EL PAÍS openly proposes the América Futura column for its daily and global informative contribution on sustainable development. If you want to support our journalism, subscribe Here.

“The conditions for living on the streets change depending on where you are in the world,” says Karinna Soto, a Chilean engineer and one of the most recognized voices in her country on homelessness, the situation of living on the streets or without a permanent home. “In many countries in the Global South, Latin America or Africa, it is much more difficult, because social support is very precarious,” he explains.

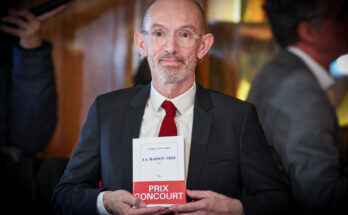

In Chile, Soto is co-founder of Corporación Nuestra Casa, an organization that offers shared housing and support to young people trying to get off the streets. He also directs Together for the Road, a network of organizations belonging to the Chilean alliance of the 3xi Corporation, the PCC and the Community of Solidarity Organizations. For over 25 years he has dedicated himself to the study, planning and support of public policies in favor of homeless people and this year he launched The land of carpa book that collects testimonies about street life in Chile.

Her career has taken her to travel across Latin America, live in Haiti, and work with organizations and governments to improve policies addressing homelessness in Uruguay, Costa Rica, Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia. Furthermore, it is part of the Institute of Global Homelessness, a global reference center for the eradication of homelessness. From this comparative perspective, he explains that, in the Northern Hemisphere, social safety nets reduce the chances of reaching this situation. “There are places where you can shower, receive psychological support and even access accommodation.”

This gap, he warns, widens in highly segregated, low-income Latin American cities, affected by drug trafficking, informal work and lack of access to housing. Added to this are the effects of climate change, which have pushed communities to lose their homes.

“The average person living on the streets in Latin America is a young person, between 43 and 47 years old, and has had children who were not in his or her care. Many have been poor since childhood and work every day, even if not in formal employment. Half continue to consume some substance, alcohol or otherwise, have a lower level of education and have acquired chronic illnesses, such as mental illnesses.”

“A snapshot of what countries have failed to solve”

However, Soto insists that the street situation does not respond only to personal trajectories. “It’s a snapshot of what countries haven’t been able to solve,” he explains. If in the United States they are war veterans and in Eastern Europe they are migrant workers, in Latin America, he indicates, they are young adults excluded from social policies. “Our social policy is very feminized: when a house falls apart, women are usually left with the house and children, while men are left without a net, moving from place to place to sleep.”

This profile, however, has diversified following unprecedented migration from Venezuela, Haiti and Central America, driven by political instability, lack of opportunities and rising costs of living. “Our countries are not prepared to welcome so many people. Many migrants end up in informal settlements, such as camps, or on the streets,” he says. At the same time, the street has begun to show another face: “Today we see more women: in Chile the latest census shows that almost 19% are women, ten points more than ten years ago.” This presence has grown due to the impact of drug use among young women.

The phenomenon, he continues, cannot be reduced to individual poverty: “The street is above all an urban problem. It reflects the gaps in access to housing, the lack of coordination of social policies and the profound inequality between territories of the same city”.

Fear the unknown

Karinna Soto grew up in Rancagua, a mining town located just over eighty kilometers from Santiago, and was raised by her maternal grandparents after her parents, teenagers, could not take care of her. “My grandfather had a difficult life in the South, like that of many indigenous children who quickly emigrated to a big city. He had to work on the streets and sometimes even lived on the streets,” he recalls. “From him I learned that no life is unfathomable, that despite the history it carries with it, it is possible to also carry other things with it: the value of hope, of family, of community.”

Years later, she realized that her story connected her to the homeless and gave her a way to understand them from the inside. Since then, his work in Nuestra Casa and Juntos en la calle has been guided by that first experience, which showed him how exclusion arises from the interweaving of family, social and economic fractures.

Ask. What does being on the street mean to you?

Answer. It’s more than just being homeless; This is just the tip of the iceberg. Being on the street means being hidden in plain sight; It is having chosen, on the one hand, and not having been able to choose anything else. It means exposing yourself to risks that today are deadly. In Latin American cities we have street violence, murders, hate crimes. You are more likely to die from an underlying disease. A manager from our organization showed a pack of antibiotics and said: “In Chile it costs two dollars, it’s worth avoiding a death on the street.” Most die from infections that would be treatable at home. But without a home you have no access to health, nor a place to recover. This is why the life expectancy of people on the streets is up to thirty years less.

Q. Why are there people who leave the streets and others who don’t?

R. It really depends on how long I’ve been there. The road deteriorates, explodes and kills: it is a universe of multiple risks. The more time you spend there, the harder it will be to go back. You don’t just lose your health: you lose trust, bonds, expectations. In Latin America there are men and women who have lived since childhood in contexts of poverty, lack of education, mistreatment, malnutrition, violence, even abuse and exploitation. When you see someone who is 30 years old on the street, many times they have spent 20 years immersed in exclusion. Nobody gets out of it in a day. Long-term support, stability and policies are needed.

Q. What solutions are urgent and possible?

R. We always talk about three keys: data, collaboration and housing. The first thing is to know who the people living on the streets are and what they need. The most effective solutions are community and neighborhood ones, in which public and private actors participate. No sector can solve it alone: a common table is needed between local state, social organizations and businesses. But nothing works without housing. Without a roof at your disposal, any effort has minimal impact. In Latin America many people could pay rent; This is why it is necessary for policies to include a fourth dimension: the direct participation of those living on the streets in their solutions. We can no longer generate vertical responses, knowing that there is a people who have a voice, strength, work and family. Leaving them out, as if they couldn’t collaborate, is a mistake. And that may be the most distinctive thing about what we do in the region compared to the world.

Q. What policies have been proven to work?

R. The most effective is called “Housing First”. In Chile, Uruguay, Brazil and Costa Rica we have been promoting it for years. Putting housing first, not last, saves enormous social costs. The traditional model, known as “staircase,” requires the person to go through certain stages, such as quitting drugs, finding a job, taking care of their health and then accessing housing. But you can’t ask someone to rehabilitate, get a job, or get healthy if they don’t have a place to sleep. Once you have a roof over your head you can think about the rest: hygiene, safety, connections, community.

Q. Why is it uncomfortable to see someone on the street?

R. We fear what we don’t know: we live in societies that have told us how bad the other or the stranger is, which have taught us to distrust what is outside our bars and to think that good only lives in what is intimate or known.

Q. Do you think it can change?

R. The new generations, and I see it in my son, are more open, less full of prejudices and with less rigid structures. I am confident that they will be able to build societies where we all have a place to live.