The early years of the thirteenth century will see a fundamental event in Europe that will mark a new course for science, commerce and the economy in general. It was then that Leonardo da Pisa, nicknamed Fibonacci, returned to his hometown after spending his youth in the commercial enclave that that northern Italian republic had in the Algerian port of Bejaia. Upon his return, this mathematical genius and popularizer in Europe of the sequence that bears his name published the Free Abacian essay or proposal on mathematical calculation which marked the introduction of the so-called Arabic numbers into the Old Continent and the replacement of the cumbersome Roman system which provided for only seven digits. And furthermore, a fundamental flaw, it didn’t know zero.

But the nine numbers and the sign that facilitates the understanding of thousandths, tens or hundreds were already in daily use no less than in the third century BC in what is now the Indian state of Bihar, when it was the center of a powerful Buddhist nation ruled by Emperor Ashoka, one of the great names in the history of India.

The Indian numbering system expanded from the 8th century onwards. It would arrive in Europe 500 years later

It was from Baghdad, the largest center of knowledge in the world, much later, when in the 8th century the Indian numbering system began to expand throughout the lands of the Caliphate and would reach Europe 500 years later, thanks to an Italian who probably did not know that, in reality, the origin of these numbers was not Arabic. The Scottish historian William Dalrymple (Edinburgh, 1965) argues in his new book The golden way (Dessaferro), that this Hindustani origin of the current numbers is just one example of the enormous legacy that the world has received from Indian civilization and which today is little known in the West.

If in his previous works, Anarchyone of the most brilliant and documented essays ever published on the plunder carried out by the British East India Company in just two centuries in India and in what is now Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, Dalrymple proposed bold theses, such as the comparison between the methods of the largest private business corporation that has ever existed and the current technological ones presided over by unscrupulous aspirants to become masters of the world, in The golden way His entertaining and erudite writing aims to reveal the enormous and largely forgotten influence that India exerted throughout the ancient world. Thus, from 250 BC until the 4th century, Indian sailors took advantage of the monsoon winds to develop a fluid trade with Rome, much more intense after the conquest of Egypt by Augustus, since ships from the Malabar coast and Tamil ports arrived at its coastal enclaves on the Red Sea and in which, in addition to pepper and other spices, precious stones, cotton and silk, ivory or sandalwood and other precious woods – which were exchanged for large quantities of gold – ideas, inventions and even the gods of India also traveled.

Dalrymple abounds in this new work on India, his adopted country, which was India and not China, as most historians have disclosed, which maintained intense exchanges with Rome in antiquity, not only commercial but inevitably also cultural. Therefore, thousands of Roman coins have been found in the ancient ports of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, unlike the few found in China. Indian museums, in fact, are those that conserve the most coins in the world outside the territories dominated by Rome.

But since the fall of the Roman Empire, explains Dalrymple, who lives between Scotland and New Delhi, ships of the Chola kingdoms and other southern dynasties once again turned the bows of their fleets eastward in search of gold, and the gold route expanded into what is now Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, China and the Maldives.

At this point he draws a similarity between Greek colonization in the Mediterranean and that exercised by India in Southeast Asia, both fundamentally cultural and not military. In the same way that Greek ships exported across the Mediterranean a language that preceded Latin, the gods, the architecture or Iliad and the OdysseyIndia spread Sanskrit from Afghanistan to the Far East, which would become the lingua franca in this vast area, Buddhism, Hinduism and style in temple construction. And still today the Ramayana and the MahabharataEpic poems as sublime as Homeric ones are performed in their native forms in Thailand, Cambodia and Indonesia.

