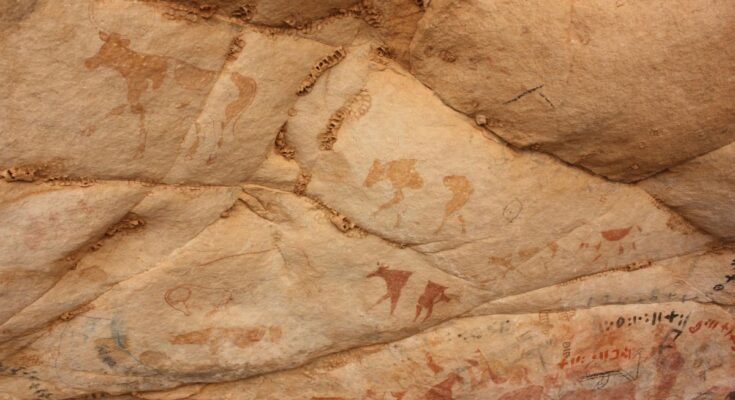

Have you ever wondered what music was like in the Stone Age? Some acoustic archaeologists examined the question after discovering that prehistoric cave art, created between 40,000 and 3,000 years ago, was meant to be seen, but also to be heard. “The oldest decorated sites convey a solemn and whimsical resonance; if you sing, the cave suddenly seems to respond to you“, explains Rupert Till from the University of Huddersfield in England.

Getting strong scientific evidence to support this idea is not easy. However, seven years of research into the acoustic properties of rock art sites around the world have now achieved this. New Scientist returns, in an article, on this progress.

The Artsoundscapes project is beyond doubt: prehistoric artists deliberately painted in places where echoes, resonances and sound transmissions created extraordinary sound effects. “I was really surprisedsaid Margarita Díaz-Andreu, archaeologist and project leader at the University of Barcelona, Spain, recalling her experience in the Valltorta canyon, in the eastern part of the country. Before the painting there was almost no echo, but as we approached, the sound immediately changed.»

By studying the specific soundscapes in which ancient works of art appear, Margarita Díaz-Andreu, Rupert Till, and other archaeoacoustics researchers began to see things more clearly. In doing so, they reconstruct the way these ancient, multisensory illustrations amplified the power of prehistoric rituals, stories, and shamanic musical performances – and, perhaps, altered the listener’s state of consciousness.

Reznikoff method

The first researcher to use song to enrich our understanding of Neolithic humans was a French musicologist named Iégor Reznikoff. He studied Paleolithic caves inhabited 18,000 to 11,000 years ago before publishing his findings in the late 1980s.

By counting the seconds between echoes, he noticed a correlation between the location of the cave paintings and the acoustic phenomenon. “Yegor can enter caves, make sounds, and guide you to cave art by listening for his echoesexplained Rupert Till. I’ve been to this cave with him before.»

Iégor Reznikoff’s method for “dialogue” with the wall was less than rigorous and his conclusions were largely ignored by archaeologists. But one of the first to investigate the findings more deeply was Steve Waller of the American Rock Art Research Association, who recorded echoes of up to 31 decibels in some decorated locations in deep caves in France, while the unpainted walls of the same caves were acoustically dead.

Although these discoveries helped advance the field of archaeoacoustics, many researchers continue to view it as a marginal discipline. That’s why, in 2018, Artsoundscapes was launched – a project that introduces cutting-edge methods for measuring sound phenomena at rock painting sites around the world.