A few weeks ago, songbirds began to be captured and ringed in different parts of Andalusia as part of a study funded with 14,800 euros (excl. VAT) by the Government to promote the “feasibility” of sylvestrism, a hobby dedicated to caring for species such as goldfinches, linnets or greenfinches – of the finch family – in cages and training them to shape their song and even compete in competitions. The biggest controversy arose due to the alleged scientific support of this research by the University of Alcalá (Madrid), since the author of the study is Pablo Luis López, a telecommunications engineer of this academic entity. López has a long family tradition of wildlife hunting (before him there were also his father, his grandfather and his great-grandfather), he was a delegate of the Madrid Hunting Federation and was awarded in 2023 by hunters for his work in the field of wildlife hunting.

For Juan Carlos Atienza, of the Spanish Society of Ornithology (SEO/BirdLife), “this is a joke that has no science.” “We are surprised that the University of Alcalá allows its name to be used for something like this, which evidently only tries to disguise wildlife,” says the ornithologist. “It is clear that this professor has a conflict of interest in this research.”

For his part, the University of Alcalá researcher at the center of the controversy maintains that his links to wildlife do not affect the independence of the study. “My personal hobbies are the same and my professional career is completely different, I think you have to know how to separate them,” says López.

Regarding the fact that his specialty at this public university in Madrid is the theory of signals and communications, a discipline that has nothing to do with biology, conservation or birds, the engineer replies: “I have been dealing with environmental issues related to the application of geographic information techniques in telecommunications for many years.” “Furthermore, I am the one who leads the team, but I am not the only one, forestry engineers, biologists, computer scientists work with me, let’s say I am the visible head, because someone has to be there”, he maintains.

Wilderness is a practice with a great tradition in some parts of Spain which still has thousands of enthusiasts today. Apart from the ethical debate on keeping birds in cages, today the capture of finches is prohibited by European laws, except for small quantities where justified. To get an idea of what this form of hunting entailed, from 2013 to 2018, the capture of 1.7 million finches was authorized in Spain, according to an estimate that appeared on Nature by researchers Jorge Gutiérrez, from the University of Lisbon, and José Masero, from the University of Extremadura. Despite the current ban, it is allowed to use specimens from captive breeding to cross them in search of the best songs or the best plumage colors. This alternative, however, does not satisfy hunters.

Professor López has in fact already delivered to the Government of Andalusia a first investigation dedicated to evaluating the feasibility of captive breeding on which he has been working for the last five years, with the support of the Community of Madrid. This study is not part of the part financed by the Andalusian Government, although it is part of the task of completing this evaluation with a comparison with other works on livestock farming.

Last September, the Andalusian Hunting Federation (FAC) formally presented to the Council a proposal “to recover wild catches in the natural environment” using research from this University of Madrid as scientific support. According to the text released by the FAC, “the scientific study prepared by Alcalá de Henares concludes that there is currently insufficient scientific knowledge for the development of captive breeding of finch species with which feralism is practiced”.

This alleged conclusion does not agree with the testimony of those wildlife experts who tell in Internet forums how they raise the birds themselves. Paradoxically, it is not possible to consult the content of López’s research at the moment, since the professor from the University of Alcalá refuses to show the work to EL PAÍS. “This study on captive breeding is in the hands of the Andalusian government, they are the ones who should think about making it public, I can’t say much more”, replies López. For its part, on behalf of the Regional Council, the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment specifies that “work is still being done on the document, when we have the conclusions we will report on it”.

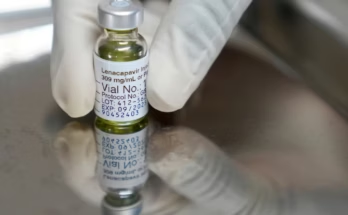

In the meantime, the part of the study financed by the Government of Andalusia has begun which evaluates finch populations and analyzes their migratory movements, through captures and ringing in Andalusia authorized by the regional administration expressly for the scientific work of the University of Alcalá. For hunters, demonstrating that these species are not endangered would be a further argument for claiming wild catches.

Having just begun, this field work in Andalusia is also causing great controversy due to the way in which the people who capture and ring the finch species have been trained (a very delicate operation), given that a completely unconventional route has been chosen.

There are three bodies in the country officially recognized for the training of ringers in the country, always following common criteria valid throughout Europe: Aranzadi (where the Doñana Biological Station and the Balearic Ornithological Group are integrated), the Catalan Institute of Ornithology and Seo/BirdLife. However, Professor López is opening the door for those participating in his studies both in Andalusia and Madrid to capture and ring specimens with a virtual course offered by the University of Alcalá itself.

The telecommunications engineer defends that nothing can stop him from also training banders: “Is it because a public university or any higher education institution is incapable of imparting knowledge, whatever it may be, if they have the appropriate qualifications and personnel?” However, ornithologists and scientists who regularly work with birds question whether these personnel are officially authorized to carry out this task and argue that there are common rules so that, regardless of where the specimens are ringed, the information can be used by everyone. According to Atienza, of Seo/BirdLife, “this project and this professor are outside the Spanish and European scientific grouping system, which makes their data useless for the scientific community and calls into question the results obtained.”