The Spain of 2025 has little to do with the one that buried Franco in 1975. The arrival of democracy brought rights and freedoms and brought us to the European Union. It also coincided with the social and technological transformations that have changed our lives. In fifty years, Spain has become a larger, richer, healthier, more educated and more egalitarian country. Let’s analyze with 20 graphs what has changed since 1975.

A country of rights and freedoms. The first and main difference is evident: Spain has gone from being a dictatorship to a rule of law. Measuring a country’s level of freedom is complicated, but several academics from the V-Dem project have estimated an index for each country in recent decades. Spain’s progress in this index is extraordinary. It has gone from being on the level of some republics associated with the former Soviet Union to approaching, and even exceeding, that of other Western countries such as the United States or Germany.

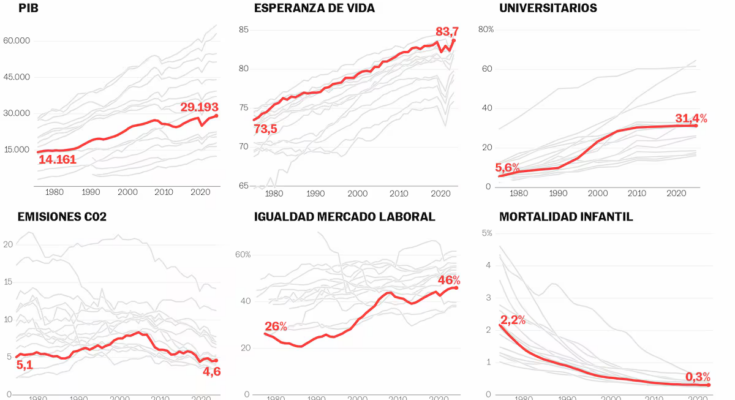

Spain is a country for the elderly. Another of the most significant advances of the last 50 years is that of life expectancy. For a child born in 1975, life expectancy was approximately 73.5 years. In 2023 it was 83.7 years old and, in 2024, it exceeded 84 years old for the first time, according to the latest data published by the National Institute of Statistics. This figure rises to 86.3 years in the case of women.

Spain already stood out among other surrounding countries in 1975, but the rise of these five decades has placed it among the longest-lived countries on the planet, behind only Japan, South Korea, Andorra and Switzerland.

This progressive increase in life expectancy, added to the decline in the birth rate, has transformed the demographic pyramid. In this half century the weight of those over sixty-five in the total population has doubled: they went from representing 10% in 1975 to now exceeding 20%.

Spain is a richer country today. In the 1980s and 1990s it experienced an exceptional economic leap with integration into Europe. By the turn of the century it had nearly doubled its 1975 GDP per capita, but growth has slowed since then. It collapsed during the crisis and the pandemic and now appears to be recovering at the pace of job growth.

Despite this economic growth, inequality has not been drastically reduced in recent decades. This can be seen in the Gini index, which has moved at the pace of periods of crisis and economic expansion, and which today is similar to that of 1980, around 0.32. This is also demonstrated by the data on the accumulation of wealth: in 1995 the richest 10% of the country accumulated 58.3% of the wealth; today 57.2%.

Spain is also a more educated country. In Spain, in 1975, almost one in three adults between the ages of 15 and 64 had no education. A percentage that was then well above other neighboring countries such as Germany (7%), Italy (5%) or France (1%). The universalization of education changed that story: in thirty years the percentage dropped to 0.5%.

Additionally, young people now spend more time in the classroom. In 1975 they studied for about 6 years; in 2020, more than 12. One key was the university’s expansion. Since the 1970s, the percentage of adults with a tertiary education has increased fivefold, from 6% to 31%.

This jump has been particularly strong among women. In 1975 they were only 30% of university students. Today they are the majority, 57%.

More women working. Another area in which the presence of women has increased is the job market. In 1977 only 26% of women had a job or were looking for one. Today it is at 46%. This is a huge leap: almost double in just three decades. Spain already surpasses countries such as Italy or Romania, although it is still behind the Nordic countries, where female participation is close to 60%.

