When at the beginning of the year, in Popcaststhe music podcast of The New York TimesBad Bunny was asked if he was worried that many people wouldn’t understand his lyrics, the most listened to artist on the planet explained that even some Spanish-speaking Latinos lose some of their meaning, because he sings in street Spanish, deeply Puerto Rican. And, when they pressed whether he felt obliged to explain his songs, he ended by humming a memorable one: “I don’t care!” (“I don’t care!”), which has become a mantra for many of his followers.

The position of Bad Bunny (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, 31 years old) to make Latin culture and the Spanish language visible transcends personal preferences and acquires a clearly political connotation framed in the current American context. After Donald Trump returned to power, both official communication channels in Spanish and the requirement for federal agencies to offer assistance to people who do not speak English were eliminated. And currently, according to the Immigration Justice Campaign, 90% of people detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) are Latino.

For Puerto Ricans, singing in their language is not in question, because it is in Spanish that they think and feel and, therefore, it is an essential part of their identity. In his already iconic appearance in Saturday night live In October, the singer reiterated his stance on singing only in Spanish: “And if you didn’t understand what I said, you have four months to learn Spanish,” he said, referring to his highly anticipated and controversial appearance at show halftime of the Super Bowl next February.

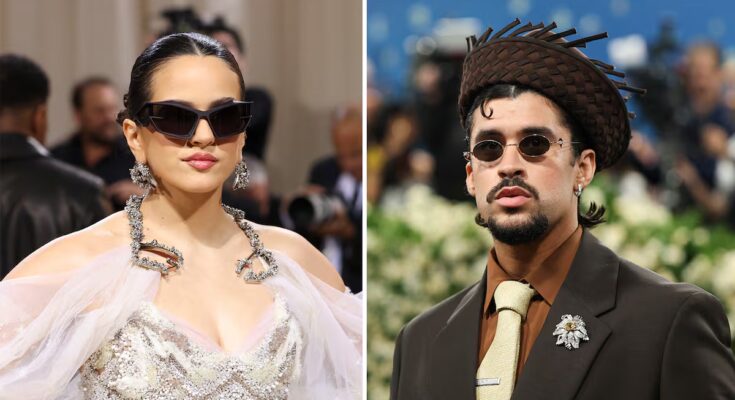

“I think I’m the opposite of Benito. For me it’s important. For me it’s so important that I force myself to sing in a language that’s not my own, even if it’s not my comfort zone,” Rosalía said last week alluding to the same question in the same podcast. A response which, apparently far from the intentions, was interpreted in a conflicting tone by the Spanish-speaking public and caused social networks to explode.

The singer herself addressed the controversy this week and responded to a video posted on TikTok in which a user of the social network accused the Catalan of taking advantage of Latin culture without understanding his background and stated: “(Bad Bunny) is making a political statement by choosing to sing only in Spanish. It’s something you can’t relate to, because you’re not Latin, you’re Spanish.” In a comment that she later deleted, Rosalía wrote: “I understand your point of view, but I think this has been decontextualized. I have nothing but love and respect for Benito, he is a great colleague who I admire and with whom I have been lucky enough to collaborate. (…) I have always been grateful to Latin America because, despite coming from another place, Latinos have supported me a lot during my career and I empathize with what you explain, which is why I am very sad that this happens. misunderstanding, because this was not the intention.”

On October 27, the Spanish company published Berghainthe first single from their fourth album, Lux (on sale Friday), an album of female mysticism in which she sings in 13 languages, including Ukrainian, Catalan, Sicilian, Mandarin, Arabic and Latin. “I belong to the world, the world is very connected: why do I wear a blindfold? It doesn’t make sense”, continued the artist, who says he dedicated an entire year exclusively to the lyrics of the songs that make up the album.

In the late 1990s, Latin and Hispanic artists who wanted to make their way in the musical world on a global scale were forced to change languages and sing in English, or to mix the two languages, as in the case of Ricky Martin, Enrique Iglesias, Shakira and Marc Anthony, creators of the boom Latin. Although the opposite also happened. Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States and many artists have wanted to reach the Spanish-speaking community by recording albums in two languages, as Jennifer Lopez, Christina Aguilera or, more recently, St. Vincent have done.

The debate over whether or not to record in a language other than Spanish dates back to the early 2000s. When Shakira began singing in English, Colombian singer Juanes (who has only recorded albums in his language), instead, walked around the Latin Grammys and MTV Awards wearing a T-shirt that read “We Speak Spanish.” At the time he was promoting his album my bloodwhich included songs that achieved worldwide success such as The black shirt. Along the same lines, other Hispanic artists, such as Alejandro Sanz, Luis Miguel or Chayanne, have never felt obliged to record an entire album in English.

“Latin artists have progressively acquired greater autonomy and repertoires such as salsa have stopped being simple entertainment to play a fundamental role in the recognition of the Hispanic community”, writes Eduardo Viñuela Suarez, professor at the University of Oviedo in his article Pop in Spanish in the United States: A space to articulate Latino identity. For the researcher, the boom of the nineties marked a turning point in the history of Latin music, becoming the expression of a more integrated and better positioned Hispanic community within American society. “In addition to breaking records for plays and views on platforms like Spotify and YouTube, this new generation of Latin musicians is being recognized at the Grammys and taking prominent places at major festivals, like Coachella, as well as powerhouse shows like the Super Bowl,” he writes.

“At the end of the day, I’m Latino. I think if I’m myself, I can conquer the world by being who I am and singing in Spanish,” Maluma commented in an interview with CBS before his performance at the Global Citizen 2020 festival, where he was the only artist not to sing in English. The Colombian stressed how exciting it is for him to sing in non-Hispanic countries and see how 30,000 people sing his songs in Spanish. An experience similar to the one Ricky Martin had when he sang around the world The cup of lifethe song he composed for the 1998 World Cup in France and which was number one in 70 non-Spanish speaking countries. “Imagine what it’s like to go to New Delhi and see 50,000 people in a stadium singing in Spanish? To me it was proof that you can conquer the world without singing in English,” said Ricky Martin.

“I think English-speaking audiences are more open to Spanish lyrics. How many non-Spaniards did you hear singing ‘Deeespaaaaciiiito’ in the summer of 2017?” Félix Contreras, co-creator and co-host of NPR’s Latin music podcast, Alt.Latino, says this over the phone.

Unlike the first boom that occurred more than three decades ago, the current phenomenon is characterized by artists asserting their identity and the power to sing in their own language. They no longer feel the pressure to adapt to English to conquer new markets; Instead, they impose their comfort and hope that the audience will come to them. It is the strategy of artists like Bad Bunny and Maluma, but also Karol G, Residente, Natti Natasha, Nicky Jam, Becky G, Bomba Estéreo or Silvana Estrada. “Young artists don’t face the same obstacles in terms of sales and audiences as Latin artists of the ’90s,” Contreras clarifies.

On the other hand, the approach to English, if there is one, no longer involves recording two versions of the same album, but rather the fusion of languages in a single song or collaboration with English-speaking artists. This creative convergence has allowed music in Spanish to cross borders, normalize its presence on the international scene and occupy a space at the same level as the English-speaking market.