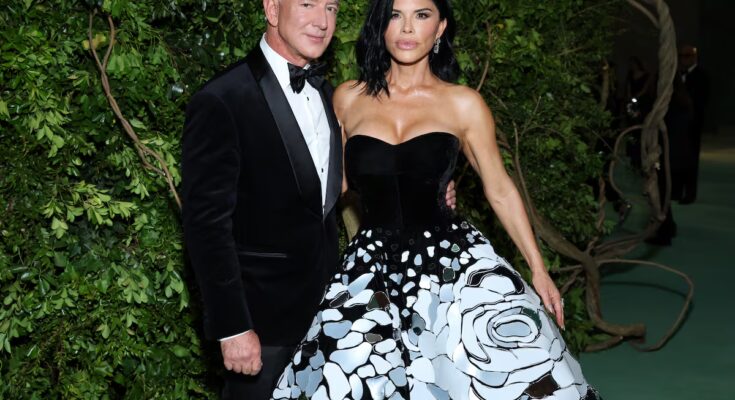

This year the Metropolitan Museum in New York inaugurates the Condé Nast galleries, more than a thousand square meters sponsored by the lifestyle publisher that will host fashion exhibitions. To celebrate the opening, the Museum’s curator of clothing, Andrew Bolton, announced that the MET’s annual exhibition will be titled Art of costume and will focus on the idea of the dressed body throughout history, a theme perhaps too broad for which more details are not yet known, such as what the dress code the guests of the opening gala will have to follow. What is known, as stated in the museum’s press release, is that this gala “is possible thanks to Jeff and Lauren Bezos”. Not to Amazon, but to the couple themselves, who together with Anna Wintour will have the task of acting as hosts and selecting the guest list.

Until now, luxury brands were responsible for sponsoring the event. For this reason, many of the participants in the great fashion gala dressed in, among others, Louis Vuitton or Loewe, sponsoring the respective events. This year will be different. Although Saint Laurent is responsible for financing the exhibition catalogue, the Bezoses will decide who will have a seat at the table. “I imagine the couture dresses arriving in cardboard boxes from Amazon, the carpet broadcast on Prime or the celebrities arriving on Blue Origin,” they write in an editorial on The Independentwhere it is also remembered that Bezos donated through Ground Fund more than six million dollars to the CFDA (Council of American Designers) to promote an innovation and sustainability program (apparently, without irony).

It’s not that the third richest man in the world is trying to control public opinion (he already has the Washington Post), the algorithm or even the space race; It’s about trying to control something as seemingly banal as taste, a category historically used to draw social boundaries.

To talk about the social dynamics of taste we must continue to resort to Pierre Bourdieu’s essay, ‘Distinction’ (1979), which defines it as an abstract criterion that is modeled through the lifestyles of certain social classes. Although there are exceptions, economic, educational and cultural capital accumulates in an almost correlative way: the money and possibilities (both economic and social) of the upper classes give access to education and a type of culture that makes them guarantors of taste. For Bourdieu the perfect example is art: knowing art and, obviously, knowing how to buy it. But his theories on taste as a criterion for classifying the upper classes were and are perfectly applicable to fashion. Indeed, if the large luxury companies did anything at the beginning of the century (Prada, Kering, LVMH…) it was to open foundations and/or museums to legitimize themselves as arbiters of taste.

It is no coincidence that we frown upon those characters who embody the category of the nouveau riche. The idea that you have good taste or you don’t, that is, that it’s almost innate, has historically been propagated by those born into privilege. When we accuse someone of being “tacky”, whether they are a tycoon or not, we are validating that idea of taste as something natural, typical of those who know how to surround themselves with beautiful objects and do not need to signal status through what they own. This is why, specifically, the idea of silent luxury has made its fortune in recent years, the subtext of which seems to say: “those who have really good taste don’t shout with their clothes, they whisper so that only others like them can hear it”.

