“Nothing has changed, but everything is different half a century later,” reflects Juan José Escribá, 76, as he scans the dunes from an SUV on the road to the northern border of Western Sahara. In 1975, this Valencian pensioner was completing his compulsory military service after completing his studies in Economics. “We didn’t know what was happening until they ordered us to evacuate the territory,” he recalls shortly before this Thursday marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Green March, the massive human mobilization with which Morocco forced Spain to leave its last North African colony. He is going to meet Mohamed Zuita, 73, a nurse who has arrived from Marrakech to join the Green March in Tarfaya (100 kilometers north of El Aaaiún, the Saharawi capital). “We were not afraid. They told us to cross the border because the Spanish military had retreated,” he recalls, now retired, once in Tarfaya, from where a wave of more than 350,000 Moroccans set off on the orders of the then King Hasan II, towards the nearby Sahara border line.

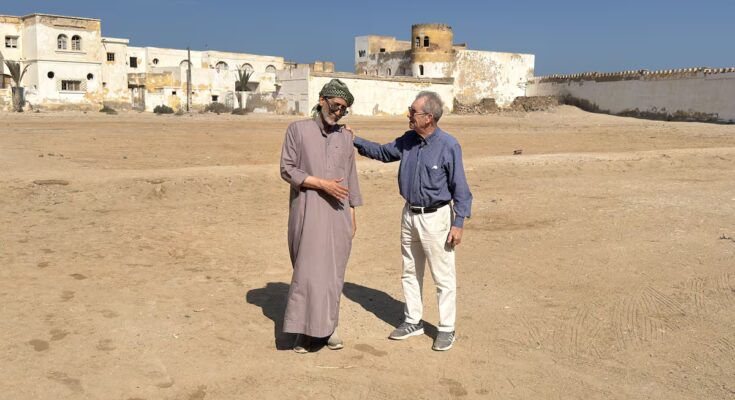

“I was in the rear, in the encrypted message transmission service,” Escribá replies as they share mint tea, “but if they had ordered me, I would have shot him.” After a few moments of initial tension, both greet each other affectionately in what was the Tarfaya barracks, known as Villa Bens at the time of the Spanish protectorate over southern Morocco, which lasted until 1956. They share the experiences of veterans on a historical milestone that still marks relations between Spain and Morocco. Evacuated at the beginning of 1976 as part of the so-called Operation Golondrina, through which more than 60,000 civilians and several thousand soldiers left what was province number 53, the former Spanish soldier retains a vivid memory of the Green March. “I have visited this territory about twenty times since 1975, and my library in Valencia has more than 150 books on Western Sahara,” clarifies the Spanish economist.

“I stayed to live near the Sahara to work in the military hospital and here I created a family after the Green March. I consider myself as much Saharawi as Moroccan”, says the former nurse Zuita near the Antoine Saint-Exupéry Museum, which recalls the presence of the French writer and aviator at Tarfaya airport between 1927 and 1929. “We crossed the Tah border (which separated the Sahara under Spanish control from Morocco) on November 6, 1975. There were no soldiers and the minefields were marked in Spanish and Arabic. We reached an area located about seven kilometers from Daora (20 kilometers south of the border), where the Spanish soldiers had gathered,” he underlines. “We stayed there until 9 (November), when King Hassan II gave the order to return.”

On the way to El Aaiún, the seventy-year-old Escribá carefully visits the ruined barracks of the Daora fort, which recall the pop decorations of the seventies of the last century on the walls of the troop canteen, and one by one he reviews the coats of arms of the different units of camel drivers and nomadic troops in the service of the Spanish army. Then he thinks about the coded messages he had to send on orders from his superiors about Operation Marabunta, the Spanish army’s defensive plan to try to prevent the passage of the Green March into Western Sahara. “I mostly dealt with classified documents, but I also got my hands on a top secret text requesting the sending of hundreds of marines to the Sahara”, he recalls, freed from the silence mandate imposed on him by his commanders, which obliged him to burn the documents once transmitted and not to discuss their contents with his fellow soldiers. “These barracks were called catenaricos,” explains the former soldier, in reference to the modular constructions with ovoid vaults characteristic of Spanish military architecture in the Sahara. Now they are structures threatening ruin in an area abandoned by Morocco.

Death rattles of Francoism

In the throes of Francoism, Hassan II’s strategy to gain control of the territory of Western Sahara was successful in factalthough the UN continues to consider it “non-autonomous” or awaiting decolonization. Under the reign of his son, Mohamed VI, the United Nations Security Council just formally approved it half a century later, through a resolution with no dissenting vote proposing the territory’s autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty as the basis for a negotiated settlement of the Sahara dispute.

As Spain prepared to begin the process of decolonization in 1974, Hassan II rejected any possibility of independence for the then colony to avoid seeing his country surrounded by a state allied with Algeria, and in the autumn of 1975 he launched the popular mobilization of the Green March, which had the shadowy protection of the army and a formidable logistical deployment to move and feed more than 350,000 Moroccans towards the border Sahrawi.

Before the great Moroccan protest caravan began and while the dictator Francisco Franco was dying in Madrid, then-Prince Juan Carlos went to El Aaiún as interim head of state on January 2, 1975. From the meeting room of the Officers’ Casino, now Casa de España in El Aaiún, he addressed the military commanders in a speech in which he promised that the “prestige and honor” of the army would remain intact in the face of a foreseeable withdrawal of troops. pledging to maintain “the legitimate rights of the Sahrawi population”. Washington then warned Rabat to avoid a direct confrontation in the Sahara at all costs.

Returning to the Sahrawi border of Tah, a monument commemorates the visit of Hassan II in 1985, 10 years after the Green March, surrounded by Moroccan flags lining the modern highway that today connects the Sahara with Agadir and the road network of the Maghreb country. A hundred meters away, the desert sand seems about to swallow the Spanish colonial road and the stone monolith that marked the territorial watershed in 1975.

“It was a festive and patriotic march. We were unarmed”, recalls 50 years later the Moroccan nurse Zuita, member of the Moroccan nationalist party Istiqal. “There were almost no injuries, only some fainting among the elderly”, explains this participant in the Green March, a mobilization that remained in the Moroccan collective imagination as a milestone of national unity. Tens of thousands of Sahrawi supporters of the Polisario Front, which defends the independence of Western Sahara through self-determination, then went into exile in Tindouf, in Algeria’s southwestern neighbor, where most of them are still in precarious conditions.

“I don’t know what will happen in the Sahara. I don’t know national and international politics,” says economist Escribá, now back in El Aaiún after visiting the scenes half a century ago. “I only know that my experience as a soldier in the Sahara marked my entire life and that is why I returned here whenever I could,” he added at the end of a trip to commemorate the Green March which, as he predicts, “will not be the last”. “When we were ordered to board the military evacuation plane that was transporting us to the Peninsula at Villa Cisneros (now Dakhla),” sums up the deep sense of nostalgia that the Sahara left in its generation of conscripts, “almost none of us wanted to be the first to fly and leave this land.”