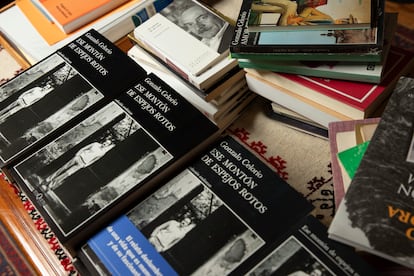

The Mexican writer Gonzalo Celorio, winner of the 2025 Cervantes Prize, uses in his memoirs a phrase that he says Montaigne wrote on the rafters of what he called the French philosopher’s ebony refuge: “Enjoy the present, the rest does not concern you.” The verse taken from Ecclesiastes could well define what Celorio (Mexico City, 1948) called the search for a Carpe Diem “winter”, that is, taking advantage of the present with the arrival of old age. “There’s little time left to enjoy life,” he says That pile of broken mirrors (edited by Tusquets), his recently published memoir which coincides with the Cervantes Prize.

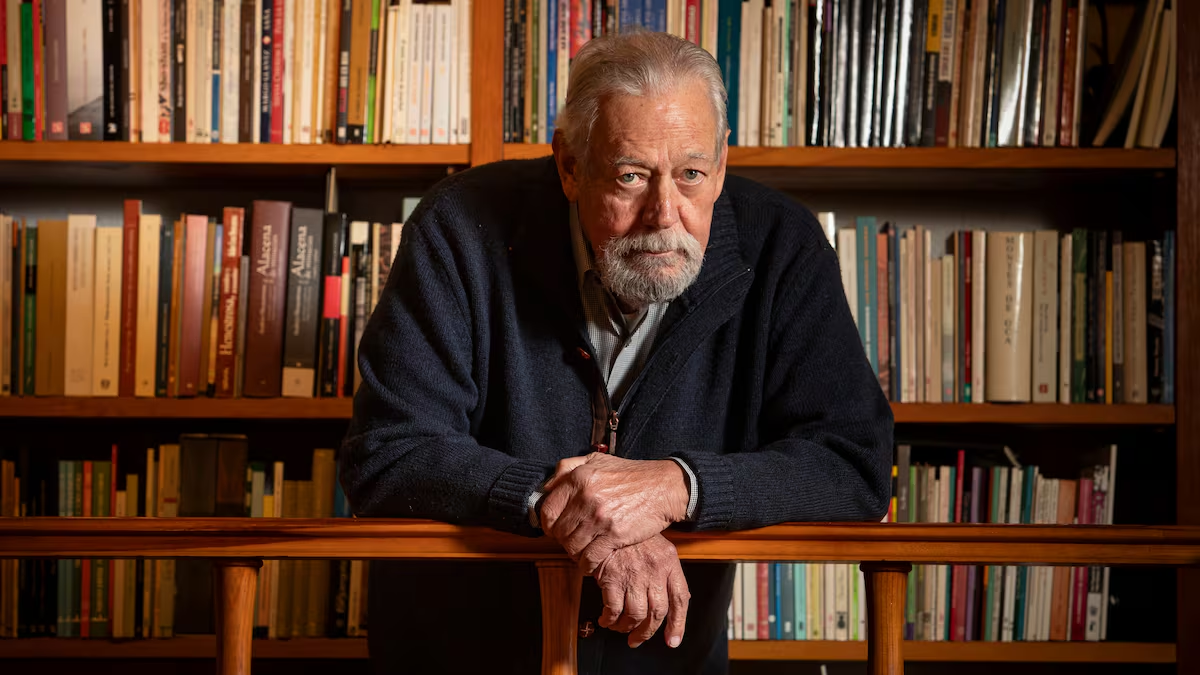

The writer, director of the Mexican Academy of Language, has retired from one of his passions, academic courses, but is still active in writing, to the point that the memoirs will be accompanied by a book which will be released to be presented at the end of November at the Guadalajara International Book Fair. Tireless despite the weight imposed by the years, Celorio talks about old age, his passion for words and his narrative creation in this interview conducted in the library of his home, south of Mexico City, a two-story enclosure with all the walls full of books, companions such as Balzac, García Lorca, Lope de Vega, Miguel Hernández, Juan José Arreola, Efraín Huerta, Rosario Castellanos, Juan Rulfo, Julio Cortázar and, of course the complete works of Miguel de Cervantes.

