Eskil, one of the sons of Cuban artist Wilfredo Lam (1902-1982), says his father was famous and unknown at the same time. Lam’s life, like his work, was complex and therefore difficult to summarize and classify, which meant that he was long treated as a marginal figure within the history of Western art, despite being one of the pioneers of modernism. Now the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York wants to pay him the well-deserved homage he never had during his lifetime. When I don’t sleep, I dream (When I don’t sleep, I dream) is Lam’s first major retrospective in the United States and the exhibition with which Christophe Cherix debuts as the new director of MoMA.

Although the Havana Museum of Fine Arts refused to give up the works for the retrospective, the curatorial team managed to collect more than a hundred of the most significant pieces to reconstruct Lam’s artistic career. Paintings, drawings, collaborations, books and a short documentary on the artist. The biggest attraction of the exhibition is Large compositionLam’s largest and most ambitious piece (4.2 meters wide by 2.7 meters high), which has not been seen publicly for 62 years and which the museum has just acquired from a private collector after several years of negotiations. It is a work that differentiates it from other previous retrospectives that have taken place on the artist (at the Pompidou Museum and the Tate, in 2015 or at the Reina Sofía, in 2016).

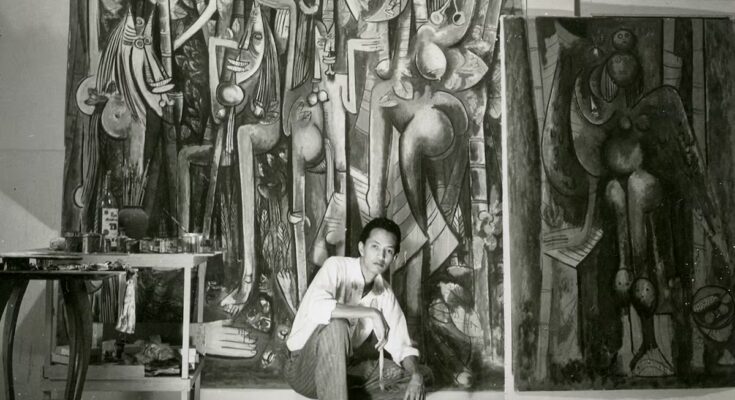

Lam, an example of a transnational artist of the 20th century, described his art as “an act of decolonization” and changed his style depending on the context in which he found himself. He didn’t have an easy life; Among other dark events, his first wife and firstborn died of tuberculosis. He was surprised by the civil war in Spain, where he went to study on a scholarship at the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, and enlisted on the side of the republicans, guided by the moral duty to fight fascism. There he composed The civil warhis largest painting to date, commissioned for the 1937 Spanish Pavilion at the Paris International Exhibition. With the arrival of Franco he moved to Paris, where he became friends with Picasso, Matisse, Joan Miró and Max Ernst, among others. He painted tirelessly: “So much so that my little hotel room was full and I could barely move.”

All was well, even shortly after her arrival, in 1939, she had her first solo exhibition at Galerie Pierre, where she exhibited several works exploring motherhood. One of them, mother and son, It was purchased by MoMA and became Lam’s first painting to become part of a museum.

But the Second World War broke out and, with the German invasion, Lam was forced to flee to Marseille together with other artists. There his friendship with André Breton will intensify and he will become part of the surrealist movement. He practiced surrealism, as he said, “to free himself from his worries and fears.” In 1941, at the age of 39, when he was denied entry to the United States and Mexico due to his closeness to influential figures on the European left, he returned to Cuba, having spent nearly two decades in the diaspora.

In 1945 MoMA acquired The jungleone of the first works that Lam created upon his return to Cuba. It is a work in which the human is intertwined with the plant and the animal. A painting that is not made on canvas, but on kraft paper and with thinned oil to make it last longer, as the artist had to come up with creative ways to cope with the shortage of materials.

the jungle It was displayed for many years in the museum’s atrium and became Lam’s best-known work. “But there are many relevant pieces before, and many relevant pieces after that work. It was necessary to expand the perception of Wilfredo Lam,” clarifies Beverly Adams, curator of Latin American Art at MoMA and curator of the retrospective. “He left an impressive legacy both in Europe and the Caribbean, in South America and the United States. He was a source of inspiration for many artists and his art transcends geographies: it encompasses power and colonialism, poetry and politics, diaspora and modernism.”

In Cuba he reinvented himself, reconnecting with Afro-Caribbean histories, something that was strongly influenced by the friendship he established with the Cuban writer and ethnographer Lydia Cabrera. His work was full of symbolism and hybrid figures that represented transformation, such as horse-women, plant animals or mutating birds. “I knew I ran the risk of not being understood by the man in the street or the rest of the public, but a true work of art has the power to make the imagination work, even if it takes time,” the artist once said.

Lam never stopped believing in his art, or in painting. After the success of The junglehe traveled exhibiting around the world and, by the time he died of cancer at the age of 80, he had already had more than 150 exhibitions and was a respected artist. Yet, as Cherix points out, “the big problem with art history is that it tends to pigeonhole works and artists into labels, and Lam never quite fits into any category,” which explains why he wasn’t as well known in the general narrative of 20th-century art. That’s something that has changed in recent years, as global interest in his legacy has grown and many of the world’s leading contemporary art institutions have decided to do him justice.