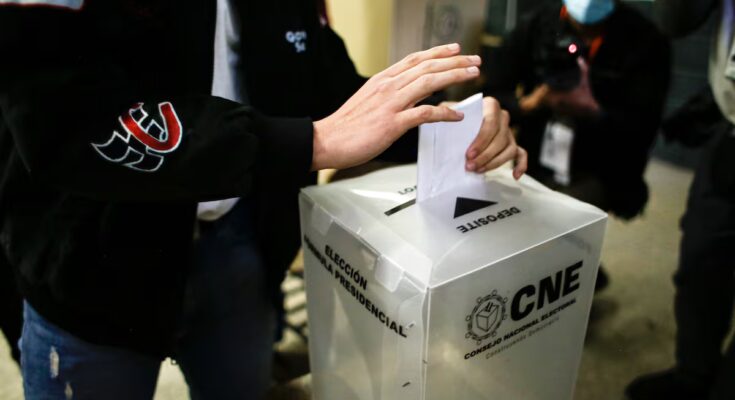

With less than a month to go until general elections for president, mayors and deputies, uncertainty reigns in Honduras. A political crisis is affecting the Central American country with a long history of electoral processes seriously questioned. The most recent coup occurred on October 29, after the Attorney General, Johel Zelaya, announced an investigation against a member of the National Electoral Council (CNE), an opposition MP and a soldier, all accused of organizing an alleged fraud in the November 30 elections.

Three days before the prosecutor’s announcement, General Roosevelt Hernández, chief of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the Honduran Armed Forces, held an impromptu press conference. There he reported that, on the same day of the elections, the military would ask the CNE for a copy of the minutes of each voting commission. His intention, he said, was to take them to a military base to “ensure the free exercise of suffrage and alternation of the presidency.” The request, which was not approved by the electoral body, generated a scandal among government critics.

The request coincides with President Xiomara Castro’s announcement that the military will be tasked with guarding election materials before, during and after elections, a measure required by Honduran law. “The Government has distorted what the law says. How is it possible that the request of the Armed Forces to carry out a count, a sort of control, is an absurd interpretation of the powers that the law grants them as guarantors of the security of electoral material”, César Espinal, Coordinator of the Observatory of Criminal and Anti-Corruption Policy of the National Anti-Corruption Council (CNA) of Honduras, told EL PAÍS.

After both announcements, on November 4, the Election Mission of the Organization of American States (OAS) in Honduras spoke out and called for adequate working conditions for the electoral authorities. “The EOM/OAS has observed actions and statements, virtually every day, that generate uncertainty and destabilize the electoral process,” the organization said in a statement.

Honduras is a country historically affected by violence, organized crime and corruption. In December 2017, former president Juan Orlando Hernández (2014-2022) won his second term in an election deeply marked by questions after the results of the vote count radically changed following a blackout. Hernández was convicted in June 2024 by a U.S. court of conspiracy to import more than 400 tons of cocaine and weapons crimes.

Experts warn that the Honduran government has cut funding to the Unit for Financing, Transparency and Supervision of Political Parties and Candidates, which could open the door for organized crime to fund politicians in the current race.

Who competes for the presidency

The November 30 elections will include the election of the president, mayors, deputies to the National Congress and representatives to the Central American Parliament (Parlacen). However, the greatest uncertainty and tension are concentrated in the presidential race. According to the experts consulted by EL PAÍS, there are at least three elements that have been generating uncertainty for several months: the questioning of the main electoral body, the widespread political violence and the thin margin between the three main contenders.

Although there are five candidates running for president, public opinion polls indicate that only three have a real chance of winning: Nasry Asfura, a Honduran politician and businessman linked to the construction sector. He was a deputy and then mayor of Tegucigalpa, the capital, for two terms, until 2022. In the 2021 presidential elections he ran for the National Party and obtained 36.9% of the votes. Rixi Moncada, lawyer and historical figure of Libre, the party in power, which she co-founded together with former president Manuel Zelaya and current president Xiomara Castro. Moncada was defense minister until May 27, 2025, when he resigned to run. And Salvador Nasralla, a former television presenter who became a political figure in Honduras. He was the first presidential appointee, a position equivalent to vice president, for most of Xiomara Castro’s government until he resigned in 2024. Upon his departure, he said he felt marginalized and had never held real office. He has competed for the presidency several times: in 2013, with the Anti-Corruption Party, which he founded, and in 2017, at the head of an opposition alliance. In the 2021 elections he withdrew his candidacy to support Xiomara Castro.

The polls released in Honduras paint an uncertain and contradictory scenario, where there is no clear favorite candidate and each polling station offers a different picture. For example, CID Gallup reports a technical tie between Salvador Nasralla (27%), Rixi Moncada (26%) and Nasry Asfura (24%), although this pollster’s credibility has been called into question after failing in 2021, when he engineered a victory for Asfura that turned out to be a big victory for Xiomara Castro.

The audio of the alleged fraud

During his press conference, prosecutor Zelaya, considered close to the Castro government, announced that he had opened an investigation against three people: the councilor of the National Party of the CNE, Cosette López; the nationalist deputy Tomás Zambrano; and an unidentified active member of the military. According to Zelaya, the three formed “an illicit association to alter the popular will, trying to impose a result in the presidential elections.”

The prosecutor played a series of audios to the press. In them we hear the voice of a woman who is said to be the councilor of the CNE, Cossette López. In the audio, the woman is heard talking to a man who, according to the prosecutor, is MP Tomás Zambrano Molina, an opposition deputy, member of the National Party of Honduras and alleged active military officer. After the prosecutor’s announcement, pro-government deputies and members of Castro’s cabinet spread the audio on social networks, which is why some government critics have denounced the tax investigation as an act of intimidation and campaigning in favor of the Libre party, the ruling party.

“There is the idea that the Public Prosecutor tries to favor the party in power. We have never seen such speed in dealing with complaints and in this case it was immediate. This leads us to think that there is a possible political persecution of opponents,” said Espinal, of the CNA.

6.3 million Hondurans are expected in the elections and, according to Espinal, the climate of uncertainty could lead to an increase in voter turnout and greater vigilance on the part of citizens. “We will have observers on site as the law allows us and we hope that the population will do the same,” he said.