Now this “newcomer” image is embodied by Bezos and Sánchez. It is a questionable image, since to criticize any public figure, even a tycoon, for being in bad taste, that is, for having bad taste, is actually tacitly agreeing with these social theories about class, cultural capital and the existence of a language of beauty that only natives speak. The problem, however, comes when the couple does not want to have good taste, but rather buy the “means of production” that propagates it.

Not long ago, and above all, those who believe they are guarantors of good taste, raised their hands when Kim Kardashian and Kanye West began to sit in the front row at Parisian fashion shows, a strategy that culminated in 2014 with both wedding dresses on the cover of Vogue, the great legitimizer in terms of social and aesthetic prescription. A sort of rite of passage that the Bezos have also completed. Last September, they both attended the Balenciaga and Chanel fashion shows and, months earlier, Lauren had appeared on a controversial cover of the same magazine revealing her wedding dress, designed by Dolce & Gabbana. The report was signed by Chloé Malle, then lifestyle editor and now successor to Anna Wintour as content director of the North American newspaper.

Many things, good and bad, can be said about Kim Kardashian, but few would say that she embodies the epitome of bad taste or bad taste. Brands stand out for dressing her up or inviting her to their events. The Vogue cover was the first step towards cleaning up her image. Another great tacky girl from the past, Victoria Beckham, years ago created one of those quiet luxury brands to demonstrate, with moderate success, that she was much more than the spouse of a football star who voraciously consumed logos and trends. It’s not that they learned to have good taste; They have learned to manage the symbols that define it.

“They no longer know what to do to buy cultural capital; the closer they get, the further they move away,” wrote Lucía Levy, founder of the podcast and Instagram account ‘La Curve de la moda’, one of the most listened to Spanish-language fashion programs, after the MET announcement. The truth is, you can’t blame the Bezos for not rigorously following all the classical steps in their rise to ‘good taste’: they bought Venice for a few days to celebrate a wedding full of celebrities and Haute Couture gowns. Then the cover of Vogue, now the MET gala, and in between, Lauren Sánchez wore the kind of ridiculous bag (by Balenciaga) that only women would wear. influencers (or the famous ones with an influencer vocation) and walked around Paris with two archive outfits: a Bar jacket from the Galliano era by Dior in 1995 and a two-tone Chanel dress from the same year. The archive is the tool that celebrities use today to demonstrate that they know fashion. Kim Kardashian, in fact, is the expert in dusting off outfits from the pre-social media era at a time when industry fans applaud these bursts of nostalgia because they believe that what was designed before social media is more authentic. The paradox of viralizing what has escaped virality. Galliano’s pantsuit earned a large article in Vogue dedicated to Sánchez’s stylist, Molly Dickson, who also dresses Sydney Sweeney.

There have long been rumors that Bezos wants to buy Condé Nast from his wife. And the MET matter is now believed to have been her request, based on that rhetoric suggesting she “brainwashed” the third richest man in the world as if he were incapable of making his own decisions. In reality they are not billionaire whims. They are strategic moves by someone who has understood that, in the contemporary cultural ecosystem, power is not just about controlling infrastructure, media or technologies, but also about managing the symbols that define what we consider aspirational or beautiful. Legitimize yourself with a checkbook as a prescriber. Don’t just sit at the table of the most viral charity gala there is, but decide who sits there.

The strategy is not new at all. Long ago, the great fortunes, in an attempt to acquire those typical codes of the aristocracy, began to buy wings of famous museums or donate their collections. The Rothschilds, the Rockefellers and even the Sacklers, the pharmaceutical saga that created unfathomable chaos with the marketing of oxycodone. In 2021, the families of the deceased managed to convince the MET to remove the name from one of its wings.

That’s why the issue isn’t whether or not marriage will be able to cleanse its image, which it will. Because the problem is that money can buy everything. Even the idea of good taste, although, paradoxically, those who have money have been telling us for years that good taste cannot be bought. In fact, it doesn’t matter how they dress, because they can market any idea, including dressing well. And this also shows that taste is a fiction that those who can afford it manage as they want.