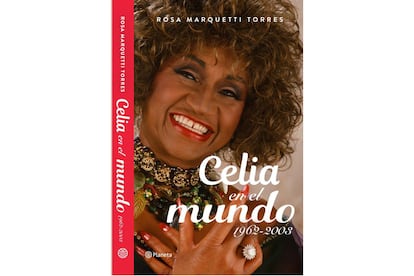

She is not – and she makes this clear, as if she didn’t want to take credit for something so great – Celia Cruz’s biographer, but she knows her like few others. After immersing herself for eight years in her personal and professional history, the philologist and musicographer Rosa Marquetti has written two volumes on who is, without a doubt, the most universal Cuban singer. Three years ago he published Celia in Cuba (1925-1962)a tour of his time on the island, where Marquetti was also born. But there was much more to tell, and last month it was launched on the publishing market, edited by Planeta, Celia in the world (1962-2003), the book that tells the story of the artist’s life from when in 1960 he boarded – unknowingly – on a plane of no return to Mexico, together with the group La Sonora Matancera, until his death, which occurred at the age of 78, on the banks of the Hudson River in New Jersey.

If you ask Marquetti to say something that almost no one knows about the singer, or what she discovered only by snooping through Cruz’s “impressive personal archive”, to which her executor, Omer Pardillo, gave her access, she replies: “I never knew before what Celia had to suffer when she decided to release one of her biggest hits of all time.” When the guaracha sang Isadorasong by the Puerto Rican salsa singer Tite Curet dedicated to the dancer Isadora Duncan, Cruz was the target of a “campaign of cancellation and political lynching”, starting “from the hard lines of the Cuban exile in Miami and New York”, says Marquetti. Duncan sympathized with the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, so by singing for the dancer “he transformed Celia into a communist traitor. I discovered this by investigating his archive. He kept, annotated, newspaper clippings.”

The singer’s body has always been hit by the sledgehammer of politics. The biggest blow was dealt to him by Fidel Castro’s government, denying him permission to enter Cuba to attend his mother’s funeral in 1962, just three years after the Revolution. “It marked a watershed in his relationship with the Cuban government, but not with his country, homeland and nation. He always defended his Cuban identity with an impressive sense of belonging and acted accordingly, with a sort of explicit maroonage,” says Marquetti. “Unintentionally, Celia has become a representation of the extreme tensions between the government in Havana and the Cuban communities established in Florida, New York and New Jersey.”

One hundred years after her birth, Castroism does not forgive the singer for having become Celia Cruz. A work that the National Ballet of Cuba was supposed to premiere as part of the artist’s centenary celebrations was recently cancelled, as was the show that the theater group El Público intended to present in the space of the Fábrica de Arte Cubano (FAC). Her audience on the island claims her, on the individual altar of all her beliefs. Even outside the country. On November 22, Marquetti presented her second text at the Miami Book Fair, in front of people who still applauded her.

Ask. Was it the secrecy and obscurantism around Celia Cruz in Cuba that made you want to look for her?

Answer. I was always interested in learning more about musicians who had been eradicated from Cuban culture by political censorship. That interest led me to endless listening and reading, and along that path, I came across some opinions from non-Cuban colleagues and journalists who vehemently claimed that Celia was “created” by the great Dominican musician Johnny Pacheco. This statement ignored Celia’s brilliant career in Cuba, her early years of education, development and rise, all of which occurred in her home country. What was best known about Celia internationally was her triumphant period in New York, starting with the salsa movement of the seventies, but little or none of the above was widespread. Writing a book, placing Celia in her respective contexts, became a necessity. It awakened in me a feeling of curiosity and also of justice.

Q. Who is Celia beyond the cry of “Azúcar!”?

R. I went from amazement to deep admiration as I delved into his life, career and personality. However, certain stereotypes born from love for her in some cases, and in others from a hatred born from politics, have been, in my opinion, an obstacle to the complete knowledge of Celia that I wanted to share with my readers. Celia is her extraordinary voice and savoir-faire, her genuine grace, her wigs, her flat shoes, the one shouting “Azúcar!”, the one with Life is a carnival, Quimbara, Bemba Colorá AND The black woman has a tumbao. But Celia is also “La Guarachera de Cuba”, the one who expanded towards other musical genres that were not hers, the one with 60 years of an impressive career, the one who has traveled the world, the Cuban patriot, humane, very hardworking, extraordinarily simple and, at the same time, skilled in her public projection. Very intelligent and shrewd in leading her career, because she made the crucial decisions, to the point of convincing her managers of something and that life then proved him right, as in the case of the inclusion of Quimbara in his repertoire, which Jerry Masucci initially thought of opposing. Celia is much more than “Sugar!”, but she has made that word an effective advertising resource and an irreplaceable sign of identity.

