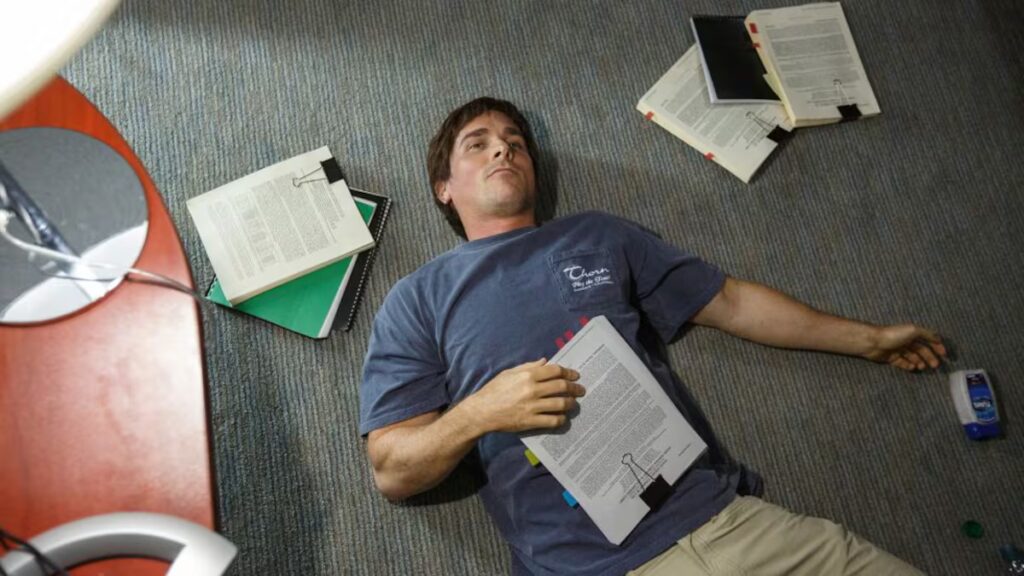

Michael Burry was the investor who identified the fragility of the American mortgage market before anyone else and decided to bet against it before the 2008 crisis. Christian Bale played Burry in the film The big bet. He realized that mortgages subprime It was nonsense that piled up hidden defaults, a house of cards legitimized by institutions like Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers and JP Morgan. Now he feels the same way about the artificial intelligence sector, which is why he has abandoned his stake in Nvidia, the most solid company in the sector. His logic is based on the hyperinflation of the immediate value of AI and a small accounting detail.

Everyone goes into debt to build the physical infrastructure of artificial intelligence: servers, data centers, fiber optics, machinery and, above all, Nvidia chips at crazy prices. As a result, Nvidia is the only one that has the chips and the only one that has cash flow. In the midst of this bonanza, Nvidia has started investing in companies like OpenAI so that they have enough money to continue expanding data centers and filling them with Nvidia H100s. We called it, ironically, “circular economy”. Technically, the expansion increases OpenAI’s value, making Nvidia’s investment worth more. But Nvidia counted that money as a profit and not an expense; and also OpenAI.

When companies borrow to build infrastructure, the spending is recorded not as an expense but as an asset that depreciates over several years. One of Burry’s arguments is that Nvidia chips expire in just three years, and that OpenAI would have to earn incredible amounts of money to pay for them. An unlikely challenge, given that it is losing three times as much money as it makes and is on track to post a net loss of $27 billion before 2026. Nvidia also doesn’t record its investment in OpenAI as an expense but as a financial asset, and counts the chips as a sale, even if it hasn’t cashed in on them yet. That’s why it can indirectly finance OpenAI’s growth with graphics processors and cash without reducing the quarter’s operating profit. But if the market loses patience and the bubble collapses, Nvidia will not sell its units and will also lose its investment.

The latest report from consultancy Bain estimates that to meet the expected demand for artificial intelligence by 2030, “hyperscalers” would need to generate around $2 trillion in new annual revenue, more than global military spending. An estimated $800 billion shortfall for an infrastructure that requires the total energy of 200 large nuclear reactors. Artificial intelligence does not adapt to the world, especially if it has to share it. Something similar happened with the dotcom bubble.

The Internet has outlived its promise, but in the 1990s many went into debt to build the infrastructure before a market existed for its exploitation. Large, recently privatized infrastructure providers such as Telefónica, France Télécom or Deutsche Telekom have survived. New companies that laid fiber optics in the ground failed, and the same thing happened with precursors like eToys or Pets.com, leaving mountains of servers on credit. From those ashes, platform capitalism was born. The question is: can we think of something interesting to do with the ashes of this bubble or will we let them be eaten by Amazon, Google and Microsoft.