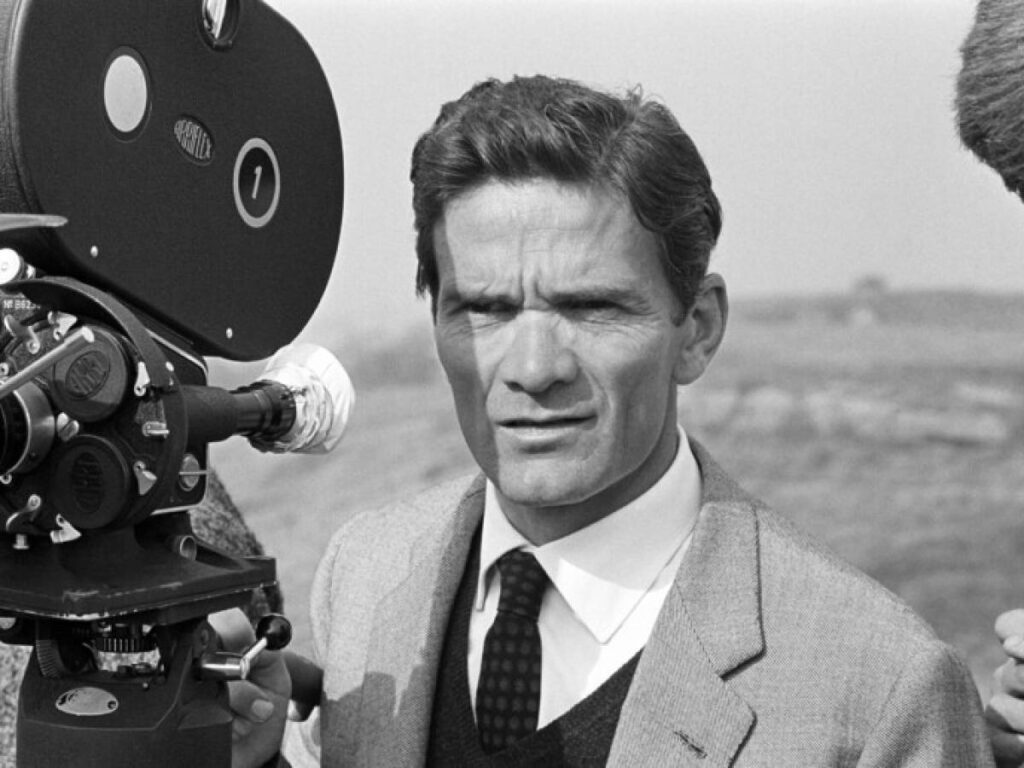

Every year Luiss holds a meeting where an Italian literary writer is read through a political lens. This happened to Dante Alighieri, Francesco Guicciardini, Eugenio Montale and Alessandro Manzoni. Two anniversaries in the near future – in 2022 is the centenary of his birth; in 2025 the fiftieth anniversary of his death – they chose Pier Paolo Pasolini. When the event was held, the controversy that tore apart the official organizers of the Pasolini celebration had not yet flared up. But those who took part already understand how slippery comparisons with Pasolini can be.

Pasolini is actually a modern contemporary for us. Its versatility influenced the relationship between culture, society and politics with such force that its reverberations continue to this day. It is difficult to decipher the process of secularization that transformed our country from a post-war rural reality to a modern industrial powerhouse to a post-modern outcome, without finding it. Most importantly, it is difficult if one does not want to avoid the contradictions – and sometimes paradoxes – inherent in this process. Let’s go back to 1974. This was a year in which divorce was rampant, the strength of the Christian Democrats weakened and, moreover, their ties with the Church. This was the year in which Pasolini wrote “empty of Charity, empty of Culture”, outlining the study of the anthropological revolution, celebrating the enormity of the peasant world in the face of historical limitations. A few months later, the most famous article about the disappearance of fireflies would follow. This was also the year in which Leonardo Sciascia published Todo Modo, in which the prophecy about the end of the Catholic party through explosion stems from the differences between secularism and secularism. Pasolini apparently responded with a series of more sombre articles, direct and uncompromising, aimed at the “palace court”. And in hindsight, this phase that then began seems almost to emerge, taking shape and ultimately leading to the tragic outcome, of the long-distance dialogue.

In fact, Pasolini’s politics were genetically contradictory. For reasons that range from the existential to the political. He had lost a partisan brother in Porzus, killed by another partisan on the orders of the PCI from Udine. However, he wanted to become a communist. He stubbornly wanted it even when he was expelled from the party. In Rome, where he retired, he experienced the full range of intellectual positions. And at the same time, suburban areas are the most degraded areas. In doing so, he acquired a unique, outrageous and heretical point of view. And the contradictions were so protracted, powerful, and violent that even fifty years later, they still have a disturbing double impact. Everyone nowadays can make their own Pasolini, forgetting the rest. And each person, moreover, even has the possibility of celebrating his perverted nature, to the point of turning the contradiction into a commonplace thing. Even a visit to the monument dedicated to him at the Ostia seaplane base, where he died fifty years ago, carries conventional risks. Which can be redeemed only if, towards the mouth, where the River Tiber becomes especially beautiful and unpredictable, you come to a place that passes under the Mezzocamino Bridge. Along a road that, for years without an anniversary, was littered with abandoned mattresses. Remains that communicate more than just a monument with its life and night.

Of course: not everything about Pasolini can be ignored on an existential level. It is legitimate, and even right, to seek a foothold in history. This can be useful. At least to recover, if not the truth, at least the complexity and, above all, the size of things. As long as you don’t look for the correct interpretation in any way.

The day after he was murdered, he was supposed to participate in the Radical Party congress. He would intervene as a communist, an admirer of the civil rights struggle. However, it asked the radicals not to transform themselves into the radical mass party that the PCI would soon become. To plead that they remain unrecognizable.

Thus, his will expresses, perhaps better than any other document, the potential for emancipation and, at the same time, the homologation inherent in the process of personal liberation. And this helps to discover, among other things, the double bottom that history sometimes produces. In this case you have to go through it, avoiding shortcuts.