“Via della Fontana”. “Via dell’Aria”. The names in Spanish of El Aaiún, founded 90 years ago by Spanish soldiers in an oasis, can be counted today, half a century after the Green March, on the fingers of one hand. Like public roads, official Moroccan administration buildings in Western Sahara are labeled only in Arabic and French. Like the Town Hall of the Sahrawi capital, inspired by desert forts. On the facade of the town hall located in front of the church of San Francisco, whose roof crowned by a cross evokes a sea of dunes on a desert horizon, an access has just been opened that radically alters its colonial architecture.

“The Spanish language, which is our heritage and part of our identity, is in sharp decline,” says Brahim Hameyada, 66, professor and director of the Unamuno Academy, the only center recognized by the Cervantes Institute in Dakhla, the capital of southern Sahara. “Like Hasanía (Arabic variety of the Bedouins of the Maghreb), Spanish should be recognized in a future statute of autonomy of Western Sahara”, defends Hameyada, who returned in 1992 to the former Villa Cisneros (colonial name) where he was born, after having served in the ranks of the Polisario Front in Tindouf (south-west Algeria). Today he teaches fifty students at his academy. “We do what we can so that the language is not lost, but in Dakhla there is no Spanish school.”

Spain’s legacy remains alive in the La Paz school in El Aaiún, the only institution that never closed its doors after the final withdrawal of the troops in 1976, shortly after the Green March. Although it was on the verge of closing due to lack of students, it always retained at least one teacher. Its current director, María José Navarro, 45 years old, has seen how the center has gone from just 70 pupils, grouped by four teachers in 2021, to more than 320 and 22 educators in this course, when it has already completed the entire offer of early childhood, primary and compulsory secondary education.

“We have a list of 312 membership requests that we can’t deal with,” acknowledges the director. “The demand for teaching Spanish has grown in the Sahara. Previously only the elderly spoke it, while adults were mostly educated in French and younger people now prefer English as a second language,” he explains.

Its center also contributes to the spread of Spanish with activities in which Sahrawi citizens participate, such as family school and story-telling sessions. To expand its training offer, it recently recovered a large part of the original headquarters, which had been annexed to integrate into an adjacent Moroccan institute after the Green March.

Except for the school in La Paz, every other official Spanish representation disappeared in the Sahara after the Green March until well into 1978, when the Spanish army took over management of the remaining state assets. Spain now has around 200 properties in former colonial territory, mostly homes of Spaniards who had to be compensated after being forcibly evacuated in the so-called Operation Swallow.

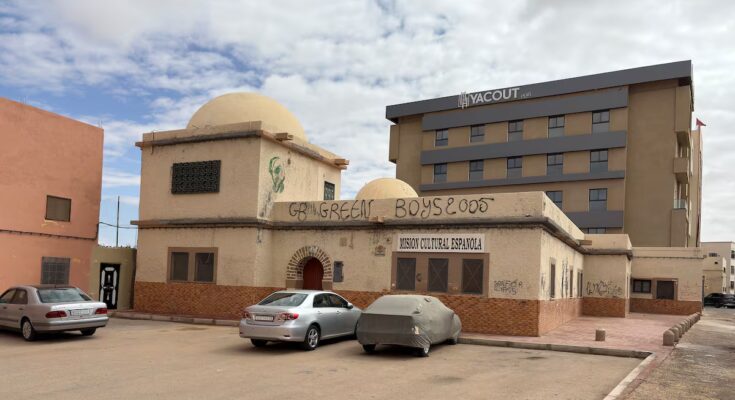

Currently, the Depositary of Spanish State Assets in Western Sahara, a non-diplomatic civil body that manages them, focuses its attention on the Casa España, its headquarters in the old Military Casino; the church of San Francisco de Asís, administered by an apostolic prefect (equivalent to a bishop), and the Spanish Cultural Mission, a building in a state of abandonment and threatening ruin.

The headquarters of the City Council and the Provincial Council of El Aaiún, where the last Spanish flag was lowered in the Sahara, and most of the Spanish civil and military buildings, such as the large Legion barracks, were transferred to Morocco in the Madrid Agreement, which sanctioned Spain’s exit from colonial territory after the Green March.

In the south of the Sahara, Brahim Hameyada invites us to safeguard the Spanish historical heritage also in Dakhla, where in 1886 a first colonial military fort was built, demolished by Morocco in 2005. “The Spanish heritage still survives in the lighthouse of Dakhla, in the church of Nuestra Señora del Carmen, or in the areas of the historic center of the city of the former Villa Cisneros”, explains Professor Hameyada, son of a Sahrawi soldier colonial-era nomadic troops.

Spanish seems to have become a residual language compared to French – which in turn declines compared to English among younger people – as the second language of the inhabitants of what was Spanish province number 53.

After the massive arrival of Moroccan citizens over the last half century, the use of Spanish is today more evident in commercial signs than in the speech of the Sahrawis. The status of a “non-self-governing” territory (awaiting decolonization) at the UN has prevented the creation of new educational centers and the opening of a Cervantes Institute in Western Sahara. Meanwhile, France has already announced the creation of a French Alliance headquarters in Laayoune during Culture Minister Rachida Dati’s official visit to the Sahara, which broke a diplomatic taboo in February this year. Since 2013, the Cervantes Institute has approved the project for the creation of an extension (affiliated center) in El Aaiún and the simultaneous opening of another similar unit in Tindouf (Algeria), where the Sahrawi exile camps set up by the Polisario Front are located.

In addition to acting as a cultural and educational center of the Spanish language in Western Sahara, the main objective of the Cervantes Institute of El Aaiún lies in the training of teachers and their certification for teaching the Spanish language.

“Part of our history”

A graduate in Hispanic philology, Sahrawi Gajmula Ebbi, 64, defends at all costs the preservation and maintenance of Spanish culture in her land. “It is part of our history. The current situation, with a single school, is not enough. We need a greater educational and cultural presence in the Sahara that recalls the harmonious coexistence that generally existed until 1975 with the Spanish.” Ebbi studied in the classrooms of the La Paz school. Like thousands of Sahrawis, she went into exile in the camps of the Polisario Front in Algeria before returning to El Aaiún to serve as a member of the Moroccan parliament for the Party of Progress and Socialism. He now heads the Sahrawi Initiative for Sustainable Development and Human Rights, one of the civil society associations seeking to open a horizon of understanding in Western Sahara after more than half a century of conflict.