One of the greatest symbols of Franco’s fanaticism remains unscathed at number 125 Via Serrano in Madrid. Here stood the Auditorium of the Council for the Expansion of Scientific Studies and Research (JAE), a temple of culture through which figures such as the physicist Marie Curie and the poet Federico García Lorca passed. After winning the Civil War in 1939, dictator Francisco Franco decided to dissolve the JAE and founded on its ashes the Superior Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), with a mission: “We must impose on the order of culture the essential ideas that inspired our Glorious Movement.” The Church of the Holy Spirit was built above the auditorium, donated to Opus Dei. A new investigation now reveals the extent of the repression unleashed against the republican scientific institution: the dictatorship carried out purge processes against at least 498 people administratively linked to the JAE, such as Carmen Herrero Ayllón, chemist and Spanish javelin throwing champion in 1930.

Historian Ana Romero de Pablos, co-author of the study, explains that the CSIC – Spain’s largest scientific organization – was “waiting” to carry out this exhaustive review of its history. In recent decades, steps have also been taken in the opposite direction. On February 25, 2000, the then president of the CSIC, the microbiologist César Nombela, who defined himself as “a Christian scientist” and was an inflexible anti-abortionist, signed an agreement with the Archbishopric of Madrid to grant free use for another 69 years of the Church of the Holy Spirit, a building which is currently owned by the scientific institution.

The current president of the CSIC, Eloísa del Pino, has promoted since her appointment in 2022 a cleansing of all Francoist traces, to respect the Law on Democratic Memory. He says that after taking office, he walked every day through corridors filled with tributes to dictatorship figures. In April 2023, he ordered the removal of the portrait of the first CSIC president, José Ibáñez Martín, for participating in “repressive actions” during the nearly three decades of his mandate. “We want a Catholic science,” Ibáñez Martín himself proclaimed in 1940 before the dictator. “We therefore ask God, sovereign possessor of essential, independent, intuitive, one, infinite and infallible science, to send his Holy Spirit upon Spain (…) and to give us the gift of true and eternal science,” said the CSIC president, who was also Franco’s minister of national education.

The new investigation, called Science, Purification and Memory, delved into the archives to try to put a face to all those purged by the JAE. To everyone, even “janitors and cleaning women”, as Ana Romero de Pablos underlined on November 3rd in a round table organized at the University of Madrid. “In the CSIC there are still many traces of its Francoist origins, which decades of democracy have not managed to erase. On the other hand, we know that during the Francoist era many of the documents that contained and made visible the work and people who participated in the JAE were erased”, declared Romero de Pablos, of the CSIC Institute of Philosophy.

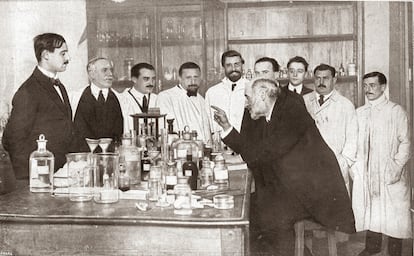

The Committee for the Expansion of Scientific Studies and Research was created in 1907, amidst the national enthusiasm following the Nobel Prize for Medicine won a year earlier by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, cartographer of the human brain. The new institution, created “to closely follow the scientific and pedagogical movement of the most cultured nations”, dedicated itself for three decades, with Cajal himself as president for life, to paying for the stays of Spanish scientists abroad. Furthermore, within it grew the entities responsible for the so-called silver age, such as the Cajal Institute and the Student Residence, which contained the imposing Auditorium converted in 1942 into the church of Opus Dei.

Historians Ana Romero de Pablos, Irene Mendoza and María Jesús Santesmases have been digging in the archives for two years and, at the request of EL PAÍS, present four cases of retaliation. The doctor Juan Miguel Herrera Bollo was 27 years old when he entered as an assistant at the Cajal Institute in Madrid in 1933. During the Civil War, he enlisted in the People’s Army of the Republic as a doctor stationed in a military hospital in Madrid. “Franco’s purge sanctioned his definitive separation from his work,” recalls Romero de Pablos. The doctor, imprisoned in the provincial prison of Madrid, was sentenced to death for alleged blood crimes, but was finally acquitted in 1944. Unjustly identified as a criminal, he took the path of exile and settled in a neurosurgery institute in Panama. The new authorities expelled more than 40 percent of scientists linked to the JAE, according to an earlier study by historians Antonio Francisco Canales and Amparo Gómez.

