The obituaries of journalist Lluís Permanyer, who died last October, contained a revealing piece of information. Despite his notoriety, there would have been no funeral or public burial: the man who was one of Barcelona’s most important chroniclers had donated his body to science. Neither neoclassical pantheon nor tombstone with the plot of the Eixample: the last service to curiosity that emerges from his career will be on a dissecting table.

Only the three largest Catalan universities together require almost 300 institutions every year to carry out their training activities. Not just those for future doctors; Those enrolled in nursing, speech therapy, biomedical engineering and physiotherapy courses also require training in anatomy. As with almost all Barcelona-related topics, Permanyer had also written about dissections. Now the object of study will be the anatomy of the reporter.

It was the subject of one of his articles in The avant-garde the meeting of Barcelona in the 1920s with the medieval morgue of the Santa Creu hospital. The expert journalist recalled, in October 2024, how for 500 years most of the mortal remains of poor and familyless patients have been study material for professors and students. The remains ended up in a mass grave, the run themlocated where the fountain of the Doctor Fleming Gardens now stands, in the Raval.

Half a millennium of science led to the shock of citizens almost a century ago. The transfer of the hospital to the new modernist site of Sant Pau, inaugurated in 1930, condemned the mass grave, which on paper did not work after the royal veto of 1775. While waiting to transfer the morgue, it was decided to pile up the remains and wall them up. The fall of the wall, during the construction of the Library of Catalonia, brought to light thousands of walled-in skulls and, Permanyer explained, the image was so impressive that a moved Picasso wanted to exorcise it with the dead Dona.

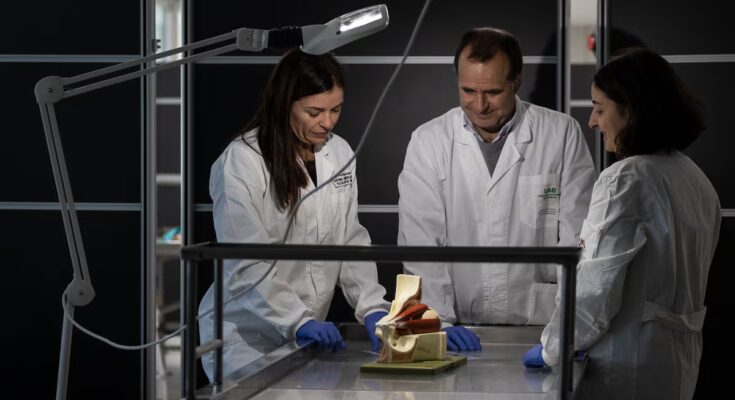

Like the reporter, Dr. Santiago Rojas has decided that his last lesson will be in the form of an anatomical piece. He is in charge of the Dissection Room of the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), where students, researchers and surgeons pass by trying to practice procedures. “My first warning is that you have to treat the pieces with respect. They were people and they are delicate. But that’s why they shouldn’t stop touching everything they need. This is not a museum,” he explains.

UAB alone requires up to 70 organizations each year to meet its needs. The donor register has been closed for 10 years and has 4,000 registered donors. At the other end of the list is Pompeu Fabra, with only 250 volunteers and still receiving applications. Its share is 16 deaths. Permanyer and his wife, family sources explain, had chosen many years ago for their bodies to end up at the University of Barcelona (UB). It is the one that requires the most, given that it has two locations: 200 in total. Alberto Prats, professor at the Faculty of Medicine of that center explains that 13 thousand volunteers are registered there, but it is estimated that there are around 8 thousand actual volunteers. “Sometimes the family objects at the last minute or didn’t know they were a donor,” he explains.

Willingness to donate is not enough. Rojas explains that they cannot accept victims of violent deaths or those who have donated organs. They are needed intact. The law also prevents the use of remains of people infected with HIV or hepatitis types B and C, which is certified with a test taken from the corpse. Obese people are also rejected, as excess fat makes the process difficult. “The main reason for donating is altruism, but many tell us that they also do it so as not to burden their families”, adds Prats, who assures us that those who register are usually elderly.

Permanyer loved telling stories and will do so until the last moment. At UAB, a leg or torso can be examined by 18 groups of students, for two hours each, Rojas explains. But even in pieces, a corpse explains many things, he adds, showing the lesion that a stroke leaves on a beige brain, the effect of the liquid that prepares the corpses and guarantees their preservation. They are marked to ensure traceability and once their useful life is over they are incinerated. “When the institutional change occurred in the country, it seemed to me that I would be more useful in the newspaper as a reporter from Barcelona than reporting on Vietnam,” the journalist said in 1988 to explain his move from the international to the local section. Nearly 37 years later, in the great passage of existence, its usefulness reaches the dissecting table.