Although there is still widespread rhetoric that depicts fossil fuel-based energy production as irreplaceable, the reality increasingly shows a different picture. In fact, fossil resources are increasingly uneconomical despite the direct and indirect subsidies that oil multinationals continue to receive from the state. This is reaffirmed by two analyzes published almost simultaneously – the Production Gap Report 2025 and a new report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) – which highlight a paradox that risks affecting markets, energy security and ecological problems: the productivity of existing reserves continues to decline and new fossil extraction projects are often carried out in areas so complex from a morphological point of view that they prove completely unprofitable except thanks to state incentives.

According to the 2025 Production Gap Report, twenty of the world’s major fossil fuel producers, including the United States, Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, and Brazil, are planning increased production compared to 2023. If these programs are implemented, overall production by 2030 will double compared to the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Only the UK, Australia and Norway forecast a reduction in oil and gas production by 2030, while eleven of the twenty countries analyzed actually increased their plans compared to 2023. This goal runs counter to what the IEA found in its latest analysis, which was based on more than 15,000 oil and gas fields around the world. The agency documented that global production from existing fields is declining much faster than expected. If detailed, the average European offshore field experiences leaks more than 15% of production annuallywhile shale production fell by 35% in the first year and fell by 15% in the second year. The IEA’s executive director, Fatih Birol, underlined that “almost 90% of annual upstream investment in the oil and gas sector is intended to compensate for the loss of supply in existing fields”. In economic terms, it’s about about 570 billion dollars per year spent solely to maintain current production levels.

And herein lies the real crux. The IEA calculates this, even though investment levels in existing oil fields remain high, between now and 2050 more than 45 million barrels per day of new oil production and nearly 2,000 billion cubic meters of gas from undeveloped conventional fields. In practice, to keep production stable, an increase equivalent to the combined production of the three largest oil and gas producers in the world is required. This picture seems to support those who support expansion: without new investment, fossil production will collapse. But the IEA’s own report underlines that this scenario is highly dependent on demand trends. If global warming falls as predicted in a scenario that meets the goal of holding global warming to +1.5 °C, then existing savings are sufficient and no need to open a new one. The “net zero emissions” scenario developed by the agency shows an accelerated energy transition decreased demand such as making the construction of new fossil infrastructure redundant. Therefore, on the one hand, the government is afraid of running out of reliable supplies and clings to the idea of new extraction under the pressure of industrial pressure; on the other hand, deposit realities and market dynamics mean that fossil resources require increasingly expensive investments and offer diminishing returns.

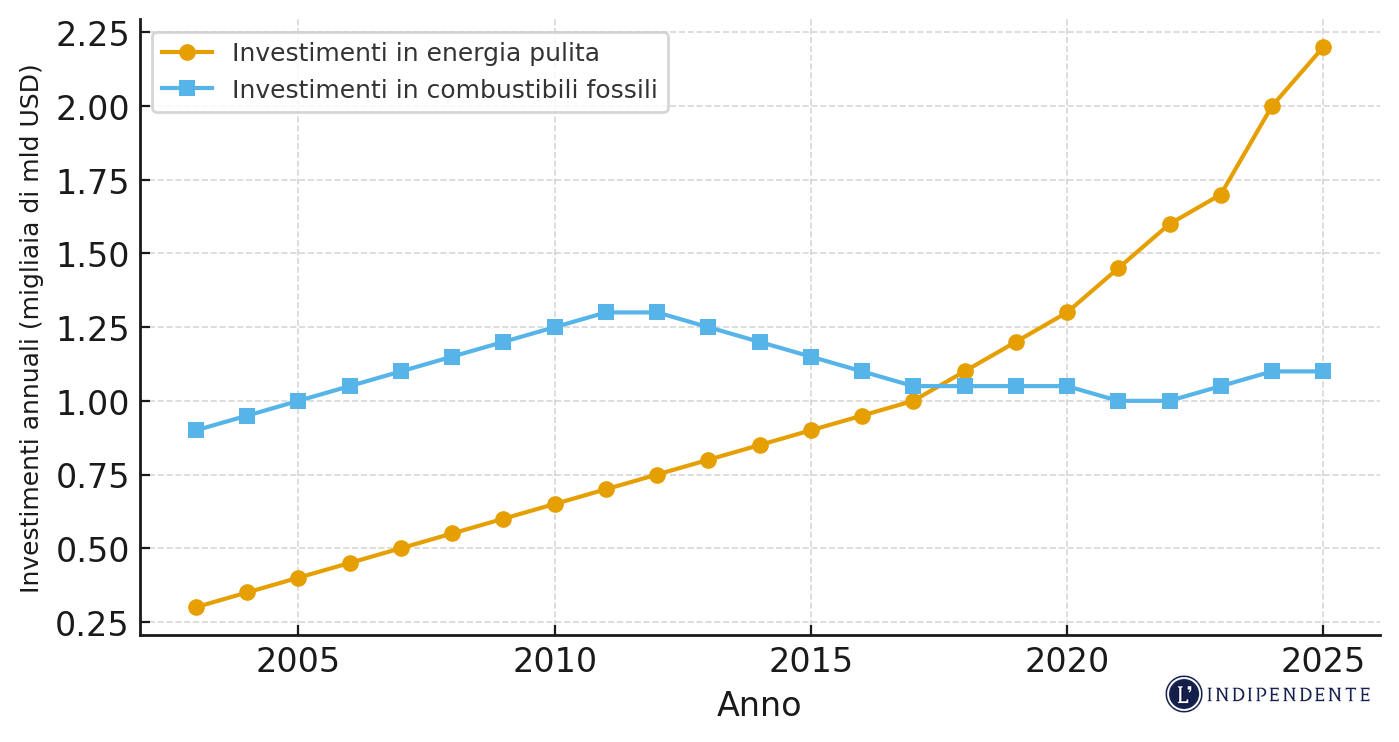

Meanwhile, the energy transition is accelerating. In a market-driven dynamic even though there is no definite public commitment. If you look where the money goes, the market is already voting with its wallet: The IEA estimates that by 2024, global investment in “green energy” technologies and infrastructure – renewables, grids, storage, efficiency – will reach around 2,000 billion dollars out of more than 3,000 billion in total energy investment, which is about double the amount still allocated to oil, gas and coal. By 2023, the curve has turned: for every dollar spent on fossil fuels, about 1.7 dollars is spent on green technologies worldwide. In the electricity sector, investment in green technologies has actually outpaced investment in fossil fuels by 10 to 1. The picture is therefore clear: governments are announcing expansion plans that risk undermining climate goals, while the fossil fuel industry faces a structural decline in reserves and unsustainable costs to maintain the status quo. However, the actual direction of travel seems to have been marked. Investors, driven by economic logic and not external pressure progressively abandoning fossil fuels supports renewable energy.