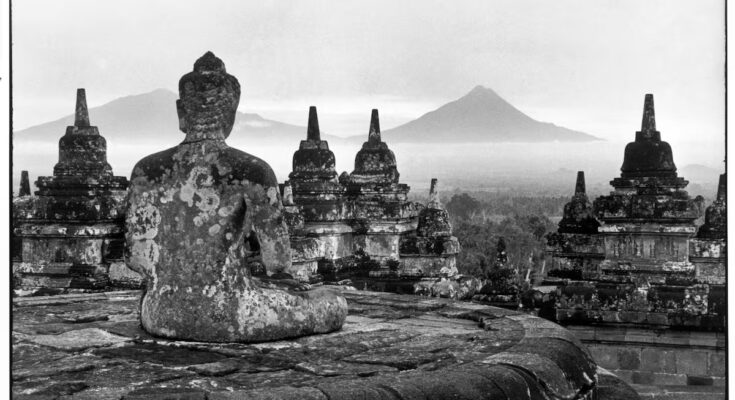

The largest Hindu and Buddhist temples that remain almost intact today – Angkor Wat and Borobudur – are not found in India, but in Cambodia and the island of Java (Indonesia) and, while undoubtedly incorporating local elements in their construction, both were designed according to the architectural canons invented in Mother India, as well as hundreds of archaeological remains of shrines scattered throughout the East: My Son and the Cham towers in Vietnam, the temples not only Angkorian, but also those built during the Kingdom of Chenla in the first centuries of our era in Cambodia, the sacred Sivaite enclaves in Nepal, the Buddhist cities of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa in Sri Lanka, the sculptures of Shiva and Vishnu in Lembah Bujang (Malaysia), the splendid archaeological sites of Ayutthaya and Sukhothai, in Thailand, the missing Buddhas blown up with dynamite by the Taliban in Bamiyan, the few remains saved by the zeal of other fundamentalist regimes, such as the Maldives, and even the inscriptions and statues of Hindu gods in Turpan, in China’s Xinjiang.

It was this country, and not China, that maintained intense exchanges with Rome in antiquity.

William Dalrymple is a brilliant narrator, he has an erudition already demonstrated in his previous works, almost all set in the Indian subcontinent, he has overwhelming documentation —The golden way It contains almost a thousand endnotes and the bibliographic index occupies 50 pages – and is narrated in a style that is agile, entertaining and easy to understand despite the complexity of the topic.

If it was not this historian who coined the term indosphere, he is one of the first authors to use it to explain “how ancient India transformed the world”, as we read on the beautiful cover of the Spanish edition of this essay. An influence that prevailed in Southeast Asia well into the 13th century.

The reason for this erasure from history of the enormous importance of Indian culture in the world since the first centuries of our era is attributed by Dalrymple to the racism and justification used by the leaders of the British East India Company from their offices in London and since 1858 by the government of Great Britain itself to legitimize a ruthless colonization of one of the two major cultural powers of Asia. How can we maintain a supposed civilizing mission if we admit a stratospheric cultural and economic superiority of the colonized in the past?

It is reminiscent of William Dalrymple in earlier works, such as The White Mughalsabout the first English and Scots who settled in India and were fascinated by their new homeland – many even married bibi, Muslim princesses, changed religion and adapted their clothing to the climate of the tropics – how in the 17th century the Mughal emperor Jahangir, the richest man in the world who reigned in the country with the highest GDP on the planet, saddened by the inelegant aspect of a mission arriving from the far West, granted the envoy of a small and unpleasant kingdom of Europe, Sir Thomas Roe, the privilege of establishing a small trading post at Surat (Gujarat) for the exportation of the riches of India by a few modest merchants. The rest of the story, as it happened in ancient Burma, Hong Kong or the Malay Peninsula, was the successive violation of agreements with a country’s rulers that allowed their business to finally impose its own laws and rule through the rifles of a powerful private army.

The golden way It is also a new example of the author’s love and fascination for the culture that was born “in the land north of the seas and south of the Himalayas”, the wise Vyasa tells us in the book Mahabharata. And there William Dalrymple identifies “the garden that produced the seeds that, planted elsewhere, would flourish with innovative, prosperous and unexpected results”.

The Golden Way: How Ancient India Transformed the World

William Dalrymple

Translation by Ricardo García Herrero

Ironwake, 2025

464 pages, 27.96 euros