Ever since the Mexican Maha Schekaibán, mother of five children, reported her ex-husband for physical violence and indirect violence, her life has been transformed into a sort of hell full of corridors, courts, judges, government agencies and public officials from which so far she says she has only obtained re-victimization, estrangement from her children and permanent fear. It has been almost two years of court proceedings since she filed a complaint of physical violence and 13 initial hearings have been cancelled, in what she sees as a suspicious stagnation in her case. The last suspension dates back to September 11, when the ex-partner’s defense requested an annulment hearing to invalidate key evidence in an attempt to further slow down the trial. By contrast, the criminal complaint her ex-husband filed against her in July last year for family violence, allegedly against their children, was successful enough to push the prosecutor’s office to seek 36 years in prison against the woman, and a judge agreed to attach her to the trial. Schekaiban’s defense lawyers believe that behind everything there is a systematic strategy of evading justice by his ex-partner.

In addition to the 13 hearings suspended for physical violence, the other complaint against the entrepreneur Bernardo Vogel Fernández de Castro, for indirect violence, has already seen the first hearing cancelled. In the meantime, the criminal proceedings against the woman proceed without obstacles. In the hearing in which Schekaibán was involved in the trial, which lasted more than 22 hours, the judge rejected all her evidence and a few days later, her investigative file disappeared for more than a month, preventing her from continuing with her defense, according to the victim’s complaint. Among the facts that support the accusation against her are the alleged blow to one of her daughters with a plastic bottle, a scratch on the arm of another of them, and the fact that she did not accompany her children to school for two days, despite having custody of them.

Maha Schekaibán and Bernardo Vogel, director of Grupo Collado and owner of companies such as Tenaris-Tamsa, Bitso, Ternium, Techint, EVSA, Operbus, Exximpro, Innovare or Novopharm, have been married for 18 years. EL PAÍS contacted the entrepreneur to find out his position in the case, without receiving a response. Grupo Collado staff confirmed that they had been informed of the interview request to which they decided not to accept.

Schekaiban and Vogel met at a wedding and married 11 months later. The two lived together in the United States while studying for a master’s degree at Harvard, and soon had the first of their five children: they are now aged 9, 11, 12, 13 and 15. The lawyer dedicated himself entirely to their education and care. She has been kept away from them by court order for 20 months and is on a supervised visitation regime. Schekaibán assures that, from the beginning, her ex-partner prevented her from pursuing any of her three professional training careers (industrial engineer, accountant, graduate in business administration with a master’s degree from Harvard). She also says her ex-partner exerted control, economic and psychological violence, as well as repeated episodes of infidelity during the nearly two decades the marriage lasted.

In August 2023, the complainant says, after more than five years of escalation of the family violence exercised by Vogel against her and her children, with pushes and beatings in fits of rage, she expressed her intention to divorce and then began this whole judicial ordeal that has brought her to the point that the Mexico City Prosecutor’s Office, at the request of Vogel’s defense, wants to give her 36 years in prison. “I tell him I want a divorce on August 22. He starts making his plan about 15 days after I tell him I want a divorce and uses that time to manipulate my children,” she says.

After 19 months of total separation from her children, she was recently authorized to contact them through guided visits to the Family Coexistence Center (Cecofam): once every 15 days, for 90 minutes. The visits are recorded and, according to her, the minors show clear signs of parental manipulation and alienation. “After all this time, I can barely see them for an hour and a half, under surveillance. There is no real coexistence, there is resistance and conditioning,” he explains.

Judicial network suspicions and political loyalties

Schekaibán denounces that in all these years a complex structure of political, judicial and economic power has worked against her – and in the case of other women – which operates silently in Mexico City, through the courts, the Prosecutor’s Office and some media to protect the attackers and neutralize the victims. “A framework that has allowed trials to be manipulated, files to be corrupted and impunity to be maintained in cases of gender violence and serious crimes,” she protests.

Just a few months ago, a video that began circulating online, recorded by one of the minors, showed her fighting and attacking her by hitting and pushing her children, in a scene filmed by a small camera that, according to Maha, was given to the children by her father to provoke a violent reaction in her and for that reaction to be recorded on video. In the scenes, the children show rejection of their mother and accuse her, an attitude that is repeated and which, according to the woman, responds to the manipulation that the father exercised even before deciding to separate.

Maha Schekaibán says she decided to make her case public given the risk she ran of being a victim of femicide. “I saved myself because I made it public. Killing me now is not convenient for them, their other move is to put me in prison”, he says, recalling some death threats he received. “I haven’t committed any crime, I haven’t done anything. I’ll go whenever I have to go,” he says.

A legal attack against women and their lawyer

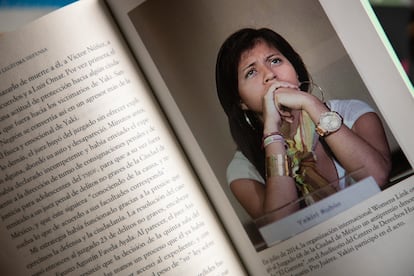

Schekaiban’s case is not isolated. In recent times, there has been a judicial offensive against women who have reported violence by men – who have the common characteristic of holding a lot of economic and political power in Mexico – and against the lawyer who represents them, Ana Katiria Suárez, who currently resides in Spain. At the end of 2024, Suárez, founder of the Voices Humanizing Justice AC association and legal representative in emblematic cases in Mexico, such as that of Yakiri Rubio – a young woman sexually abused in 2013 and jailed for killing her rapist – was accused of leading an extortion network made up of officials and some of those women who had denounced their former partners.

In addition to Schekaibán, the women criminalized so far include Regina Seemann, María Fernanda Turrent – already incarcerated – and Almendra Moreno, who will have a key hearing in the next few days and risks an attempted incarceration. According to the complainant, the men reported in connection with these cases appear to be in some sort of coordinated joint response to attack their former partners and discredit and criminalize their lawyer. “None of us knew each other before. Now we are all legally persecuted. This system is designed to subjugate the person who reports, not the attacker,” says Schekaibán.

The accusations against the women began in January 2025 with the lawsuit that Regina Seemann filed against her former partner Guillermo Sesma, brother of a deputy of the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM) and head of the Mexico City Congress. In this case, after several investigations, in addition to family violence, sexual abuse of minors was also reported. A campaign on social networks and some media positioned the complainants as members of a network, as it should have modus operandi take legal action against indirect aggressors to obtain millionaire compensation after divorce.

In a video call taken from Spain, Suárez assures: “This is a network of aggressors who protect each other. Justice in Mexico has been captured by economic and patriarchal interests. There are no untouchable aggressors, but there is a lot of power that buys impunity.” And he adds that there are many “women and children who have been terribly affected by the indiscriminate support” that the attackers receive from senior officials of the Superior Court of Justice in Mexico City. “Or rather, to those who can afford to pay them for their favors,” says the defender.

The lawyer, who from the beginning declared to trust the Mexico City prosecutor, Bertha Alcalde, states: “We know that the Public Prosecutor would never allow women who report violence to be criminalized. However, the operators of the Prosecutor’s Office and the Court continue to allow themselves to be corrupted by the economic and political power of these men, making effective justice difficult.” In the midst of all this, Schekaibán harshly summarizes what he has experienced: “If the other party has more money – as usually happens – they have already bought the judge, the prosecutor, the public prosecutor, the head of the Family Coexistence Center. This is not a personal case, it is an armed structure to punish women who dare to leave violent relationships.”