Purges and revenge

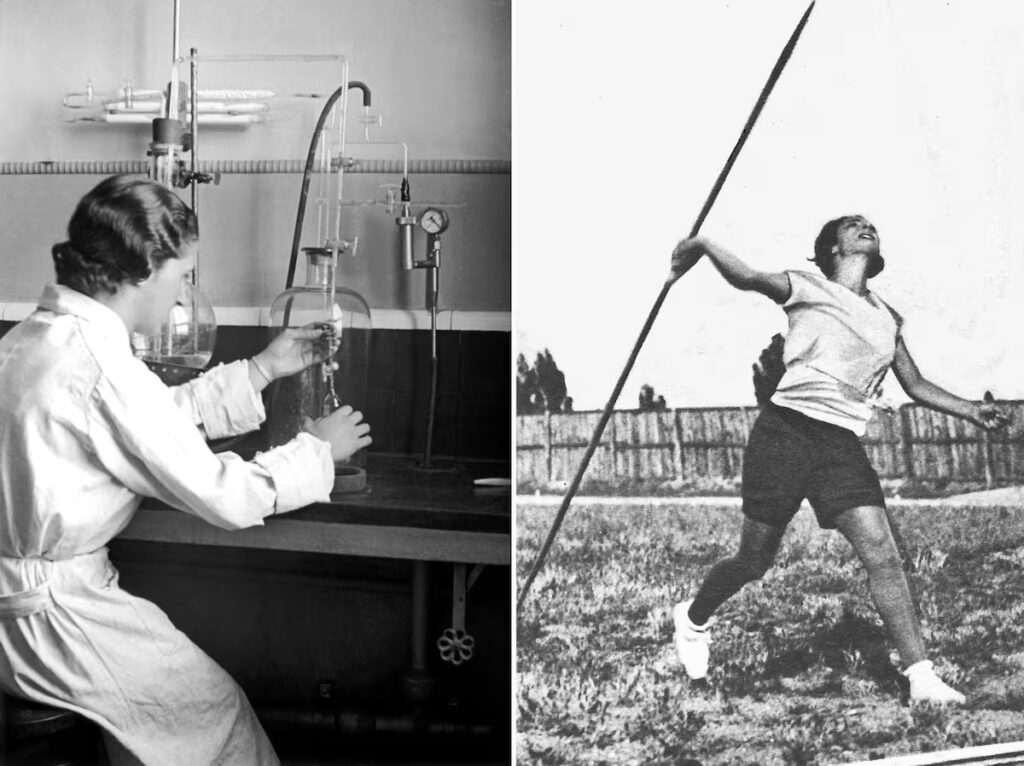

Romero de Pablos underlines that “the purification system was characterized by a very high degree of arbitrariness”, with sanctions often marked by simple personal revenge. “The Franco regime sought to eliminate from public life anyone who identified with the Republic, liberalism, secularism, socialism or any form of thought that questioned national Catholicism,” says the historian. “It was a justice designed not to discern real guilt, but to impose an exclusive political and moral order,” he adds. After the Civil War, people who had done absolutely nothing wrong were involved in the fearsome purification processes, such as Carmen Herrero Ayllón, a pioneer of chemistry and women’s sports in Spain.

Herrero Ayllón, a 1933 graduate of Madrid, went to work at the National Institute of Physics and Chemistry of the JAE. As a student, she set the Spanish women’s javelin throw record, with a distance of 26 and a half metres. After Franco’s victory, he underwent a Kafkaesque purification process that ended without sanctions in May 1940. His life would never be the same again, according to Irene Mendoza, also a historian at the CSIC Institute of Philosophy. “Although Carmen Herrero Ayllón was able to return, her professional career ended up being oriented towards teaching rather than research, which also happened in other cases of women of the time,” she points out.

That National Institute of Physics and Chemistry was renamed the Rocasolano Institute, in homage to Antonio de Gregorio Rocasolano, the director of the National Commission for the Purification of University Personnel. The name of the repressor remained until April 28, 2023, when the president of the CSIC ordered it to be renamed the Blas Cabrera Chemical-Physical Institute, in honor of the Canarian physicist, an international eminence in the field of magnetism, who was also purged by Francoism and died in exile in Mexico.

Historians recall cases of internal exile, such as that of José Miguel Sacristán, a psychiatrist who participated in the analyzes of Hildegart Rodríguez, the famous child prodigy murdered by her own mother in 1933, at the age of 18. The researcher had directed the Physiological Chemistry Laboratory of the JAE and the women’s mental hospital in Ciempozuelos, but during the Civil War he had to work as a doctor in a Republican military hospital. After Franco’s victory, a first purge process prevented him from returning to work and a second file banned him from practicing medicine, accused, among other things, of having signed the manifesto of the socialist Juan Negrín, a physiologist trained at the JAE and president of the Council of Ministers of the Republic until the end of the Civil War. Expelled from public life, Sacristán had to earn a living as a translator and practicing medicine in his private practice, historians recall.

“The purge became an essential tool for the configuration of the new State. It was not an isolated or exceptional act, but a policy that continued over time”, underlines Romero de Pablos. “Franco’s purge, which began in 1936, structured and conditioned Spanish public, educational and scientific life in some cases until the 1970s,” he explains. In some cases, such as that of the Oviedo jurist Ramón Prieto Bances, the punishment was forced transfer. A professor at the University of Oviedo and a pious Catholic, he had briefly been secretary of the JAE and minister of public education. He had to move to Santiago de Compostela.

Historian Leoncio López-Ocón mentions the damn memoriaethe condemnation decreed by the Senate of ancient Rome which required the cancellation of all traces of an enemy: monuments, inscriptions, even the use of his name. “It is not very accurate to say that the CSIC is the heir of the JAE. The CSIC carried out a deliberate damn memoriae on the JAE,” he said during the meeting at the Ateneo López-Ocón, of the CSIC History Institute.

The researcher recalls that, after the Civil War, the first director of the Cajal Institute was the doctor Enrique Suñer, author of the pamphlet Intellectuals and the Spanish tragedy (1938). In its pages he defines the JAE as an “evil company” made up of “enemies of the Fatherland, of Religion”. Suñer urged us to “eliminate from our homeland those guilty” of “an infernal and antipatriotic work which, precisely because it was such, sought to eradicate the faith of Christ from the Spanish soul”. The architect of Opus Dei who transformed the auditorium into the Church of the Holy Spirit, Miguel Fisac, wrote in the project report: “If the primitive Christian churches arose from Roman basilicas, because from a theater or a cinema, where they were thought to dirty and poison, with diseases of culture and art, the Spanish youth, an oratory, a small church, cannot arise so that the Holy Spirit is the true guide of this new youth of Spain.”