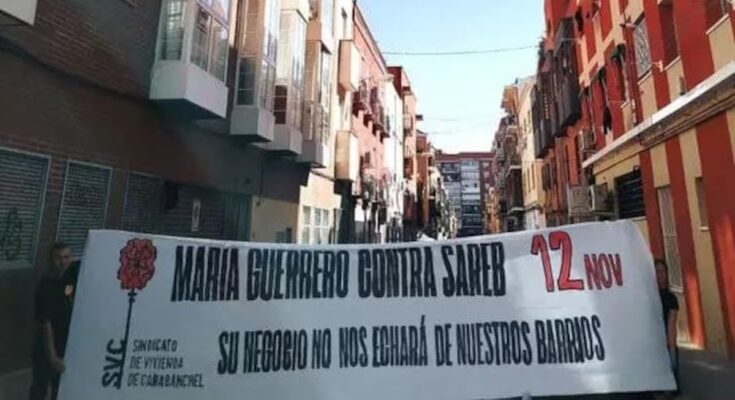

The history of María Guerrero 1 street, in the Madrid neighborhood of Carabanchel, is a collection in files of many of the ghosts that the house brings with it from the brick bubble. The latest episode, at least for the moment, is the eviction that six families suffered on November 12th by Sareb, the body created after the crisis to manage the toxic assets of the rescued banks. “I’ve been here for four years with my son, my partner, and finding and finding a room, one on one side, another on the other… is a bit complicated,” says Alfredo Remigio Abad, one of those affected. Another eight residents received a social rental proposal with clauses that they identified as unfair and decided not to sign it in order to reach collective bargaining. Sareb has divided these 14 houses into two groups, but the residents all go into one.

Abad looked for alternatives for what might happen, but found that they ask him 500 euros for a room, slightly less than the rent he paid for his house. Sareb took over the building together with the rest almost two years ago, after a mortgage foreclosure in the name of the building company of the block, a third party in dispute and fundamental to understanding this concrete tragedy. Inversions Winner SL built the houses in 2009 and put them up for rent. Like many things that happened in that period, it ended up as collateral for a radioactive loan that became part of the so-called bad bank’s portfolio at the end of 2012, and the owners continued to manage it with apparent normality.

Alberto Guío, the longest-serving tenant, arrived in the building about ten years ago, with a contract for a two-room apartment for 550 euros and the hope of having found something at a more or less reasonable price in his neighborhood. During the first few years he and the rest of the neighbors paid their rent by bank transfer. “Then the problem was that you could no longer access the account because it was blocked,” he says. From that moment on, it was the sole director of the company, from its creation in 2009 until 2013, Javier Bonmatí – who did not want to make any statements other than the fact that he no longer has anything to do with the ownership – who cashed in. “We paid him in cash, with a receipt,” Guío recalls.

Little by little the seams began to be seen; Something wasn’t right. When Guío wanted to register, for example, he couldn’t do it until the police arrived, because there was no property at that address and the block number in the contracts varied from one tenant to another. Furthermore, the deterioration of the building was accentuated. When Covid arrived, Guío says, the abandonment was total. In late 2023, a court ordered the foreclosure. The company collected rent through May 2024, and some receipts were occasionally accompanied by a “why do you want them?”

When the first eviction notice for the entire building arrived from Sareb, the question took on a new meaning: neither the proof of payment nor the contracts were of any use. The judge ruled they were illegal. Inversions Winner SL, like other heir companies of the real estate bubble, has left a trail of debt, people with one foot on the street and opened a new chapter for the community. With the exception of one tenant, who decided to leave, the other 14 organized themselves around the Carabanchel Housing Union to face the situation together. “All the people on the block turned to the court, leaving writings, saying that there were people who lived here,” recalls Andrea Cesaroni, a resident and member of the organization. The launch was interrupted and negotiations began, which ended with a proposal for regularization in the summer for eight homes and silence for the other six, including the largest, broken in October by the eviction notice.

Neighbors don’t know why there were different results for some and others: “Partly it could be due to disorganization,” Cesaroni says of a certain lack of control around Sareb’s leaders. “But then there is also the attempt to divide, to be there to put pressure, to say that I am the rules,” he adds.

The entity uses its protocols to explain the situation: they do not work with a single interlocutor, but individually, and the progress and result of the process, they say, depend on whether neighbors allow visits by officers and provide the necessary information. “There were eight families with whom we were able to work and who moved into our social area, because from the documentation and data that were requested from them it was seen that they were vulnerable,” underlines Sareb. “And there are six other homes that we have had no contact with.” They claim that they were not able to access those homes and that they did not provide the documentation at that time, documentation which, defends Miren Beriain, a member of the union and one of the members of its wing dedicated to Sareb, was sent more than a year ago and on several occasions.

He doesn’t rule out that it might have been out of place, but in that case, he argues, the response should have been to clarify it and ask for it again. “It’s like a very complex web, where it’s hard to pinpoint what the specific factor is, but ultimately there’s no will to find a solution,” he says. Sareb assures that he is studying the information received after the eviction notice.

The remaining eight apartments have obtained a social rent offer, but their owners denounce that these are poisoned contracts with many of the clauses that the building movement considers excessive. For Sareb it is “their way of seeing things”, and it fits them into the law. “At this moment we have signed 10,000 social rentals in Spain, exactly the same as those offered to people living in María Guerrero 1”, say sources from the institution. “They may be legally protected, but that doesn’t stop them from being abusive, because they give the landlord excessively more control over the tenant and leave him in a vulnerable position,” Beriain points out about the clauses. They should not, he says, be forced to sign out of fear or uncertainty.

The priority is to stop the eviction and then force renegotiation. They are asking for an agreement similar to that reached by numbers 11, 13 and 15 of the same street after Sareb sold them to the Municipal Construction and Territory Company of Madrid, and which provided for, for example, rental contracts adjusted to the value in use and not the market value. The body, which according to the union has already rejected the counter-proposal, ensures that the building falls “within the housing perimeter” which will be sold to the new public land company, SEPES, for social or subsidized rent. Furthermore, they underline, important work is expected when the contracts are formalized.

If a solution is not reached before November 12, the last resort is to try to stop it at the door. “The whole neighborhood will come,” says Guío. María Guerrero is not the only street affected by housing issues in the area and the mobilization ensures that a collective problem is not individualized. “Even those of us who are organized, who have been part of the union for a long time, feel that this has a meaning and a broader struggle than this building itself,” reflects Salma, another neighbor, who prefers not to reveal her last name. “This is a situation that occurs in many places in Madrid.”

Guío still remembers when he bought gummies in the corner shop, a low house that is now a new building, where, according to an ad on a real estate website, the square meter sells on average for almost 6,000 euros. «If you look around, you will see how everything that was a small shop is an apartment», says Cesaroni about the rooms converted for residential use and which can be recognized by the white doors. “Everything, all white doors,” he says with words that encapsulate one of the changes and problems the neighborhood is going through.