And also legislate. There is still no equality in the Congress of Deputies, but over the last 50 years the progress of women in Parliament has been unstoppable. After the first democratic elections, in 1977, only 21 of the 350 seats in the lower house – 6% – were occupied by women; today they exceed 44%. Although this equality also exists in the Government, in fifty years of democracy Spain has not yet had a female Prime Minister.

A country with 12 million more inhabitants. Spain has grown from 36 million inhabitants in 1975 to more than 48 million, according to the latest INE census. It grew steadily until the 2000s, when it took off with the arrival of the migrant population. Although population growth has been a global phenomenon, in Spain this increase has been particularly notable. Over these five decades, the population grew by 34%, slightly above neighboring countries, such as the Netherlands, Sweden or France, and below the United States or South Korea.

A Spain that grows and another that empties. Much of this population increase has been absorbed by the cities. 50 years ago, 70% of the Spanish population lived in urban areas; Now this percentage has risen to 82%.

This has led to uneven growth in the area. On the map – which shows how the population has changed in each province – notable increases are observed in the center and on the Mediterranean coast, where provinces such as the Balearic Islands, Alicante, Almería or Guadalajara have doubled their population. In the interior, several provinces of Castilla y León or Galicia now have fewer inhabitants than in 1975, in particular Zamora (which lost 33% of its population), Ourense (30%), Lugo (21%) and Ávila (19%).

Spain today emits less CO₂ per capita. In 1975, per capita emissions were around 5.1 tonnes and grew for decades to exceed 8 tonnes in the mid-2000s, coinciding with the economic boom. Since then the trend has reversed: today emissions have fallen to around 4.6 tonnes per capita, almost half compared to twenty years ago. They are three times lower than those of the United States and are well below those of South Korea, Japan or Germany, although still slightly higher than those of France or Portugal.

One of the main reasons for this reduction over the last two decades is the expansion of renewable energy. In Spain, today 57% of electricity is generated from renewable sources, more than double compared to 1985.

Fewer children, but healthier. In 1975 there were 2.5 births per woman, a figure which has significantly reduced. In 2023, the latest year with data, the rate was 1.2 births per woman. Spain has gone from being one of the countries with the highest fertility to being among those with the lowest fertility. Furthermore, these births occur later: the average age of mothers at the birth of their first child has increased from 28.8 to 32.5 years.

The good news is that infant mortality has plummeted. The percentage of children dying before reaching the age of five fell from 2.2% to 0.3%, much lower than in countries such as Romania or the United States.

From a country of emigrants to one of immigrants. Starting after the war and especially in the 1960s and 1970s, thousands of Spaniards emigrated to other European countries, some fleeing the repression of the regime and others in search of better work in countries where the economic situation was better than that of Spain, such as Germany, France or Switzerland. After the dictator’s death, and encouraged by the economic growth of the 1980s, many of these emigrants returned to Spain.

In recent decades, Spain has become a country that welcomes migrants and today they already represent 20% of the population. Its presence is particularly relevant in provinces such as Alicante (30%), Balearic Islands (29%) or Girona (28%).

Less agriculture and industry and more services. The profile of jobs has also changed. The industrial reconversion of the 1980s, the integration into the European market and the expansion of tourism and services have intensified the delocalisation process. In 1975 this sector employed around 40% of workers; Today it occupies 75% of it, a figure close to other neighboring countries such as France or Germany. On the contrary, the sum of those employed in agriculture and industry increased from 48% to 18%.

Four times more doctors and three times more teachers. The increase in life expectancy in these five decades responds to several causes: the improvement of habits, medical and pharmacological advances, socioeconomic progress and, above all, the expansion and consolidation of a universal healthcare system. This universalization was accompanied by a notable growth in healthcare personnel: in half a century the number of doctors and nurses per 1,000 inhabitants tripled, going from 3.4 to 13.7.

The universalization of education has also increased the number of teachers. In 1975, according to the Ministry of Education yearbook, Spain had around 300,000 teachers at non-university level, 40% of them in private or subsidized centres. Today the panorama is different: there are 800 thousand teachers and 75% work in public centres.

The growth of college campuses has been even more spectacular. Five decades ago there were approximately 27,000 university professors (22,000 of them men). Today there are more than 140,000, five times more. Added to this figure are another 33,000 researchers and research support technicians.