from Rome

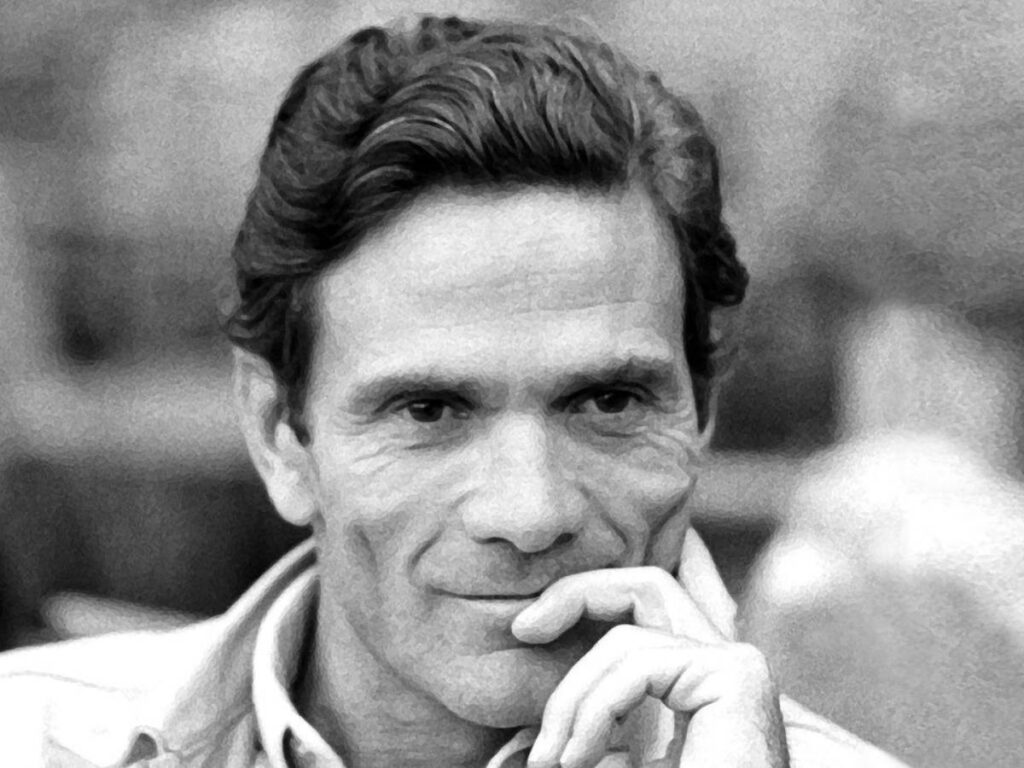

On the occasion of an exhibition dedicated to Leonardo Sciascia, a few years ago, a display case was displayed in Racalmuto containing a deadly exchange, an issue of Corriere della Sera, between the Sicilian writer and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Not one of the easiest topics: abortion. One is struck by the honesty of his words and the obvious respect between the two competitors. Those who eagerly welcomed Pasolini’s conservative conference, simply fixating on the title without then coming to listen, missed at least one lesson from Pasolini. Pasolini discussed it with everyone, from students, of any political orientation, to Leonardo Sciascia. Ah but yesterday Ignazio La Russa was there, that was cultural appropriation by the right. Well, God forbid the guest, the Senate President, doesn’t offer an institutional greeting before the conference (not after, and that makes a big difference).

Mind you sailors, saying “the right thing” doesn’t make you sound smarter. “Cultural appropriation” then constitutes an awakened animalism that undermines scholarship on Pasolini and debate over his works. Although Camillo Langone uses this phrase with gleeful sarcasm: “I have no problem taking Pasolini’s work”. A few days ago, in the DPR, right-wing groups were reminded of Pasolini, but the protesters there were fast asleep and didn’t even realize it. In that room, the leftists, who were very cultured, lined up five or six representatives. In short, an exchange, despite its heavy content but its respectful tone, is beyond the capabilities of intellectuals who feel that they are the keepers of the truth, and think to assert it by selecting here and there Pasolini phrases that suit their theses, often a superficial and confusing thing even if disguised by super cazzolese academicism. There was no appropriation, no entry of Pasolini into the ranks of the “right”. The controversy proved sickening and even insane. The excellent publicity considering too many reservations caused organizers to move to the much larger (three times the size) Senate chamber.

In reality, the right wing’s interest in Pasolini was the same as Pasolini’s interest in the right wing. Divine right. Pasolini in the early 1960s was a man of profound evolution, and his reading now goes far beyond the Marxist realm (without denying it, let’s be clear). Just one example. The film Medea stages a clash between Medea, a representative of the ancient world, immersed in purity; and Jason, the rational, spiritually insensitive defender of the modern world. Some scenes are remarkably faithful transpositions of a Treatise on the history of religion by Mircea Eliade, a former Romanian iron guard in quiet French exile.

Pasolini sided with sacred things because sacred things would soon be discarded in the name of the materialist efficiency of capitalism. The sacred is an instrument of resistance to power: it makes man divine and therefore untouchable. Take away the sacred, and society will begin to move on an inclined plane, where at its base there is a vicious human factory, absolute power over our minds, which tend to homologation, and over our bodies, which are ready to be polluted by technology. In reality, Pasolini’s work (more than twenty thousand pages) speaks to us of course about the past, but also and above all about our times.

All these aspects, and others, were touched upon by those present at the meeting organized by the Alleanza Nazionale Foundation in collaboration with Il Secolo d’Italia. The day opened with remarks from Ignazio La Russa, president of the Senate, Federico Mollicone, president of the Cultural Commission, Francesco Giubilei, director of the Scientific Committee of the Alleanza Nazionale Foundation, and Antonio Giordano, deputy and vice-president of the same Foundation. This was followed, in addition to the author, by the interventions of Alessandro Amorese, deputy and publisher, Paolo Armellini, professor at the Sapienza University of Rome, Gabriella Buontempo, president of the Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Andrea Di Consoli, writer, Camillo Langone, writer and journalist. Moderated by Annalisa Terranova, journalist, also author of an interesting speech about the relationship between Pasolini and MSI.

An anecdote to end with. Pasolini loved an unfairly forgotten writer (who sadly no one wants to appropriate, I’ll think about it). His name was Antonio Delfini, a brilliant outsider, completely unusual, because he didn’t care whether he was there or not.

He wrote a semi-serious (more serious) political manifesto. It was called the Manifesto for the Conservative and Communist Parties. He argued that development was not progress, and that only conservatives could become true communists.