Núria Quevedo died as she lived: forgotten by her country, Spain, and slowly devoured by that concept of distance which she herself invented to describe the strange closeness of what is far away, which is what becomes the homeland for those who are torn from it. The painter from Spanish exile, deserving of a place of honor in 20th century political art if only for the strength of one of her paintings, died this Saturday, at the age of 87, in Berlin.

He had lived there since he was 14, when he arrived in exile in the German Democratic Republic like many other anti-Franco Spaniards in the 1950s. His family: his father was an aviator in the Republican Army; His mother crossed La Jonquera on foot in 1939 after the end of the war – she joined the ranks of those republicans, communists and anarchists who, to survive the defeats that history was inflicting on them, fell into the nostalgic clutches of exile. And that’s what Núria Quevedo painted: the tear for the lost land. The heavy emotional burden that doesn’t fit in any suitcase.

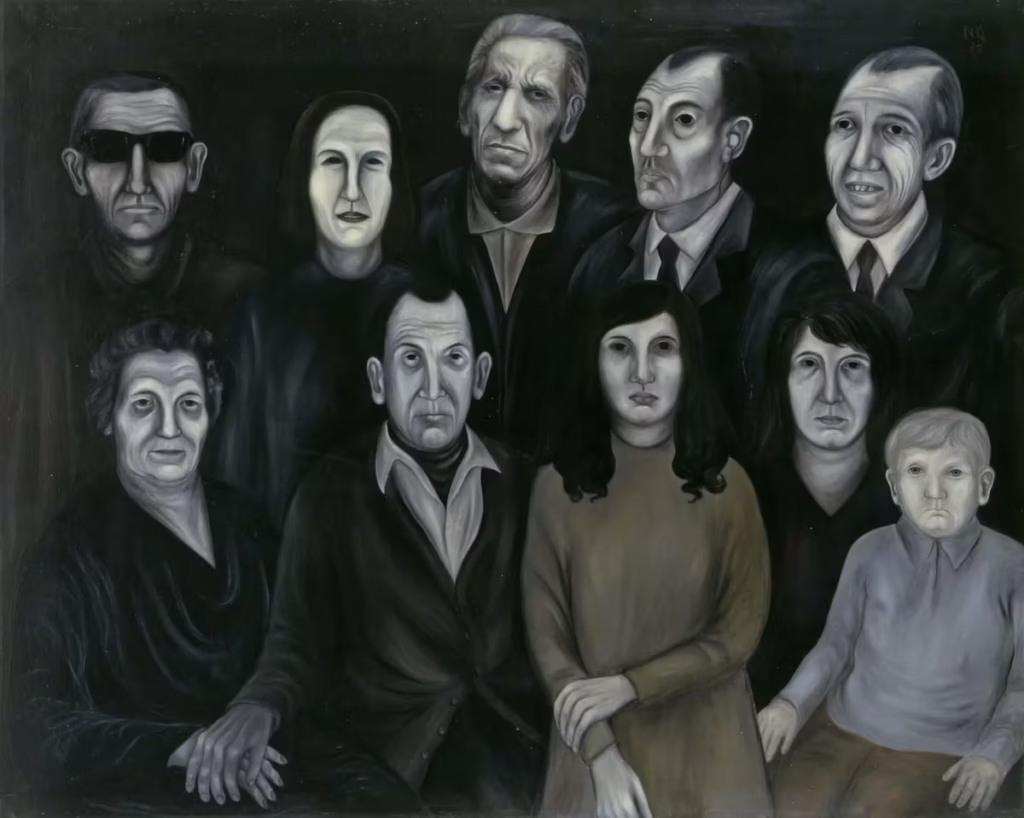

It’s called the painting that never gave him the recognition he deserved Thirty years of exile (1971). From this impressive oil painting emerge ten hypnotic faces that peer at the viewer and delve with curiosity inside. Those ten tired and suffering faces, belonging to the Spanish diaspora in the GDR, are faces of a baroque darkness and an expressionism that wounds in its sincerity. The ten inhabitants of this “Gernika of exile” look like ghosts. They are silent, very still, terribly serious; as if pierced by that chained disappointment which was the defeat of the Civil War, the long establishment of Franco’s dictatorship in Spain and the impossibility of democratic communism in Germany after the Soviet tanks in Prague in ’68.

The ten characters in the enormous painting – 120 x 150 centimeters – are a vivid image of uprooting. Of melancholy for all that is lost. Of nostalgia for what never happened. Of the harshness felt in the host cities. Del distance of the homeland, seemed like a sting in the cold and cloudy afternoons of the GDR. This is why Núria Quevedo painted so many rainy landscapes, so many solitary, meditative and isolated human figures in the city of short days and long winters: because she never forgot the girl who arrived in Berlin in 1952 with braids and white socks. Because he always had in mind that youth who faced the helplessness of exile in the long and lonely hours spent in the bookshop that his family ran in East Berlin, listening to the slow and sad bells that tolled at six in the afternoon in a nearby church.

That melancholy, filtered by contemplative reflection, introspection, helplessness and disappointment in the face of the lost dreams of this PCE member devoted to Don Quixote, was the driving force of a work that did not stop growing during Quevedo’s more than sixty years of active work in painting, drawing, engraving and book illustration. An artist coming from Spanish exile with more than enough credentials to be included in the orbit of Maruja Mallo, Remedios Varo, Roser Bru, Marta Palau, Manuela Ballester, Mary Martín or Victorina Durán. But this never happened. Oblivion was his double phrase.

Although in Spain – even in her native Barcelona – she was ignored by the cultural elites, with the honorable exception of the writer Erich Hackl, in Germany she achieved recognition. In the seventies he received a scholarship from the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin. In the 1980s he was awarded the Goethe Prize by the Municipality of East Berlin. Some of his works, recognizable by the characters with large hands and round heads in profile, can be found in the most important art collections of the former GDR. Only three years ago the Brandenburg State Museum of Modern Art dedicated a large retrospective to him. And, shortly after, the Catalan artist, known by his nickname Die Berlinerin from Barcelona (“The Berliner from Barcelona”), received the prestigious Karl Schmidt-Rottluff Art Prize from Chemnitz for having reflected “in an impressive and overwhelming way” the uprooting caused by the loss of the homeland and the loneliness in a new society.

For four years I had corresponded with her regularly. Sometimes she spoke of the wild flowering of the yellow broom and the colorful splendor of the lilacs in the Berlin garden of her home, shared with her life partner, the director Karlheinz Mund. Other times he lashed out with ideological barbs: “Hope is often insidious: so much hardship, so much death, so much suffering.” He has always celebrated gifts: a book on the Republic, a protest song and a love song by Raimon, a melancholic tango by Gardel, a phrase by Walter Benjamin and his angel of history. This was the canvas of his life: his face turned to the past and its piled up ruins.

Can you be friends with someone older than fifty who you’ve never met? This must also be the distance. Can you still feel close to a dead friend? That too will be distance.