Q. What did it mean for the artist to leave his country?

R. Celia did not leave Cuba. The rapid development of political events between the country and the United States between 1960 and 1961 meant that many musicians decided not to return. Adding to the unstable situation in Cuba was the promulgation, on December 5, 1961, of the law that established permission to enter and exit the country as a prerogative of the nascent Ministry of the Interior, declaring those who did not return within the established deadline before the end of the year as traitors. All this triggered panic and many decided not to return, including Celia. When he left Cuba on July 15, 1960, he didn’t know he would never return. Every change in someone’s life generates other changes. Even in Celia, as her career from 1970 onwards experienced extraordinary growth and her life had to adapt to the new and promising reality. Celia keeps up with the times, always renewing herself, without altering the backbone of her art: the essence of Cuban popular music. But in substance, in her personality, in her character, in the beliefs of those who were close to her and in her own declarations, they attest that she has remained the same.

Q. In his new book he interviews artists such as Rubén Blades, Willie Colón, Willy Chirino, Paquito D’ Rivera, the Estefans and Chucho Valdés, some of the singer’s colleagues in the Fania All Stars. How do you see Celia?

R. Everyone agrees on Celia’s greatness as a voice and expression of our music. In his talent, in his human condition, in the particularities of bilateral treatment, on a personal and professional level. It was amazing to me that all of them agreed to my interviews. It was so important to get so many looks from so many personal angles, so many expressions of appreciation and respect for Celia.

Q. What caught your attention most of all the material you consulted for your books?

R. Over the course of her life, Celia built an impressive personal archive. It was common for artists of their time to compile scrapbooks of newspaper clippings in which they were mentioned, as well as photo albums illustrating their careers. Celia’s are tremendously complete. In my second book, as in the first, I worked a lot with the press of the time. I was able to benefit from the widespread digitization and availability of newspapers and magazines in the United States and in the countries where Celia sang, but many others I could only consult in scrapbooks of the artist. This second book places emphasis on the perspective of others – fellow musicians, journalists, critics, intellectuals, friends, staff – to construct the life path and interpretive work, and the image of Celia herself.

Q. What was Celia’s great contribution to Latin music and salsa in particular, especially in New York?

R. The history of the extraordinary New York salsa scene of the 1970s cannot be written without putting Celia Cruz’s name in prominent letters. She was the only woman on the initial roster of Fania Records and Fania All Stars. Among all those young and handsome guys, she was the only one who came with an established professional career, with enough experience and knowledge of the industry. But what his voice, his style and his authentic and radical art contributed was, in my opinion, his greatest contribution to the salsa movement in New York. In 1988, on the occasion of the 30th edition of the Grammy Awards, part of the gala was dedicated to the music of the city. On a stage where Whitney Houston sang her big hit I want to dance with someone, and Billy Joel intoned New York state of mindthose chosen to represent the big city Latin sound were Celia Cruz and Tito Puente, who performed Quimbara. This fact could not be more significant. Celia’s great contribution to Latin culture was the defense of the fundamental genres of Cuban music: guaracha, son, rumba, bolero. And its ability to conquer new audiences, new generations, new geographies, always renewing them to bring them closer to the acceptance of these audiences.

Q. He said previously that in Cuba “they have been afraid” of Celia’s voice for 60 years.

R. I was hoping that something would change for the better on the occasion of the centenary. But I was wrong. There is no valid argument to support the contempt and vicious and cruel attack against a figure of whom the leaders of Cuban culture should be proud. The facts have been hyperbolized around Celia and her dissent against the Cuban government and a macabre narrative has been constructed, the truth and certainty of which until now has never been proven. The Celia that we Cubans have lost cannot be replaced by her demonization. My second book reflects his relationship with Cuba and records the facts and actions I encountered that supported his position towards the government.

Q. Why wasn’t there a truce with the singer?

R. A government cannot usurp the concept of homeland, nor that of nation, nor that of country. It is impossible for them to simultaneously address the world’s recognition of what Celia is and represents, and her anti-Castro position, and articulate a coherent, inclusive, respectful and high-minded position that takes into account the impact of Celia’s legacy on the various generations that make up the Cuban people. I always like to talk about the mark that political censorship leaves on the bodies and spirituality of censored musicians and creators. We don’t usually talk about it, but it’s there, and it was more than evident in Celia: she was never able to truly recover from such grievances.