Last week, during a short trip to Guatemala, I met the journalist José Rubén Zamora in a cell of the Mariscal Zavala prison, where he remains locked up, unjustly detained for more than three years. He is a prisoner of conscience. He is a man without self-defense. His trial does not have the slightest guarantees, but he ages in that cell with concrete walls and iron doors with only a small window crossed by bars, where he recently turned 69.

A year ago I went to visit him at home, during a very short exchange of prison with house arrest that lasted just a month.

That day we hugged each other, we laughed, we celebrated while sitting at his table and not on the cold concrete of the prison floor. He told me about his torments. He was tortured by the jailers of the penitentiary system – then still under the administration of President Alejandro Giammattei, who was particularly affected by the accusations of palace corruption published by José Rubén –.

He showed me his arm and told me he had bugs in his body. One night, a guard slipped a bag under his cell door with “hundreds of insects that I had never seen in my life and that breed like rabbits,” he told me. “A horrible spider had woven a thread through which it came down every night right above my head. I opened my eyes and saw it and could no longer close them. Two days later there were hundreds of little spiders. I managed to get a Baygon but it was like Martini for the insects, which attacked with greater force.” He obtained an industrial insecticide that eventually eliminated the visitors, but left permanent scars on his nervous system.

José Rubén Zamora returned to the same cell. The new government of Bernardo Arévalo cannot free him, because this depends on a judicial system hijacked by powerful figures who benefit from corruption and impunity. But he was able to improve his condition. Now he has a bookshelf with books and a coffee pot and a small refrigerator and no one knocks on his door at night anymore or keeps the light on or turns off his water. Nor does he throw a lot of live insects at him.

He keeps his sense of humor intact. I brought him a book by Filipino journalist Patricia Evangelista on Duterte’s repressive campaign and when he saw it he said: “It’s a good thing you didn’t bring me shampoobecause I have enough for three life sentences.” Evidently I am more optimistic than some of your friends, because my gift is just over 300 pages, unlike the copies of Les Misérables, Crime and Punishment AND Moby Dick which took up half a shelf.

Outside his cell, in a 2.5-metre corridor, he walks back and forth every day until he completes, by his count, 12 kilometres. Despite his efforts to stay fit, his physical deterioration is notable, natural at his age but aggravated by his years in prison.

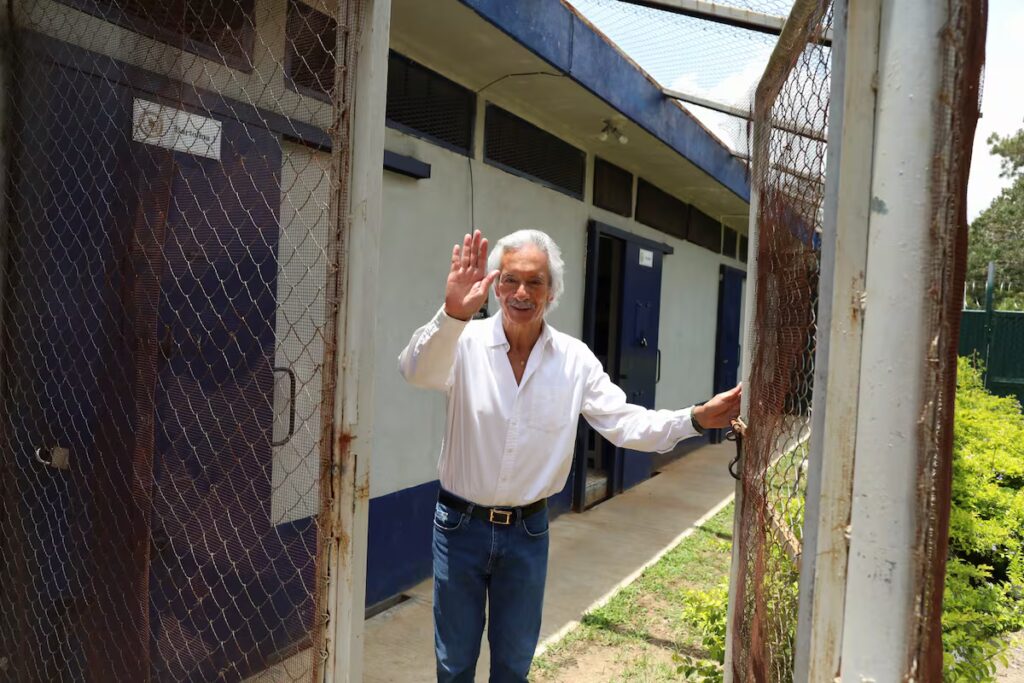

After a really pleasant hour we said goodbye with a hug and a guard opened the door for me. I went out. I turned and saw him still with his hand raised, smiling at me. At that moment, all the injustice of which José Rubén is a victim suddenly invaded me. I went down the street or to the sea or to the mountains to listen to the wind and my friend stayed there. He can’t go out.

An abyss separated us now. Precise like the short but insurmountable distance between the cell and the forest surrounding the prison. Deep like a wound in the world.

I couldn’t stop thinking about it

Two days later I met in Antigua Dr. Homero de León, a Mexican, member of the Doctors Without Borders team that only two weeks earlier had been treating patients in Gaza under indiscriminate Israeli bombing. He spent six months there, in three shifts of two months each.

He told me about the lack of medical supplies to perform simple procedures; dilemmas to decide on whom to apply the little anesthesia or antibiotics they have available. From the Israeli ban on introducing toys because they consider them to be of potential military use (?)… From the commitment of the entire hospital to restore a bit of normality to the children; of temporary orphanages to accommodate thousands of orphans.

He told me about the difficulties that the medical staff in Gaza are going through: nurses and doctors displaced again and again – the hospital director had to move twelve times in two years -, with tents loaded on their backs because their houses are rubble; who have lost dozens of relatives, who have no food but carry indelible trauma. She told me about a nurse who, as soon as she arrives at her tent, sits in a corner crying because she can’t do anything but wait for the moment to go back to the hospital to distract herself. From another colleague who, during a short break, told him that he had lost 14 members of his family in a bombing. In a recent bombing. The intense work in the hospital helped him not to think about it all day. “When their shifts end, our colleagues return to their tents where they have no latrines or drinking water. In which are what remains of their families. The next day they are in the hospital working tirelessly. They have killed 14 Doctors Without Borders colleagues. In total, more than 1,700 health workers have lost their lives,” he told me.

In Gaza there is a beautiful sea but it is not possible to contemplate it. The roar of the waves is lost in the terrible noise of Israeli drones, Israeli planes, Israeli tanks, Israeli bombs that have destroyed everything.

In every departure from Gaza, in every farewell to his Palestinian colleagues, Homero de León also experienced the revelatory moment that I experienced two days earlier in Mariscal Zavala’s prison. He leaves. They remain. The opening of an abyss. “It’s just this feeling. Exactly,” he told me, “I always feel a little guilty.” The naked injustice, evident in that moment. The abyss that separates, precise and dark like the distance between Gaza and Jordan. Deep like a wound in the world that reveals itself, painful and full, in that precise moment.