Guns, Jeans, Playmates – Bingo! Artist Lutz Bacher has been tearing apart American myths like an old machine. Their heritage is only understood in Europe.

Days burned: 71. 34. 4. 15. 62. 40. The numbers on the rectangular scoreboard are pale black and white, but every few seconds, at regular intervals, one of them flashes yellow. You have enough time to think about why this is the right time and wait for further fate. On the left edge of the board, a column of red letters forms the word BINGO.

But the machine doesn’t know whether anyone won, only the absent players here know. Someone drops the pen and screams, no one is happy with the small victory, the attention, the feeling of having found a glimmer of happiness from the chaos of the world. The bingo machines are part of the first retrospective dedicated to the American artist Lutz Bacher (1943–2019).

Bacher is the most famous unknown in contemporary art, an “artist’s artist” with much influence on other artists. Solveig Øvstebo designed the show for the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo, and in March it will travel to the Wiels Center for Contemporary Art in Brussels; so stay in Europe. It became difficult to display large works of art in America. We can certainly understand Lutz Bacher as a leading American artist.

Small changes are very important

Bingo is a part of everyday American life and is a very social game. But in Bacher’s artwork “Bingo (Or the Year I Was Born),” the board is thrown backwards. The numbers shone soundlessly and without resonance into infinity. Bacher discovered the machine (or specifically sought it out) and declared it a work of art. He appropriated it, as the art world would say. The changes are small but important.

Typically you don’t see controls connecting a random generator to a bingo scoreboard; here the circuit is behind plexiglass. So you can see what produces the numbers, but it doesn’t change the attractiveness of the opportunity. In the bright, concrete and glass halls of the museum, people subconsciously began to make silent predictions – would the next prediction be a double-digit, even number, far from the previous number? And you think about how many things are unpredictable in life, how much people depend on chance and luck.

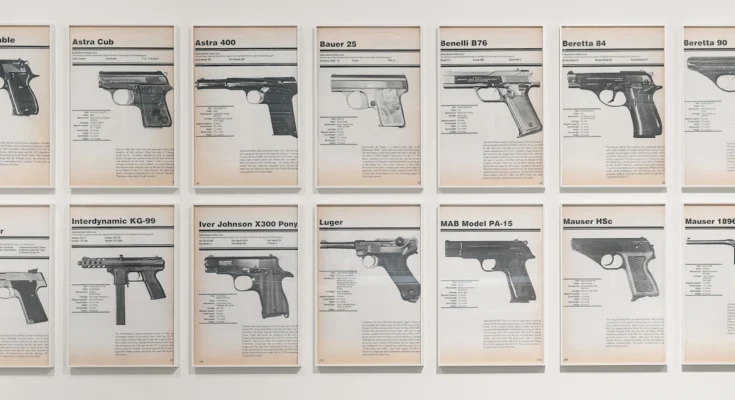

Not far from the equipment are two male dolls that have clearly been sorted out long ago and now form a boring gay dream couple (“Boyfriends”, 2006). Opposite him, an entire wall was covered in enlarged pages from handbooks on firearm repair and maintenance. 2019’s Firearms was his final work, completed the day before he suffered a heart attack and died. Then there are the large Levi’s jeans filled with Styrofoam balls.

Guns, sex, gambling, fate, big bodies, freedom and death, even a transcript of Lee Harvey Oswald’s interrogation appears. Lutz Bacher’s work is full of Americana. These are not the highly polished surfaces of Jeff Koons, but rather touching artifacts found in rural thrift stores. This is a dark place, not a bright place.

The artist, whose last name is Bacher, most recently lived in Berkeley, California. She was married to an astrophysicist named Donald C. Backer – hence the pseudonym. His first work was created fifty years ago, in 1975. He initially devoted himself to photography, exhibited in New York, but rejected the use of any biography by the art world; Only towards the end of his life did important exhibitions accumulate.

“The Year I Was Born” is an expanded title of “Bingo.” Is your birth year some kind of lottery number? Or does this refer to the scoreboard, which may date to 1943, the year the artist was born? People think of the game of Bingo, which is very American and… working class is the little people’s roulette. All attached to equipment made of steel, aluminum, light bulbs and plastic, all the streaks of destiny and hope that play a role in many American films and determine the course of this great country.

Lutz Bacher: “There is no stopping, there is no turning back”

Bacher never explains things to the end; they blow you up when you stand in front of them. He consistently rejects the wholesale self-disclosure that characterizes much of today’s art (where you come from, what influences you, which films or novels draw on the strokes of the brush). Even the authorship itself is in doubt – there is no consistent handwriting in the work, no signature. “Their method,” wrote the art magazine “ArtReview,” “is to constantly change form, rejecting their own signature and evaporating like smoke.”

Perhaps this is why Bacher was drawn to characters who are also refugees. A series of pictures taken by paparazzo Ron Galella show Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Galella ambushed him in New York, where he walked through a park in jeans and a T-shirt. Bacher reproduced the photos and comments in the 1989 piece “Jackie & Me.” Paparazzo interpreted Jackie’s behavior as a game — she alerted Secret Service agents, then ran away and deliberately allowed herself to be followed, he claims. “Jackie Kennedy Onassis, the most desirable woman in the world, wanted to be pursued by me – by me, Ron Galella, the paparazzo. It was clear to me that there was no stopping, no turning back.”

Everything is a narrative that frames reality. All that remains are shadows, blurry photocopies, feelings of paranoia. The great thing is: you don’t need to know anything about Lutz Bacher to appreciate his art. His works are full of enigmas, but have a psychology that is both dense and open. In the smaller hall there is a figure in the form of a bison, which was also taken over by Bacher (“Bison”, 2012). It is not known what their purpose was in doing this. On a frame of wooden slats and chicken wire, the head and shoulders were sculpted with papier-mâché and then painted. They are too incomplete for a film prop and too illustrative for a work of avant-garde art from the 20th century.

Precisely because their purpose is not known for certain, they are seen as evidence of a particular era and culture. We think about Western films, about target practice, and about the curiosity that America generated as a self-made, autodidactic nation without a centralized cultural center. “Men at War” from 1975 features black-and-white photographs of soldiers, half-naked in the sunlight, in the eternal state of waiting that accompanies war and is what gives the exhibition its title: “Burning the Days.”

Is this a critique of war, of masculinity? And why is one of these skinny boys wearing a swastika on his arm and a sailor’s hat? Are they martial enough to be considered warrior symbols? When Bacher created his “Men at War” photo series in the mid-1970s, his gender was unknown to the public. It’s not at all clear that there’s a woman hiding behind it. This is a different form of play than the gender-switching play that takes place in public; Her identity as a woman was not denied, she was only misled.

Everything is fragile, everything is visible from the side, as you pass by, so to speak. The fact that Bacher always chooses existing objects from the fabric of the world does not make the matter arbitrary. He had a famous pin-up painter paint Eisenhower’s curvaceous, perfect American beauty for him again, and he acquired a film print of Disney’s “Snow White,” which now stands on the concrete floor in a tin with an address label like a find from a lost world. The sound of an electric organ sounded throughout the room, as if it penetrated the room and used the computer to operate the lock.

“Burning the Days” is the first posthumous retrospective of the influential ghost – and an exhibition that sets the standard for quiet precision.

“Lutz Bacher. Burning the Days”, until 4 January 2026, Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo