The architectural competition for the Cuelgamuros Memorial was unsuccessful and, in my opinion, the winner is a wonderful project. Very sensitive and very delicate, especially when the premise was so complex. Why? Essentially because stone preserves memory better than men. Not because he possesses a mineral form of consciousness, but because he has no choice: he remains.

When we look at the stone of the Cuelgamuros Valley – a name that still vibrates with the echo of the previous one, as if it had to be pronounced twice for it to fully settle – the impression is of something that was there long before our arrival and that will remain there long after. The stone has seen speeches, silences, celebrations, protests, escapes, prayers, tourist photos, and even those years in which no one knew exactly how to look at this place without the gesture being loaded with immediate political meaning. The stone remains there, immobile and patient, with the only apparent function of remembering what human centuries have missed.

For decades it was the Valley of the Fallen, the great post-war monument, first conceived to honor the dead of the Franco front and only later invested with the aspiration, or perhaps the rhetorical intent, of representing a national reconciliation that was never achieved. That idea of reconciliation was always shrouded in a semantic fog: it was said, it was repeated, but it rarely materialized into something tangible. Only the architecture of the complex seemed to set the conditions for that conciliation. Forgiveness could only be granted from above and not constructed between equals. Meanwhile, on the other side of history, among those who actually built everything – pickaxe, shovel, dynamite, cold, endless days – there were also hundreds of republican prisoners integrated into the penal detachments. Their names remained in the files, on the payroll, in the administrative notes, but their efforts remained here, fixed in the rock, in the excavated vault, in the very consistency of the granite. An involuntary but persistent inscription.

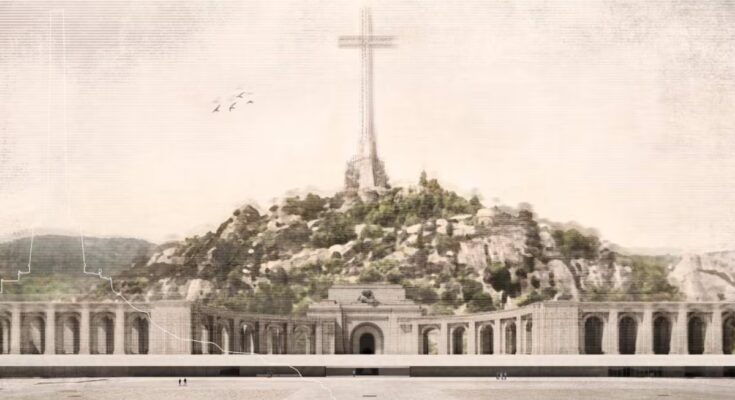

The complex, with its one hundred and fifty meter cross and its basilica that pierces the mountain, wanted to express permanence and transcendence from a very specific aesthetic – the national-Catholic one, the military one, the rectilinear and severe monumentality of the first Francoist era – which gave everything a tone of vertical magniloquence, a type of architecture that spoke above the visitor, not with him. For years the valley functioned as a symbol that wanted to be univocal but which, in practice, accumulated overlapping meanings: victory, mourning, propaganda, religious architecture, sacrifice, silence, absence of those who were not represented there. As time passed, that same materiality – the stone, the mountain, the void carved into the rock – began to transform into something else: an uncomfortable mirror where the present tries to understand what to do with a past that continues, in some way, to vibrate beneath the surface.

And that complexity – made up of trampled layers, of memories that don’t fit together, of silences that weigh more than some words – made it clear that it was necessary to rethink the place. Don’t rewrite it, because history doesn’t allow infinite drafts, but give it new meaning: open it, contextualize it, let it be read without one-way filters. For this reason, an international architecture competition was announced. The idea was not – or should not have been – to erect a counter-monument, but rather to seek an intervention capable of listening to what the valley was already saying. Listen to all the stories involved – even those that had been silenced – and offer a framework in which that plurality could be understood without being obscured.

The winners of the competition are the architects Carlos Pereda and Óscar Pérez, together with the company Lignum. Your proposal, The base and the crossit seems to arise from an extremely careful reading of the place, from primary attention to the mountain before drawing the first line. And what, in my opinion, they achieve is something that could be defined as a healing operation: not to erase the monumentality – because to do so would mean, in some way, amputating the memory – but to reorganize it, move it delicately, so that it can be read from another place, from another emotional tone. The project is deliberately delicate, almost reticent, as if it were aware that every architectural gesture here weighs more than in other places because it intervenes in a place full of historical tensions.

The intervention is structured around a clear gesture: the old monumental staircase disappears and a horizontal platform appears in its place. This gesture, which might seem technical or functional, is actually the beginning of a profound transformation. Where previously the visitor ascended on a path that reinforced solemnity – a literal and symbolic ascent – they now enter at ground level, without forced rituals. Access becomes more civil, more everyday, more in line with a present that does not need to reaffirm the verticality of authority to relate to one’s own memory. Architecture lowers the voice, lowers the tone, and in that lowering, a form of unexpected relief occurs.

This horizontal porch functions as a continuous line that accompanies the landscape. In the project drawings the Sierra de Guadarrama occupies more space than the architecture; The valley recovers its status as a valley, and architecture accepts something that it did not fully admit for decades: that it is not the only protagonist. Monumentality becomes porous, modulated, attenuated. It does not disappear – it would be impossible – but integrates into the environment in a new way, renouncing the imposition of a single symbolic gesture. The arrival is no longer an act of elevation, but a calm crossing between outside and inside, a transition that is more interpretative than ceremonial.

At the center of that platform appears a large circle carved into the slab, a void that allows you to see the sky. This void works almost like an emotional decompression chamber: a place in which to locate oneself, look, understand or even not yet understand but have the necessary space to do so. In a context where everything has been so charged, so dense, so programmed, what an empty space can mean is, in itself, a powerful gesture.

Below the platform, a large shadow welcomes the beginning of the museum itinerary. That shadow – an in-between space, a physical and emotional ancestor – serves as a narrative threshold. The history of the valley unfolds there: its origins, its construction, the political context, the prisoners forced to work, the subsequent uses, the debates that have accompanied the place for decades. It is a space of limited dimensions, with clear environments, filtered light, sober materials. All designed not to compete with the pre-existence, but to support it from another angle.

Documents, photographs, objects, projections, fragments of history reconstruct a mosaic that does not aspire to unite excessively. There is no single message, because the valley cannot be reduced to just one. The architecture here acts almost like a tack: it unites without tightening, connects without forcing, lets the stories breathe.

The result is a new way of approaching the valley: more horizontal, more open, more aware of its complexity and history. Of its entire history. An architecture that does not try to solve the unsolvable, but rather offers a space where society can ask itself questions, some uncomfortable, others necessary, all inevitable if we want to look at the past without filters.

And perhaps – just perhaps – true resignation lies neither in the portico, nor in the club, nor in the museum rooms, but in the simplest gesture of the project: the will to listen. Ensuring that the stone continues to tell what it remembers, while allowing us, for the first time, to decide to listen to it differently.