Spain celebrated half a century of parliamentary monarchy on Saturday. It was the political form agreed to move from a long-term dictatorship to a democratic system comparable to that of other Western countries. And Juan Carlos I – chosen as successor by Francisco Franco – was its greatest representative for 39 years. A period in which Spain approved an advanced Constitution, entered international organizations such as the European Community and NATO, hosted Expo ’92 and the Olympic Games, took off on the back of economic growth and managed to escape international ostracism. But also a time of scandals on the part of Juan Carlos de Borbón, who, in his recent memoirs (ReconciliationStock) recognizes some “errors”. The book, already published in France, will be published in Spain at the beginning of December.

As part of the anniversary, four of the five living heads of the King’s House – Jaime Alfonsín, who held the position between 2014 and 2024, refused several times to participate – share with EL PAÍS their experience as first swords who, in the shadows, learned in depth the details of the head of state and the contradictions of Juan Carlos I. The four also reflect on the challenges of the present and future of the institution embodied by Felipe VI and Princess Leonor.

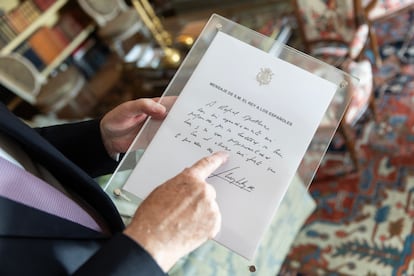

The first years were a historic stage, agrees Fernando Almansa (head of the Chamber from 1993 to 2002); Alberto Aza (2002-2011); Rafael Spottorno (2011-2014) and Camilo Villarino (since 2024), all diplomats and civilians, after two generals (Nicolás Cotoner y Cotoner and Sabino Fernández Campo) held the position for 18 years. “At the time, the big debate was whether regime change should happen with a break (with the Franco regime) or with a reform. And Juan Carlos I was the person who piloted that reform,” says Almansa from the living room of his home, full of memories of his time as the Monarch’s right-hand man. His successor, Alberto Aza, underlines from a sober office at the Council of State that the monarchy was the “political solution to a long period of crisis” and adds that the “parliamentary” surname is fundamental because it is the formula that allows all power to be in the executive and that the king has a symbolic and representative role, which, according to the four, offers the most precious quality of this system compared to a republic: neutrality.

Aza recalls how he himself was, however, “skeptical” about that process of opening towards the Transition until he met Adolfo Suárez, muñitor together with Juan Carlos I and Torcuato Fernández Miranda, among others, of the political reform that led to the 1978 Constitution. “It seemed to me that someone had seen the light at the end of the tunnel”, he summarizes. Villarino adds: “(the king emeritus) has turned the regime inside out.”

Spottorno recognizes that he was much more pessimistic in the moments when the foundations of a new country were beginning to be laid, and remembers how he braked abruptly when he heard on the radio that Juan Carlos I had appointed Suárez, then general secretary of the Movement, president of the government. “I put my hands on my head and said: ‘This man is crazy, what nonsense. Liquidated’. However the move came out: taking risks is in his character,” he warns of the king emeritus.

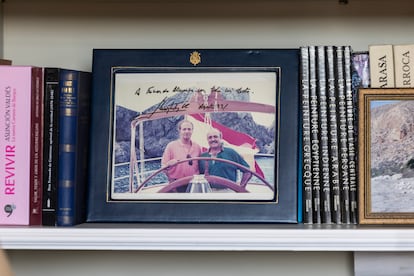

The personality of Juan Carlos I marked his reign. Those who worked with him highlight his “open, liberal, disciplined and orderly character” – “he is a soldier,” they point out – as well as “his punctuality, empathy, pragmatism and instinct”. “He was a very nice character, there’s no doubt about it. And that’s an advantage,” says Aza, who reveals that in Morocco – the king emeritus maintained excellent relations with Hassan II, as well as with Hussein I of Jordan – Don Juan Carlos was said to have “baraka” (good luck in Arabic). The person overcame the institution and soon people began to talk about Juancarlismo, something that Aza, who lived through the last moments of that golden age, criticizes: “The fact that they talked about Juancarlismo was a weakness in recognizing the institution, overestimating the person.”

