For almost 12 years, Oscar Centeno, driver of a high-ranking official in the governments of Néstor and Cristina Kirchner, meticulously recorded every trip he made with bags full of cash, proceeds of alleged bribes paid by construction companies in exchange for government contracts. He detailed times, routes, names and even the weight of the bags when he couldn’t calculate how many dollars they contained.

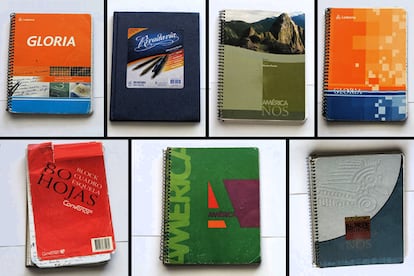

The notebooks in which he recorded all these trips were the starting point of the investigation that led to the largest corruption case in Argentine history: the so-called “notebook case”. The trial against Cristina Kirchner, allegedly responsible for an illicit corruption ring, will begin on Thursday, for which, among others, 19 former officials of the Kirchner administration and 65 entrepreneurs will be tried.

The former president, 72, is already serving a six-year prison sentence in a separate corruption case and has been under house arrest since June. He now faces potential sentences of between five and 10 years. His defense claims that “the sentence has already been written” because it is “a witch hunt” and “an act of revenge”, according to Gregorio Dalbón, Kirchner’s lawyer.

According to the prosecution’s indictment, the former president and her husband, the late Néstor Kirchner, organized between 2003 and 2015 “a fundraising scheme to receive illicit money in order to illegally enrich themselves.” To this end they established “agreements with important entrepreneurs of national and international companies, through which they obtained mutual benefits”. The indictment alleges that “the leaders and organizers of this parastatal structure designed a fundraising circuit focused primarily on the awarding and granting of contracts and/or public services and other related benefits.”

The legal matter focuses on the payments made to company executives, reported in the notebooks of the driver Centeno, on the mechanisms for awarding contracts for railway transport and motorway projects and on the cartelisation of public works. In addition to Kirchner, the accused include former ministers, secretaries, undersecretaries and state directors, as well as Centeno himself and another former driver, as well as executives of major construction, energy and transport companies.

The trips documented by Centeno, driver of an undersecretary at the Federal Ministry of Planning, came to light in mid-2018 in an investigation by Diego Cabot in the newspaper The nation; At the same time, the journalist provided the judges with the photocopies he had of the notebooks. The detailed scheme of Kirchnerist corruption hinted at in those notes was confirmed in the following weeks by several businessmen mentioned in them. They agreed to testify as cooperating witnesses in exchange for legitimacy.

Most of the repentant businessmen claimed to have paid money to Kirchnerist officials, but denied that this was in exchange for public works contracts. According to their testimonies, the funds delivered were supposed to finance the electoral campaigns of the ruling party and were in reality forced contributions obtained through extortion. This was the version given to the court by the repentant construction magnate Angelo Calcaterra, cousin of former president Mauricio Macri, and also by Aldo Roggio, owner of one of Argentina’s largest business conglomerates, Grupo Roggio.

Other defendants, however, admitted the systematic payment of bribes for contracts. Carlos Wagner, former head of the Argentine Chamber of Construction and owner of the Esuco construction company, provided the court with a list of companies that, through the Chamber, paid undisclosed sums of money to obtain infrastructure contracts. It further alleged that the illegal fundraising system had begun during the presidency of Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007) and had continued during the two terms of his wife and successor, Cristina Kirchner (2007-2015).

Years later, some repentant businessmen changed their story and asked for their charges to be dismissed, claiming that they had confessed to paying bribes under duress to judge Claudio Bonadio, who died in 2020. Construction company owner Mario Rovella declared before a notary in 2023 that he had lied in his court testimony to avoid prison, as Bonadio ordered pretrial detention for those who did not admit to the alleged crimes attributed to them, while releasing those who joined the “bargain” program reason.

Last September the accused entrepreneurs attempted one last maneuver to avoid trial. They offered the court sums of money up to $15 million, and even an apartment and a yacht in Miami, to be released from the case. Prosecutor Fabiana León listened to the offers and categorically rejected them: “There is no price that can be given to the institutional damage that has been caused.” Days later, the court ruled in the same direction and refused full compensation, finding that “corruption crimes affect supra-individual legal rights that cannot be compensated solely with money.”

It is assumed that during the trial the defendants’ lawyers will question the authenticity of the notebooks, the central piece of evidence in the case. Kirchner’s lawyers have already unsuccessfully requested that the case be dismissed because two expert reports found numerous alterations, deletions and corrections made by other people in Centeno’s notes. Last week, the Supreme Court rejected more than 20 appeals filed by former officials and businessmen, paving the way for the trial to begin.

Illicit financing of politics

According to experts, the importance of the trial goes beyond the alleged corruption during the Kirchner administration. “What is at stake is that, for the first time, what we all knew was happening behind the scenes is being discussed publicly,” emphasizes Pedro Biscay, founder of the Center for Research and Prevention of Economic Crime (CIPCE). “There is an underlying phenomenon: an institutionalized system of illicit financing of politics,” continues Biscaglia.

This corruption lawyer cites the exclusion of Techint executives from the trial as a prime example. Techint is Argentina’s largest economic group. Centeno’s notebooks record nine trips to the steel company headquarters. Nonetheless, the initial charges were rejected by the investigating judge, who accepted that Techint executives handed over money “for humanitarian reasons” to evacuate employees of Sidor, the company’s Venezuelan branch, which had just been nationalized. “The fact that a judge dared to say something like that explains that a corruption pact exists in Argentina,” he argues.

In theory, Biscay points out, this process offers the possibility that “not only will some corrupt individuals end up in prison, but that this criminal market will be undermined.” In practice, however, he considers it more difficult due to the complexity of a mega-trial with almost 90 defendants.

Martín Astarita, senior researcher at the Center for Studies on Corruption, Integrity and Transparency of FLACSO, also underlines the importance of carefully analyzing the role of entrepreneurs, who in previous cases have often been relegated to the background. “Corruption must be understood as a highly harmful relationship between the public and private sectors,” says Astarita. In his opinion, in recent years there has been an increasing takeover of the public sector by the private sector, which has gone almost unnoticed by the judicial system.

The trial will take place primarily through virtual hearings, broadcast via videoconference. More than 600 witnesses are expected to testify and the trial could last up to three years.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition