EL PAÍS openly proposes the América Futura column for its daily and global informative contribution on sustainable development. If you want to support our journalism, subscribe Here.

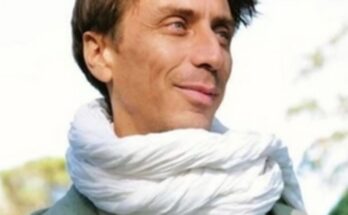

Edgar Parra is a fan of magic. He likes simple tricks: pulling an infinity scarf out of his sleeve, turning a wand into flowers, sowing a seed and watching a plant sprout. “Nature creates the greatest magic,” he says from the Orchid Courtyard of the Royal Botanical Garden of Colombia, a community and self-managed project he founded and directs. “One day I go to rest and the next day I find flowers,” he says smiling, dressed in a T-shirt printed with butterflies. Located in the Lucero Medio neighborhood of the city of Ciudad Bolívar, at the southern tip of Bogotá, the garden’s very existence is almost magical.

“We would never have imagined a place like this, in the middle of the neighborhood, in the middle of the concrete. It’s something strange, very beautiful,” says José Andrés Celis, a visitor from a nearby town. To enter is to go from concrete, cars and cables hanging over the road, to crashing into a tangle of plants, leaves and fruit. Orange flowers hang from the the poet’s eye (Thunbergia alata), as well as purple and reddish bougainvillea (Bougainvillea glabra). THE the old man’s beard (Tillandsia usneoides) spreads together with the currubas on its vine (Tripartite passion flower). On the ground, species of intense green ferns and thorny bromeliads.

All this in a city that concentrates 8.5% of the almost eight million people who live in Bogotá, and where 98% of its population lives in the quarter of the territory that is urban, according to data from the Mayor’s Office. A city where there are just 3.2 square meters of parks and green areas per inhabitant, well below the 15 required by law and the neighborhood average, 4.6 square metres. “In the midst of all this, we found this place that preserves nature,” adds Darwin Supelano, who accompanies Celis on her visit. “This is admirable.”

Recover the ordinary

Four years ago Parra, an architect by profession, opened the botanical garden where the Gimnasio Real de Colombia school, which he also directed, previously operated. “We always tried to make sure there was a lot of greenery: we put shades in every little corner,” he recalls. When the school closed, the space itself showed them the way: “We had a huge green area in the middle of the neighborhood. It was obvious that we had to make a garden.”

He never wanted a “kept and organized space, like an English garden”. He preferred to imitate the mountains: “abrupt, ordinary environments that no one combs”. In this way, he says, they are “more beautiful” and more “alive”. While rummaging through the vines looking for caterpillars, Parra assures himself that he is a “defender of the ordinary”. He likes the essential and unpretentious, “the pure”. And his garden is like this. Some visitors ask him to collect fallen leaves and cut stubble and weeds, “but I want this to stay.”

Today, the Royal Botanical Garden of Colombia has 600 species, mostly native, distributed in six spaces: the Insect Museum, the Orchid Courtyard, the Bromeliad Garden, the Butterfly Labyrinth, the Succulent Terrace and the Aquarium Tunnel. It also has a natural pool fed by a spring from the Tunjuelo river basin, a tributary of the Bogotá, and whose origin is the Páramo de Sumapaz, the largest in the world.

On the shore, three children eat biscuits and sunbathe after a dip. “We come almost every Sunday,” said Dylan Castiblanco, 11. “We like it a lot because there is a lot of nature,” he adds without finishing chewing. Santiago Duarte, 13, who has water dripping from his forehead, intervenes: “I like cold water,” he says. “And nature, because it gives life to things.” They live a few blocks away and come with family, friends and sometimes alone. “Or birthdays,” adds Castiblanco. “The atmosphere is cool, calm. Better here than other places in the neighborhood,” says Edison Gamboa, 15, as he plays with water.

Resignifying the territory

Parra, born and raised in Ciudad Bolívar, knows that the city carries a great stigma of violence and poverty. “I love my city, but there are things that perpetuate violence,” he says. According to the mayor’s office, almost half of the population lives in vulnerable conditions, one third in moderate poverty and one in ten in extreme poverty. In 2024, 236 murders, 4,796 robberies against people, 917 sexual crimes and 129 cases of extortion were committed. It is a territory with multiple challenges and complexities that create an environment of vulnerability for its inhabitants, “but it’s not just that,” he insists. “The garden is proof of this.”

A few minutes ago Sara Alfonso, one of the guides, concluded a tour with the visitors. Camminando assures that the space “bets a lot on the resignification of the territory”. It is a community, neighborhood, family commitment that generates a sense of belonging and pride among neighbors. “People’s faces change after the tour,” he says, smiling. A biology student, he assures that it is more relevant to “talk about the territory, the history of this place, how it was born and the relationship that each person has with it”, than giving technical explanations about plants.

Parra adds that, just by explaining the origin of the cenote water, visitors “get to know their territory better and discover that Ciudad Bolívar is also rich.” Let us remember that the Páramo del Sumapaz, south of Bogotá, is a fundamental ecosystem for the entire world. “This changes the idea that wealth is only in the north (where the richest neighborhoods of the city are located). We also have ours in the south,” he emphasizes.

A pedagogical jewel

All this, Alfonso expresses, allows us to “awaken the sensitivity of the love for nature and for life”, something that the teachers who visit the garden with their students take advantage of.

Alix Vargas, a financial education teacher at the Montreal City School adjacent to the garden, often accompanies her students. There he teaches, together with Parra, how to save and take care of resources. “We talked about how succulents save water in times of drought,” he says, “but also about the importance of non-monetary resources, like water and sunlight.” In this way it sows territorial roots and passion for nature and awakens an urgency to preserve it that is not limited to the classroom. “They take everything home,” says Vargas: they reuse water, collect rain, recycle plastic.

Although he was never a student of Vargas, Santiago Parra, Edgar’s nephew who works as a guide in the garden, also learned to love the plants there. They used to generate little interest and now he talks to them every time he waters them. He wears a cap backwards and laughs when he admits it, but confesses: “I tell them they have to look good for visitors, so that people see them and are surprised.” Far from being a one-sided dialogue, Santiago assures that they will understand him and respond to him. “I water them and take care of them, and they always give me back a fruit or a pleasant smell.”

For Edgar and his entire team the garden is full of magic. More than an illusion, they see in it and the place “an example of how we can pull wonderful solutions out of the hat,” he says. “We hope to continue to create so much magic in the garden,” he concludes.