In 1989, Aaron Sorkin premiered the show some good menwhich was then brought to the big screen and played by some of the most recognized actors in American cinema. It tells the story of a lawyer who has to choose between honor or a bad deal. Everyone expects dishonor from him. But the script takes an unexpected turn and the lawyer ends up choosing honor. In history, the majority choose what is easy, but only a few choose what is right. These are the good men.

In recent years many academics are recovering some of these figures. The first part of the complete works of Concepción Gimeno de Flaquer was recently published (Prints of the University of Zaragoza). This 19th century feminist was a pioneer in the defense of women’s rights and the first to give a feminist lecture at the Ateneo of Madrid. Rather Catholic and conservative in thought, she had a problem: she was too feminist for conservatives and too Catholic for feminists. For this reason no one has claimed it to this day.

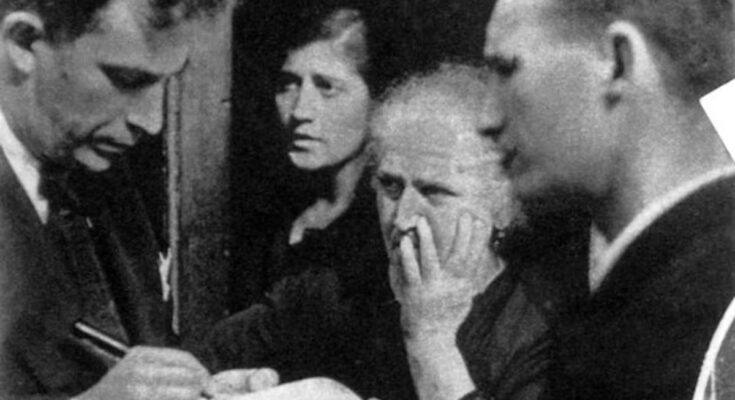

A paradigm of a good man is Manuel Chaves Nogales. He collaborated with numerous newspapers in our country until the end of the Civil War and then in exile. His chronicles give us a very truthful account of episodes such as the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, the Asturian revolution or the civil war. Furthermore, he interviewed people like Goebbels. But, as he wrote in In blood and fire: “I can say that a man like me, however insignificant he was, had earned enough merit to be shot by both sides.” His exile is a further example of his opposition to the Franco regime, which he detested. But if one reads Maestro Juan Martínez who was there, He will observe without too much effort the rejection that the Russian revolution of 1917 generated in him. A liberal man who put democracy and freedoms above fanaticism, he was never vindicated by any of them.

Joaquín Maurín is another example of a good man. He was general secretary of the Marxist Unification Workers Party (POUM) and a leading member of the CNT or Bloc of Workers and Peasants (BOC). Furthermore, he spent more than two years in prison under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and was imprisoned by the Francoists between 1936 and 1946, when he was pardoned and fled into exile. In 1958, he wrote to Ramón J. Sénder from New York: “What Franco claims is the failure of the Republic, a failure that nothing and no one can deform or erase. In 1929-1930, the Republic was a hope, that is, a promising future, now it is a disappointment, that is, a deplorable past.” Indeed, Maurín did not disagree too much with many of the republican exiles, as Juan Francisco Fuentes documented in his entrance speech to the Royal Academy of History, Wandering Numancia: the idea of Spain in republican exile. As Maurín ended up concluding in his correspondence with Sénder: “A liberal monarchy is desired, paradoxically, only by republicans.”

These are just three examples of good men forgotten by history. But, thanks to the work of historians and academics, their figures have recently been recovered. They all had two things in common. On the one hand, the defense of individual rights and freedoms. Regardless of the prevailing ideological currents, they understood that there were higher values to defend. On the other hand, since they did not take a fanatical position on their side, but also did not share the principles and values of their opponents, they repudiated them all. As Amos Oz reminds us in his short book Against fanaticism: “Not becoming a fan means being, to a certain extent and in some way, a traitor in the eyes of the fan”.

In today’s polarized Spain we witness experiences similar to those experienced by these good men. Today not defending any of the positions in an exalted and idolized way makes one a traitor. Many on both sides are accused of belonging to the enemy faction for not following the slogans or arguments. Today you become a suspect if you defend values such as your word, coherence or territorial equality. Everything is instrumental and everything is justified by the results it produces, without adhering to issues such as principles, ethics or morality. On both sides, something is acceptable if the desired returns are obtained, regardless of values and morality. When the future reaches us, many will remember those good men who reported that something was wrong. I think, for example, of Javier Cercas, a brilliant writer who in all his reflections reminds us that being on the left also implies having an ethical code, where the end does not justify the means.