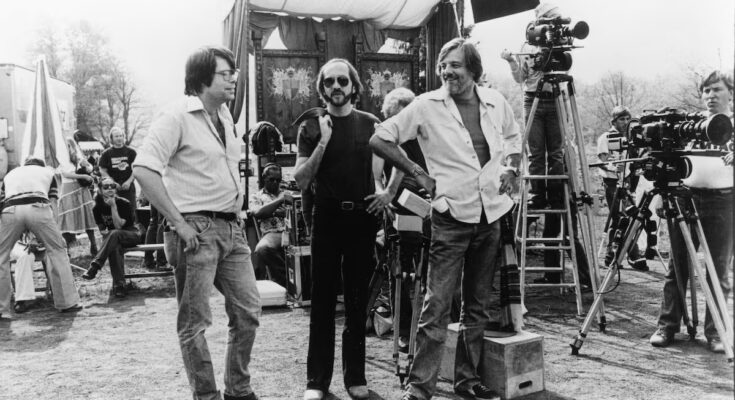

In the last four weeks, three films based on novels or short stories by Stephen King have been released in commercial theaters. In the last month, two series have arrived on digital platforms, also inspired by texts by the American writer. And at the beginning of 2026 another one will appear, and not just any one: the series Carrie, with director Mike Flanagan behind it. A look at IMDb’s digital movie database is scary: since 1976, when the original film came out Carrie, by Brian de Palma, more than 400 audiovisual productions have been created with the name of Stephen King behind them. There is no other living writer so covered on screen (and he is second in history after William Shakespeare, with 1,876 produced based on his works). What is it about Stephen King, author of more than sixty novels and two hundred short stories, that makes him so attractive? What do directors and experts think of this wave of adaptations?

A month ago the exceptional The Life of Chuck with which Flanagan once again demonstrated his talent in suspense, both in its drift towards terror and in its fantasy aspect. It is not the first time that the filmmaker, an undisputed figure of these genres both in cinema and in series, has attempted to adapt a text by King: he has already done so in Gerald’s Game (2017) and in Doctor Sleep (2019), continuation of The glow.

The Life of Chuck belongs to the King who mixes fantasy and nostalgia, like the one previously adapted Hearts in Atlantis, The Green Mile OR Life sentence. Flanagan, who is now in full production on the series Carrie, explained last summer in the United States: “It’s often assumed that Stephen King is a horror writer. I don’t think that’s true.” And he explained: “At heart, he is an optimist, a humanist, deeply empathetic and, honestly, very true to his principles. That his stories can be terrifying is secondary to these goals. For me, this is true whether we are talking about The Life of Chuck which I consider one of his most sincere and optimistic stories, starting from life sentence, which is just great, o animal cemetery, “One of the scariest stories I’ve ever read in my life.”

animal cemetery unites two Spanish directors, Juan Carlos Fresnadillo and Rodrigo Cortés, both with a lot of experience in the field of suspense and horror. Fresnadillo recalls: “I was fascinated by it when I was very young animal cemetery, my absolute favorite (referring to the 1989 version), and in fact I resurrected the project for Paramount in 2015 which in the end, due to those infernal development things in Hollywood, I couldn’t make it happen due to scheduling problems.” Cortés’ legs still tremble remembering reading the original novel: “I’ve been reading King since I was a teenager. I deflowered myself with animal cemetery, I still haven’t completely forgotten little Gage’s death. I have an urge to see some of the films born from its pages, perhaps as a way to revisit its landscapes or to discover what others have imagined. Most of them are fungible, shoddy, extremely warped or televisual material, which forgets that King is above all a writer of manners and characters.”

This reflection is made by several experts. In the preface to his book Stephen King (Editorial Lunwerg), who compares novels and film adaptations, Matthieu Rostac reflects: “According to many, King is a ‘badly’ adapted novelist, a man whose work is painstakingly destroyed by the film industry, which effectively turns his writings into safe values. They are not wrong (…) even if “King owes a lot to cinema, in the same way that horror films owe a lot to him”.

Director Carlota Pereda, whose Little pig (2022) was classified by EL PAÍS critic Elsa Fernández-Santos as “Carrie in Extremadura”, agrees along these lines: “I am interested in that cinema, especially when films move away from their texts. King creates relatable characters with relatable conflicts in a universe you believe is true… where strange stories happen. That’s why films that rely less on terror and focus more on everyday life are also better.”

