors, which are those that are part of the emissions rights market (ETS), while this is not happening in transport or construction”. Precisely one of the big changes expected in the EU consists in the upcoming creation of a new ETS2 market which will also put a price on the ton of CO₂ emitted in these other areas and which companies that sell fossil fuels will have to pay to move vehicles or to heat homes. This new mechanism was supposed to come into force in 2027, but the Twenty-Seven simply postponed it to 2028.

In this regard, a few days ago 26 civil society entities (including CC OO, UGT, Greenpeace, Oxfam-Intermón or the ONCE Social Group) recalled that to mitigate the foreseeable increase in the price of fuel due to ETS2 (estimated at around 12-14 cents per litre), the establishment of a Social Climate Fund is also envisaged to finance measures in favor of the most vulnerable population and micro-enterprises. As they underlined, this fund provides 9,000 million euros for Spain in the period 2026-2032, which they consider essential to anticipate future social problems and avoid cases like that of the yellow vests. However, the Spanish government is currently experiencing a significant delay in its implementation.

Pending the arrival of a price for CO₂ for road transport and the residential sector, and a foreseeable increase in difficulties in driving polluting vehicles in urban areas, the truth is that 2025 leaves better numbers for the electric car. According to the latest industry data, sales of electrified cars (pure electric or plug-in hybrids) already represent 19% of the market this year and are increasing by eight percentage points. However, the vast majority of vehicles circulating in the country continue to burn petrol or diesel. Likewise, there are other sectors where decarbonization is even more difficult.

How far can we go in reducing emissions? As Pedro Linares, energy transition expert and professor at the Comillas Pontifical University, points out, “achieving climate neutrality is technically feasible, it all depends on the deadlines and additional costs that we are willing to assume”. «Let’s say it has a cost, but it is not a utopia», he underlines. By 2050, it is considered feasible to have fully decarbonized electricity, transport and homes, making it more difficult to end emissions from some industrial processes, waste or agriculture. However, by then it is hoped to have CO₂ capture and storage systems, which do not exist today. “What we see in our scenarios is that the technology exists, if you can also change people’s behaviour, so much the better, because it will cost less,” he comments.

Apart from capture systems, it is yet to be established how much carbon dioxide can be offset by forests, which appears more risky after what happened this summer, since what is absorbed by trees can vanish suddenly with forest fires. Furthermore, the Twenty-Seven’s latest agreement includes significant concessions, such as the expansion to 5% of international credits that can be used to cover emissions reduction deficits and the possibility of adding another 5% in the future.

Pedro Zorrilla, responsible for climate change at Greenpeace, believes that the important thing is that the 90% objective for 2040 has been maintained and underlines the great advantages of emission reduction policies: “If cities are created 15 minutes away, with good public transport, the quality of the air and our quality of life will improve”, defends the environmentalist, who underlines other positive effects in the improvement of the insulation of houses, the increase in renewable energy, the reduction of pollution or the change in diet.

Although Linares highlights the additional costs of decarbonization, he at the same time points out that “it is also more expensive to have insurance for your home and you pay for it to reduce possible risks.” Here, if the countries that emit the most do not decarbonize, it will not do much for Spain to achieve net zero emissions to reduce the dangers of climate change. However, this brings other advantages for the country: “For me, the big advantage of the change is not only to be able to have access to local energy, but also to free ourselves from the volatility of fossil fuels,” says Linares.