A new green and lush lung for Rio de Janeiro, built on a massive outcrop of land reclaimed from the sea. This was the ambitious idea in the mind of Carlota de Macedo Soares (1910-1967). Better known as Lota, she was a tenacious Brazilian woman who fought against all odds to realize her dream of building a park for the people. This month, Flamengo Park celebrates 60 years of verdant beauty. The story of its creation is a Carioca epic full of twists and turns, just like Macedo’s personal life, marked by his stormy relationship with the American poet Elizabeth Bishop.

At first glance, it seems like Flamengo Park has always been there, with its bright green grass, tropical trees near Sugar Loaf, Rio’s iconic landmark that can be seen from all vantage points in the city. But 60 years ago the area was covered by the ocean. The park’s 120 hectares of greenery were in fact created from the rocks, debris and sand generated by the demolition of a hill in the center of the city and the construction of the tunnels that were then just beginning to be dug through the granite hills surrounding the city’s mark. In fact, the Cariocas simply call the park terrorwhich means “land on the sea”.

By this point, Rio had lost its capital status to Brasilia, but it did not want to be beaten in the race to modernity. The car was seen as the passport to progress, and a huge clearing was needed to build highways between the city center and its booming new neighborhoods in the south, such as Ipanema and Copacabana.

The governor of the newly formed state of Guanabara, (named after the bay on which Rio is perched) Carlos Lacerda, asked de Macedo, a close friend of his, to decide what to do with this enormous expanse of land. Lota proposed reducing the previous plan of building four highways to two, saving the rest of the space to build a tropical Central Park by the sea.

He created a working group and installed the best in his leadership positions. It was a largely male clique, from which two names stood out: that of the modernist architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy, who directed the urban planning of the site, and Roberto Burle Marx, in charge of the construction of the gardens.

Rio already had considerable green space in the city’s elevated region, the Tijuca Jungle, but it had historically functioned as a hidden space for bourgeoisie outdoor picnics. The city lacked a large street-level park for the masses, where workers could enjoy their Sundays with dignity.

In addition to green spaces, the team designed museums, outdoor auditoriums, a puppet theater and a runway for model airplanes. “It is an urgent and unprecedented project: it cares as much about the beauty and conservation of the landscape as it does about its usefulness. It puts human needs before those of machines, it dares to offer pedestrians, the marginalized of the modern era, their share of peace and leisure”, commented de Macedo in a 1964 article published during the final stages of the park’s construction.

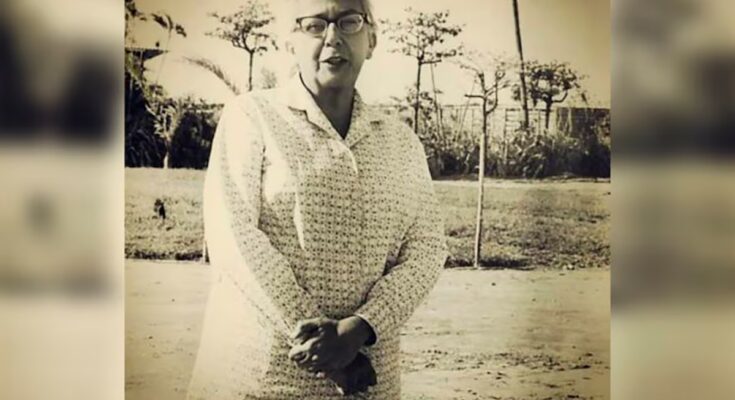

De Macedo grew up in a high society family, attended the best schools in Paris and Switzerland and studied painting with Candido Portinari. What he didn’t have was a college degree, but he had plenty of tenacity and a very clear idea of what he wanted. This was useful, because within her working group there were constant internal struggles, an abundance of ego clashes, says Claudio Machado, vice president of the Lota Institute, created by the woman’s fans to preserve her memory.

Joking Marx went so far as to call Macedo arrogant and authoritarian in newspaper interviews. “She was a woman without a degree who commanded a group of men and, what’s more, she was a lesbian,” says Machado in a bar located near the park. “She was everything that society at the time didn’t accept. But she was very incisive, she wasn’t afraid of anything.”

It was de Macedo who acted as a bridge between the creators of the project and the political world. His friendship with Governor Lacerda and his powers of persuasion were crucial in saving the project from pressure from the real estate industry, whose leaders dreamed of filling prime waterfront land with buildings.

Concerned about the future of the park, de Macedo managed to have the project declared a protected heritage site even before its opening. He also insisted on the creation of a foundation to manage the green space, to keep it safe from political interests. Its construction was a headache, but it also left room for pleasant surprises.

On one occasion de Macedo took advantage of the fact that Lacerda was on an official trip out of Brazil to take the project a little further than originally planned. He already had a dredger at his disposal that extracted sand from the seabed and did not hesitate to improvise a new beach in Botafogo Bay. Upon his return, the governor was furious that the project’s funds had run out, but he quickly reconsidered when he saw the joy in the neighborhood and the banners thanking him for his efforts.

De Macedo met a sad and premature end. When her friend Lacerda left state government in 1965, she was removed from management of the park shortly before its grand opening. This, added to a long list of disappointments, plunged her into a long depression that led to a three-month hospital stay.

He spent years in a complicated love triangle involving Mary Morse, his first partner, and Bishop, whom he met later in life. She also adopted a little girl with Morse named Monica, who would later be raised by the three women. Bishop gradually faded from the relationship, later returning to the United States.

In 1967, by which time the “landfill” park was the favorite of the Cariocas, de Macedo got on a flight to New York to try to win back his poet. Their meeting went worse than expected and the urban planner attempted to take his own life with an overdose of barbiturates. He went into a coma and died a week later.

With no one to defend his legacy, Macedo’s profile has faded over the years. (Another factor was its celebration of Brazil’s 1964 military coup.) What remains is the legacy of its park, a “resilient survivor,” as Fernando Nascimento, president of the Lota Institute, puts it. The institute is now planning an extensive program of events on summer Sundays to revive the park’s modernist bandstand. Rio city council is also completing some small extensions at the northern end of the park.

All these plans must be carefully planned, because in 2012 UNESCO declared the entire green space a World Heritage Site for its unique symbiosis of city, mountains and ocean. On Sundays, the avenues that run through Flamengo Park are closed to traffic and filled with locals walking, biking and skating. Barbecues, football games and colorful birthday picnics occupy every corner of its expanse. Even swimming in the sea is back in fashion, the waters are cleaner than ever after years of intense pollution. Security, always the park’s Achilles’ heel, has improved in recent years, and there are more and more visitors, even at night, when it is illuminated by the enormous 148-foot-tall streetlights (the tallest in the world at the time of their construction) that de Macedo designed, inspired by the zenithal light of the moon.

This illumination is rivaled only by the Talipot palms planted by Burle Marx, a species native to India and Sri Lanka that only flowers once it reaches adulthood, between the ages of 60 and 70. At that point, the trees suddenly die, leaving behind hundreds of thousands of seeds. This spring, the white tops of flowering palm trees peek out from the greenery of the park, a floral reminder that the lung of Rio de Janeiro has grown.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition