Juan Peiró survived at least three attacks. Between 1917 and 1923, a hidden war occurred in Barcelona between the bosses’ hitmen and the anarcho-syndicalists of the CNT, which was growing greatly and had Peiró as a leading member.

The employers, in connivance with the authorities, wanted to resolve the social issue by hiring mercenaries to assassinate union members. On two occasions the armed men of the gang The bench They searched for Peiró between work and home, but were unable to kill him. On the third attempt it didn’t arrive. He was supposed to meet at the El Tostadero café in Barcelona with the famous anarcho-syndicalist leader Salvador Seguí, nicknamed the We at Sucreand his partner Francisco Comas. Peiró didn’t arrive because he had dinner at home later than usual. He would join later, at the union hall. But, leaving the bar, in Cadena street, in the El Raval neighborhood, Seguí and Comas were shot and killed. “They would have killed my grandfather too,” says his granddaughter Amapola Peiró.

It is impressive to know the stories of that generation of trade union leaders who, in the first decades of the 20th century, fought against exploitation with everything against them: the bosses, the government, the Church, the bourgeoisie, the police forces, the entire system. They often ended up in prison, their families suffered from hunger during strikes (some died from illness or starvation), they suffered torture or were victims of attacks. But they continued. They had little to lose.

And one of those lives was that of Juan Peiró (also known as Joan), a leading man of the CNT. Now the book is published Juan Peiró, my father, an exemplary life (Salvador Seguí Foundation), written by his son José Peiró, who died in 2005. José’s daughter and Juan’s granddaughter, Amapola Peiró, 75, born and living in Paris, visited Madrid to talk about her family lineage. “I remember, since I was little, that my father wrote in his few free moments, because he had very hard jobs, the story of my grandfather,” she says. Amapola received this newspaper at the headquarters of the CGT union.

Juan Peiró, born in 1887, began working in the glass industry at the age of eight and remained illiterate until the age of 22, when he decided, as a self-taught person, to lock himself away at night to learn to read and write. “It humiliated him not to be able to read union leaflets,” says his niece, who defines him as a simple, extroverted, very talkative man, a lover of bullfights and pantomime. He became passionate about literature: he published several books, countless articles and edited publications such as The worker hive, The glass OR worker solidaritythe CNT newspaper.

He distinguished himself in trade unionism when, unexpectedly, he intervened in a meeting of the Costa i Florit glass factory to defend a fired colleague, and that path led him to be general secretary of the CNT and even minister of Industry in the Second Republic, already at war, in the government of Largo Caballero. “The two fundamental things that Peiró did as minister are the process of ‘nationalization’ or ‘socialization’ of large energy companies, not under state control, but under that of workers, and the creation of an industrial bank that would take advantage of the benefits of public industries to support those in deficit,” says Emili Cortavitarte, president of the Salvador Seguí Foundation. Anarchist and minister? “He never wanted to,” says Amapola, “he had to do it to obey union discipline: that’s how it was decided.”

That golden era of Spanish anarchism, which passionately mixed the purest ideals and the harshest violence, is the protagonist of various cultural products. The era of union gunfights is reflected in works such as the film The shadow of the law (Dani de la Torre, 2018) or novels The truth about the Savolta case (Seix Barral), by Eduardo Mendoza, Apostles and assassins (Gutenberg Galaxy), by Antonio Soler, o Let the stars be fire (Criticism), by Paco Ignacio Taibo II. They were imaginary lives and, therefore, could be transformed into novels; This is the case of the now classic The brief summer of anarchy (Anagrama), where Hans Magnus Enzensberger recounts the adventures of Buenaventura Durruti during the Civil War.

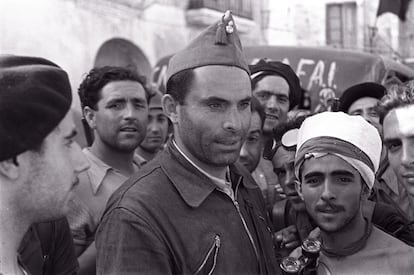

One of the great plots of Peiró’s life were the internal struggles, under the red and black flag of the CNT, between the faction of the “moderates”, revolutionary syndicalists or Trentists (from him Manifesto of the Thirty1931) and the radical anarchist faction of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI). Among the first, Peiró, Seguí, Ángel Pestaña. Among the latter, Federica Montseny, Juan García Oliver or Durruti. “My grandfather and his people didn’t want a CNT subservient to the FAI, they wanted the unionism of the working class world, people of any ideology and from any part of Spain, it wasn’t even necessary for them to be anarchists,” says Amapola Peiró.

Meanwhile, the FAI thought that the Trentists They moved away from the revolutionary essence of anarchism, falling into reformism, and here and there encouraged attempts at insurrection that usually did not end well (what they called revolutionary gymnastics). Example: the Casas Viejas events. Peiró thought differently. “He always said that for an effective and lasting social revolution it was first necessary to train the worker, who was capable of understanding what he was doing and who had a clear objective regarding the social structure. Libertarian communism could not be installed in a city overnight, as the Faists wanted. It had to be a transformation of society.”

The transformative example for Peiró was the workers’ cooperative Cristalerías de Mataró, which he directed and to which he devoted much of his vital efforts, since it was a sign that anarcho-syndicalist ideas could work. Founded by workers fired in other factories because they were undisciplined, everyone was paid the same, men and women, families kept their salaries even if the workers were imprisoned for political reasons (a common occurrence) and the children studied in a school inspired by the rationalist ideas of Francisco Ferrer i Guardia. Things weren’t easy. “Sometimes my grandfather got desperate because people didn’t go to meetings, they ignored the management of the cooperative,” says Amapola, showing a classic phenomenon of emancipation movements. But the cooperative worked and persisted. “He did such a good job that the Franco regime didn’t close the company, even though it didn’t continue like that. He continued to produce light bulbs until the 1990s, when he closed down due to competition from Phillips,” adds Amapola.

After the war, Peiró went into exile in Paris, where he coordinated the Junta de Auxilio a los Republicanes Españoles (JARE). Intercepted while trying to escape from Nazi occupation, he entered French and German prisons as far as Serrano Suñer, brother in law of Franco, took him to Spain. At the trial he was defended by several right-wing exponents, since he had always rejected the excesses and massacres behind the lines, described in the book Joan Peiró, afusellat (Editions 62), by Josep Benet. “The regime offered him to change sides and join Franco’s Vertical Union, but Peiró chose death rather than renounce his principles,” says Cortavitarte. He was found guilty on 21 July 1942 and executed three days later, together with six other CNT members, at the Paterna shooting range in Valencia.

What remains of those generations of illustrious anarchists? “We can find a reference in them, not to reproduce the same thing, because societies change, but to follow the idea that the working class must emancipate itself, and that it is not so much a question of leadership, but that the union must do a powerful job of both cultural and technical training. And there is a lack of ethics in current trade unionism. Peiró returned to his job after being a minister. We must be consistent with what we represent”, adds Cortavitarte.