Ask. What does receiving this award mean to you?

Answer. I receive it with great enthusiasm, great enthusiasm and I feel that now I have to do it, to quote a Mexican myth, the Pípila syndrome, because I carry a large stone that represents the whole tradition of these awards given to such important personalities, whom I admire very much, and now I am in this cast and I hope I can live up to it.

Q. What does it mean to upload it? calculation for you as a writer?

R. This stone is like that of Sisyphus. That is, it also falls apart, but on the one hand it is something very pleasant, very happy, very stimulating and on the other it is a strong responsibility, because it implies a great literary commitment. I understand that I have lived this commitment all my life, because as someone said, I am a complete writer, because I have not only published essays and novels, but because I have also dedicated my life to teaching and academic research.

Q. Cervantes coincided with the publication of his memoirs. There is a concern for the future, he says that there is little time left to enjoy life and talks about a Carpe Diem winter. How do you live each moment now?

R. Him Carpe Diem He is still alive and perhaps much more current than when he was young, because when you are young you don’t notice the passage of time and you think it is eternal. But the temporal correlation between past and future is changing and before I had a lot of future and now I have a lot of past and that’s why I write these memoirs. I am a memoirist, not only in my works, where I explicitly talk about memory or present my memories, like this last book, but also in my novels, where there is a recovery of history, in this case a family history, but which also has a broader dimension.

Q. Why this interest in delving so deeply into memory?

R. We cannot know who we are if we do not know who we were or where we come from and who our ancestors are, what our historical determinants are. But I don’t do it just to recover the past, but also to understand the present and plan the future, even if this future evidently becomes scarcer every day.

Q. He also said that he writes to forget.

R. Yes, it’s kind of a contradiction. I always rely on a said by Juan Carlos Onetti who says: “Life is not over, there is still hope in oblivion”. I think this is important, because in the same way that you recover that history, you somehow exorcise it.

Q. In these memoirs he talks about death, first with irony and then with fear, both because of the covid-19 pandemic and because of the vocal cord cancer from which he suffered. Is that fear still there?

R. No, the truth is no. I have already accepted my condition, because with the pandemic many illnesses have come upon me, not only the discovery of this cancer of a vocal cord, which fortunately has completely regressed and that carcinoma was removed in time. After that, an illness that I had had for many years, almost 50 years, got worse, called Reiter’s syndrome, who was a Nazi doctor who carried out a large number of tests by injecting typhus in some concentration camps and killed many Jews. Now it’s called reactive arthritis, and it’s something that used to happen to me very sporadically and now makes me almost unable to walk, which is terrible because I’m a man with a great taste for travel and mobility. So the prospects aren’t exactly the best, but the spirit is still alive and enthusiastic, because for me the vitality lies fundamentally in the writing.

Q. In fact, he has declared that he will not retire until his strength and lucidity fail. What new projects do you have in mind?

R. This work that I have just finished has left me a little exhausted, it is like a rather bulky creature, it is an obese book, which I hope can walk well on its own. At the same time as this book, another one is coming out that I will present at the Guadalajara International Book Fair, which talks about a writer I loved very much, who has just died and who was a dear friend of mine. I am referring to Hernán Lara Zavala, a great connoisseur of English literature, also a magnificent essayist, as well as a novelist and short story writer. And so now, a little saddened, I wrote this book about him, called My friend Hernan. After giving birth to these twins, I now need to rest.

Q. Where do you draw the line between what you experience and what you invent?

R. There are no borders. The truth is that everything that is remembered, that belongs to the memory of what has been experienced, is somehow distorted by time and language, because language is not reality, it is a mechanism for learning reality. I believe that all historical literature is fictional, because there is no other way, the language is fictional. All literature is also, in some way, directly or indirectly, autobiographical.

