The prestigious medievalist Bernard Guenée said from his chair at the Sorbonne that every medievalist knows that the Middle Ages never existed, because who would dream of putting the men and women and the institutions of the 7th, 11th and 14th centuries in the same bag? In our collective imagination, the Middle Ages were a period of poverty, famine, plagues, abuses of lords against peasants and corruption of the clergy. From that imagined and imaginary Middle Ages we only save the tournaments and court life, the knights and princesses, the witches and fairies, a magnanimous prince and some cultured monks committed to the people in the face of the hypocrisies and simonies of the Church. The Middle Ages was born from the contempt of the Renaissance, of Petrarch for example, conceived as a dark and theocentric era unfortunately interposed between classical antiquity and its bright anthropocentric present, albeit from Romanticism, as Chateaubriand in The genius of Christianityin it we saw the legitimizing origin of national traditions and identities. Regardless of the inventions of the prefabricated past, there is no doubt that Lessing was right when from the Sturm und Drang he shouted: “Middle Ages night, yes! But a night shining with stars!”

In Medieval bodies. Life, death and art in the Middle Ageshistorian Jack Hartnell guides us into that medieval territory through an atlas of anatomy, from head to toe, combining art, medicine and theology and showing that in the Middle Ages the body also counted, that it was much more than anatomy, and that it was also the mirror of the soul.

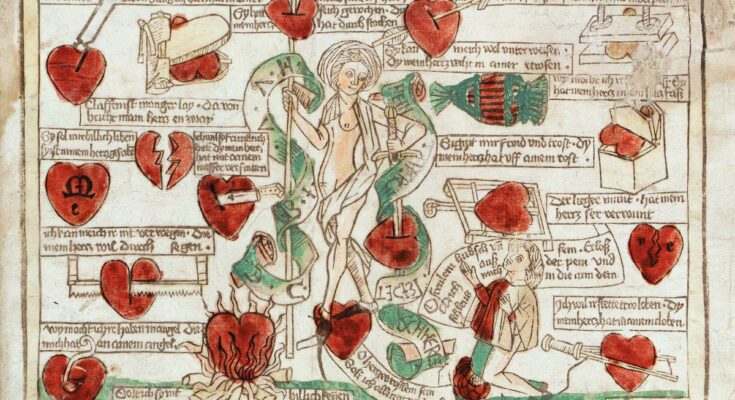

Dismantling the cliché of the dark, credulous and superstitious Middle Ages and presenting it as an era with its own brilliant light like Antiquity or the Renaissance is not a new challenge, but the restoration of that mistreated era of history in our imagination is still necessary for the reader or non-specialist public. The men and women of the Middle Ages suffered and died, but they loved and grew old, their world was not harsh and inhospitable and they did not live only in swamps full of mice or in sunny palaces to the sound of troubadour music. In every gesture of that universe, the physical and the spiritual touched each other and the body was a microcosm that showed itself as an imperfect replica of the divine, as a theater of the coercion of desire and the desires and fears of the spirit.

Hartnell’s journey through medieval medicine and the history of its art is an equally legitimate way of thinking and writing history, without forgetting that disclosure and curiosity should never be incompatible with the rigor of the researcher, much less with the agile and didactic style with which he tells us that history. As an art historian, he shows us how medieval medical treatises were also a catalog of paintings and reliquaries, tapestries and frescoes, tombstones and scenes carved on church doors that represented effigies of life and death, health and illness, fasting and feasting, the bowels under the skin and heart disorders. In each chapter an area of the body is explored and a narrative and profusely illustrated anatomy is intertwined with a cultural history of the body, from East to West, from Christian Europe to the Islamic world, without ever succumbing to transforming the Middle Ages into a museum of oddities and monstrosities. It is true that sometimes little is explored about the gender perspective and the difference between the male and female body, the symbolic construction of motherhood or the role of women in medicine and care beyond the sexuality of the second sex. Too often the poor, i laboratories so present in the sources and in daily life and so absent until the advent of the Annales School, before the kings (bellatores), saints or martyrs (speakers) who structured the three orders of the medieval feudal imagination, as the great Georges Duby taught us.

Even so, the pages of medieval bodies They shed light on a time that we usually imagine in darkness and darkness, a story that Abada gives us in a careful and beautiful edition that can be read not only with the eyes but also with the touch, with the memory of the senses, which certainly was not ours in the Middle Ages. The story of the beautiful and sinister fragility of vulnerable bodies transcends the skin on every page, although the miracle never hides the knowledge of the medicine of yore that healed not only the ailments of the soul, but also, and not infrequently effectively, the ailments of medieval bodies.

Medieval bodies. Life, death and art in the Middle Ages

Jack Hartnell

Translation by Miguel Ángel Martínez-Cabeza

Abada Editore, 2025

348 pages, 38 euros