Spottorno believes that this “volcanic” and “stormy” personality of Juan Carlos I led him to contradictions throughout his reign. He recalls how in 2011, after a period marked by very high popularity and “overwhelming” international activity, the king was “tired”. It coincides with the years of scandals, finally discovered: multi-million dollar donations from the Gulf monarchies; infidelity… The former fifth head of the House attributes this boredom to the fact that almost four decades of reign in a “complicated” country can produce “dismay”. Only 50 years ago Spain maintained diplomatic relations with 85 states; in 2014, with 191. The promotion of the Kingdom – in the first years priority was given to the relationship with the United States, Europe, Latin America and North Africa – “no longer required so much activity from the King”, he adds. He was “more back to everything”, which led him to focus on personal matters that “were not always fortunate and to neglect public issues a bit”, recognizes one of the men who piloted the abdication.

But of all that could have happened then, when the institution’s reputation was in tatters due to, among other episodes, elephant hunting in Botswana when the Spanish risk premium was skyrocketing, “the least worst,” they agree, “was what happened”: the abdication. “Those of us who were there to take care of him,” Spottorno laments, “did not know or could not do so as would have been desirable so that (Juan Carlos I) could maintain the same prestige he had in the past.” It refers to the time when it was said that the King was the best ambassador of Spain and when nothing or almost nothing foreshadowed the earthquakes to come: the Noós casewith an infant in the dock and a son-in-law in prison; the great recession; judicial investigations inside and outside Spain, accounts and foundations abroad, two tax regularizations and a move breast die in Abu Dhabi.

For Almansa, these are “anecdotes”. “Kings,” he adds, “are remembered for their political legacy.” Juan Carlos I, Spottorno believes, “did things he shouldn’t have done, but he did many others. He built a country almost from nothing”.

Two very different kingdoms

When Philip VI – the first king to swear on the Constitution, as Princess Leonor also did when she turned 18 in 2023 – took over from her father, the situations of the two kingdoms were already “very different, both nationally and internationally”, says Villarino, the current head of the King’s House, from his office in La Zarzuela.

“This is a more difficult Spain from a political point of view,” underlines Almansa, who lists the challenges: a more fragmented Parliament, more tensions, the end of the two-party system, more radical independence movements… “All this makes his role more difficult for the referee (now Felipe VI) than it might have been for his father.”

“This is a more difficult Spain from a political point of view,” underlines Almansa, who lists the challenges: a more fragmented Parliament, more tensions, the end of the two-party system, more radical independence movements… “All this makes his role more difficult for the referee (now Felipe VI) than it might have been for his father.”

It is in this complex context in which there is great “tension, polarization and exacerbation of factionalism”, adds Spottorno, that an arbitrator who wants to represent all Spaniards becomes “indispensable”. “The power of moderator can be very useful in certain moments, well exercised and with a desire for unity and détente between opposing political forces. It is something very positive”, he continues. For Almansa the role of referee “makes the institution even more important today”. Villarino, the latest arrival at Zarzuela, points in the same direction: “If a monarchy can surpass a republic in anything, it is political neutrality”, he says against those who delegitimize the institution precisely because Juan Carlos I was designated exclusively by Franco as his successor.

The appointment by the dictator was a “handicap”, Spottorno acknowledges, but the transformation he brought to the country was “almost a miracle, a sort of revolution”. “The problem,” adds Aza, “was not whether he would become his (the dictator’s) successor, but how he would do it. Whether he would continue with Franco’s rule or exactly the opposite.”

Villarino, who now has to deal with a much smaller Chamber than that of his predecessors – the infantes Elena and Cristina are no longer part of it and the king emeritus, despite being under his responsibility, does not have an official agenda – believes that what differentiates the monarchy of Philip VI from that of his father is that he is now faced with “unprecedented” situations, such as the activation of article 155 of the Constitution after the unilateral declaration of independence of Catalonia or the importance that rounds of consultations of the candidates for the presidency of the Executive.

As for the future of the monarchy, now that the milestone of the fiftieth anniversary has been reached – a celebration to which Juan Carlos I was not invited – the four former heads of the Chamber agree that the Royal Family must demonstrate its usefulness and exemplary attitude every day. “The only thing that can harm the monarchy is if it becomes irrelevant,” Spottorno believes.

Those who know him well underline Philip VI’s ability to listen and his kindness. “He is attentive, curious and eager to learn,” says Villarino, aware of republican sentiments and the mark that the behavior of other members of the Royal Family has left on society. For this reason he repeats to Philip VI that he is the King “of all”. His red line, he concludes, is that no one can be ashamed of his boss: “May no one be able to say: ‘I’m ashamed’”.