Q. What risks are involved in transforming personal experience into narrative material?

R. There are no risks, on the contrary, I believe that rather a reality is created that is perhaps more real than the reference reality. It’s wonderful, the writing is finally creative and ends up building a world that can have more vitality, more validity, more realism even than what served as a starting point.

Q. His prose is recognized for its attention to language. How is your work with words?

R. Carlos Fuentes once told me that I wanted style. And he also said that if a novel didn’t want style, he wasn’t interested. Because in fact style is the limit between the verb and the flesh, said one of these French theorists who were in vogue a few years ago. Style is a way that defines us, that represents us, that distinguishes us from anyone else, because style cannot be copied, you can have a style with many influences, because a writer is generally also a reader. My style has to do with the ability to exacerbate the possibilities of the language in the richest and most fruitful way possible, because what I hate a little is the limitation, the punishment of the language when there is extraordinary richness and very few words are used.

Q. What role do humor and irony play in your writing?

R. They are a couple of important elements, of course, because irony implies the return from things and the return is more parodic and the parody is often an homage. I have a couple of books that make up the collection of my essays, which are called From the race of agewhich is a verse from Quevedo. In the first essays there was not yet this malice, this historical awareness, to be able to overcome the irony, which is what happens in the second volume.

Q. How much of that mischief is there in your work now?

R. There is no writer who is not mischievous. There is no such thing as a naive writer. Naivety may be suitable for the lyrical genre, but not for the novel. The novel is a dirty genre. This is how Carlos Fuentes described it. If we tried to subject the novel to a clean canon, it would be an anorexic genre, because the novel feeds on all facets of reality, the wonderful and the terrible, the disgusting, the despicable.

Q. When do you decide that a novel is finished?

R. The fact is that a novel is not finished, it is abandoned. That is, you feel that you have already traveled the path you were supposed to travel. Writing a novel is a very arduous exercise, because it requires discipline and perseverance. This is the big difference between the novel and the short story. Juan José Arreola said that a story is like a diamond, but a novel is the story of the search for that diamond.

Q. What does this research look like in your case?

R. I have almost no preconditions before writing a novel. It’s like diving into the sea without wax in your ears and being ready to hear the sirens singing. It’s a great adventure and you don’t know in that adventure what will happen to you. A novel is constructed in a constant, but less predetermined way. There is nothing predetermined in a novel.

Q. He said that the Spanish exile was his great teacher. How did it influence your education?

R. Many of my professors, when I entered the faculty, came from Spanish exile, they brought with them the impulse of the republican attitude, the seed of rebellion against a dictatorial imposition like that of Spain throughout the Francoist night. And these teachers were very formative for me. One of them was Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez, a great philosopher who arrived on the ship Sinaia, where he published poems before philosophical texts. He was a young 19-year-old who was so shy that he didn’t sign them with his full name, but with his initials. My teacher was also Ramón Xirau, a person who combined philosophy and literature very well, he was a great poet in the Catalan language. And Luis Rius, who was a wonderful teacher of medieval literature. They really had a didactic ability in making us understand and appreciate, appreciate medieval Castilian literature, which was wonderful.

Q. You also said that the novel is a libertarian genre, why?

R. The first novel written in America is The mangy parakeet of José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, the Mexican thinker, who wrote many texts, who was a great journalist and who suffered many prisons in the colonial era, at the end of the viceroyalty. When the Cadiz Constitution of 1812 was promulgated, which guaranteed freedom of expression, this man was removed because he could no longer be censored. And then he writes the first novel of the entire continent. I think this will be the topic of my award acceptance speech, how Cervantes was betrayed here, because the novel was not considered an edifying genre, it was considered a very dangerous genre, because the novel is subversive. A novel is something that always reproduces reality, but always adopts a critical attitude towards that reality and this obviously could not be allowed at the time of the viceroyalty, which is why I say that more than a literary genre it is a libertarian genre.