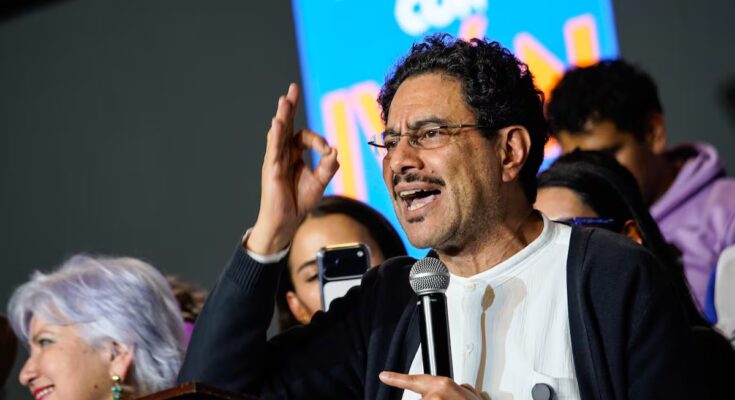

Ivan Cepeda Castro, the left-wing candidate for the 2026 elections, made his first public statement on the streets of Bogota last Friday. Little has been said about the progressive star senator since he won the presidential elections at the end of October, with 1,520,287 votes, so his followers are anxiously awaiting the direction he will propose to win over both dubious progressive voters and those of the centre. This Tuesday he appears leading an electoral poll by the National Consulting Center with 20% voting intentions, and shortly after received the support of a progressive sector of liberalism. Cepeda has a great temporal advantage over the right, which lives struggling to choose a candidate. But with a significant disadvantage, since he is the candidate of the ruling party when the government’s popularity has not exceeded 50% for some time. This last part, however, doesn’t seem to bother him.

“I send a hug of solidarity, brotherly, of total support to President Gustavo Petro for the personal attacks received from the United States government. We take to the streets to demand that the president, the Historical Pact and our political rights are respected,” he said on Friday at the corner of Carrera 7 and Calle 19. He made it clear, in this and other speeches, that his intention is not at all to distance himself from the president. A complex position considering that the government currently receives harsh criticism for the crisis in the health system or for the recent military bombings in the Amazon region of Colombia in which minors were killed.

He, for his part, has been asked to condemn the president more harshly for the deaths of minors, as he did in the right-wing government of Ivan Duque. Cepeda spoke out, albeit more vehemently, against the forced recruitment of armed groups. “As I have done in the past, I reiterate my position that actions of this nature are clearly prohibited under international humanitarian law. Likewise, I strongly condemn the recruitment of children and the actions of dissident armed groups,” he said on his social networks.

His first public act in Bogota was in line with his political personality: measured and prudent. This restraint clearly distinguishes him from the president, who has been more impulsive in his speeches, tweets and decisions. But calm, although an advantage in almost all areas, is usually not an easy political capital to exploit during electoral periods, when the winner is usually the one who best moves the emotions of the electorate.

Dozens of people with purple flags, bearing his name, then surrounded him; yellow, alluding to the Polo Democrático, his party; and white with the logo of the Historical Pact, the community created by Gustavo Petro and which has its legal position pending before the National Electoral Council just under a month after the closing of the registration of candidates for the Congress of the Republic. This is the other great challenge that Cepeda’s campaign must launch, more legal than political.

“The Historical Pact is the strongest and most influential political formation in Colombia and, therefore, it is not possible at this point that the CNE persists in not wanting to give us our legal status,” the candidate said in Bogotá. Cepeda announced that she had filed a conservatorship to resolve her situation, but also sought to encourage her followers in case she was not recognized. “We will assert our legitimate right to political participation through legal channels and on the streets, through peaceful mobilization,” he announced.

The uncertainty over the legal status intersects with another front: Cepeda’s future in the Frente Amplio, a broader consultation scheduled for March with other progressive candidates, with the aim of winning votes more in the center. Their participation in this mechanism depends on the Registry Office’s decision as to whether the recent consultation was inter-partisan or not. If it is, you may be barred from racing again. This decision is fundamental for redefining progressivism, since not only the presence of the senator in the next internal competition depends on it, but also the formation of the lists and the agreements between the different political sectors that today try to arrive with a single candidate in the elections.

Until before the public event, Ivan Cepeda’s campaign was less visible. A week after winning the consultation, he appointed María José Pizarro, a more media-friendly and race-ready politician, as head of debate. In an interview with RTVC, Pizarro said his strategy is to “make people fall in love with our ideas.” Within the Covenant, his arrival was interpreted as an effort to organize the campaign, give it a greater territorial presence and achieve a more recognizable narrative.

Cepeda and Pizarro are united by a harmony that transcends politics: both are children of the violence that devastated the country in the late ’80s and early ’90s. He is the son of Senator Manuel Cepeda Vargas, murdered in 1994 in the extermination against the Patriotic Union; She is the daughter of M-19 commander Carlos Pizarro Leongómez, who was assassinated in 1990 during his presidential campaign. This shared experience, which marked their public paths, became a point of affinity in the campaign and a way to underline the need to insist on an agenda of peace and political guarantees.

A week before their meeting in Bogota, Cepeda had conducted another public event in the small square of the Cathedral of Pasto, the capital of Nariño. “Here we have the duty to win the elections in 2026. There will be no more crimes against humanity. We are not afraid of electoral fraud,” he said in his speech on a rostrum. With a packed street in one of the electoral bastions of progressivism in southern Colombia, the senator sought to reassert his leadership outside Bogota. The event also served to strengthen support for the region’s indigenous and peasant organizations, which have been instrumental in the mobilizations that have accompanied Petrism in recent years. In this scenario, he insisted that his campaign will visit areas where the government maintains its support, but also those where discontent has grown, with the aim, as he said, of “listening, correcting and building agreements”.

Along the same lines, Cepeda sought to demonstrate that his proposal for a national agreement does not aim to stagnate the political debate, but rather to establish a minimum basis of consensus. He also said that this mechanism must be defined with actors who do not necessarily share the progressivism agenda, an idea similar to the one Petro launched four years ago, but which fell apart shortly after he was elected. With an electoral campaign having just begun for him, the person chosen to succeed Petro in the Nariño Chamber finds himself faced with the need to make space for himself with a continuous and not very daring proposal that must win over the less radical sectors of the left and center.