Fresnadillo emphasizes, like Pereda, that it suits him a lot thanks to “his characters”. And he develops: “The external torment, the terror of the houses or the situations it poses arise from an internal fracture in its protagonists. From something that is not fully accepted or from a traumatic wound which, although buried over time, sooner or later will end up resurfacing”.

Cortés analyzes his adaptations: “There are class A films, like The Shining, Carrie, Misery OR Life sentenceand films made with great skill and sense of genre, like the same animal cemetery (the original), Cujo, Thinner… I, for example, am a big supporter of The dream catcher. Mand he likes it The fog, count on me, parts of Creepshow… Of the recent ones, I saw them with pleasure The Life of Chuck and I confess that I have always fantasized about adaptation The long marchwhich Francis Lawrence just shot successfully and some moments survived, albeit without leaving any scars. sin of flashback, It’s a shame about the ending.” Pereda underlines: “It adds nothing to the text, it’s superficial. I will always watch one by King though, because he himself is an IP, he fulfills the commandment of taking you into a world you already know and enjoyed at a given moment.

The long march It premiered last week, with Cooper Hoffman (son of Philip Seymour) as the protagonist, and too united, even in the coincidence of its director, in its theme with the universe The Hunger Games. Cortés continues: “I read that novel almost simultaneously The running man both written by King under the pen name Richard Bachman,” which is exactly the book King’s premiere this Friday is based on. The running man It is directed by Edgar Wright, who manages neither to give verve to the plot nor to make his main actor, Glen Powell, forget Arnold Schwarzenegger, protagonist of the first version of that novel in 1987: Persecuted.

Since Stephen King was hit by a minivan on a rural road near his home in his home state of Maine in 1999, the author has been unable to physically recover. You have reduced your working hours; In return, it has multiplied its digital activity, becoming one of the great prescribers of The dining room table, of Caye Casas. “For me there was a before and an after,” Casas acknowledges with a laugh. “King is the king of terror in the full sense of the word terror. From paranormal events to everyday ones, because he talks about families, about things that can happen to each of us and, without censorship, destroying taboos”, he underlines. “And with this he has won legions of followers: this is why platforms and production companies know that just by putting his name, millions of followers will be interested in their product. Look what happened to me.”

This is why King is also the seed of numerous series: in the summer it arrived on Prime Video The institute. “The most complicated thing about adapting a Stephen King story is that he is a wonderful writer of the inner lives of his characters. You can access their darkest, deepest and most secret feelings, emotions and desires. You can do it very well in a book, but it is a challenge how to externalize them on the screen,” his screenwriter, Benjamin Cavell, told EL PAÍS. The director of The institute, Jack Bender was also responsible Mister Mercedes (2017-2019), which Netflix just picked up, and he’s friends with King, so he can explain why he allows his work to be adapted so easily: “He really understands the process of making a series or a movie from a book.”

The other great explosion of platforms is carried forward by the universe of the city of Derry, where the clown Pennywise, the villain of the novel, does his thing every 27 years. Item. The Argentine brothers Andy and Bárbara Muschietti have already addressed the book in two films released in 2017 and 2019, and they themselves proposed to HBO En: Welcome to Derrywhose first season, of the three planned, is now premiering on the platform. “King is compelling because everything about him has a connection to social reality. They are criticisms covered by a veneer of fiction and terror. But we all recognize ourselves,” Bárbara Muschietti explained to EL PAÍS last month. For the producer and screenwriter, “Derry looks like any town, city, country at this moment in which unfortunately we live in such a global world. Because the waves of fear and fakism They are present all over the world.” Or as his brother pointed out: “Fear is the order of the day. It’s subtextual, but also quite literal.” King will be the great narrator of a somewhat idealized rural America, but at the same time he led the intellectual opposition against Trump. As Casas points out, “it gives him a hard time even in X, a territory allied with the president.”

Journalist María Gómez is such a fan of King that last Halloween she dressed up as Carrie and the day before as the girls from The glow. “Curiously, he doesn’t like that film”, recalls the journalist. “In fact, he hates almost all of its adaptations. I don’t understand why you don’t check out those movies and series more. It won’t be for money. And above all he gets very angry when the endings change. Why don’t you oppose it?” Gómez also highlights his author’s characters. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a child, a destroyed mother, a writer in crisis like him or a clown… They all have a perfect mix, which makes them brutal and memorable, of darkness and tenderness,” he reflects. And he insists: “More than a horror writer, he’s a life writer, because he handles a concept very well: what can actually happen to you is scarier than a monster. The most disturbing thing is in everyday life.”